© 2024 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

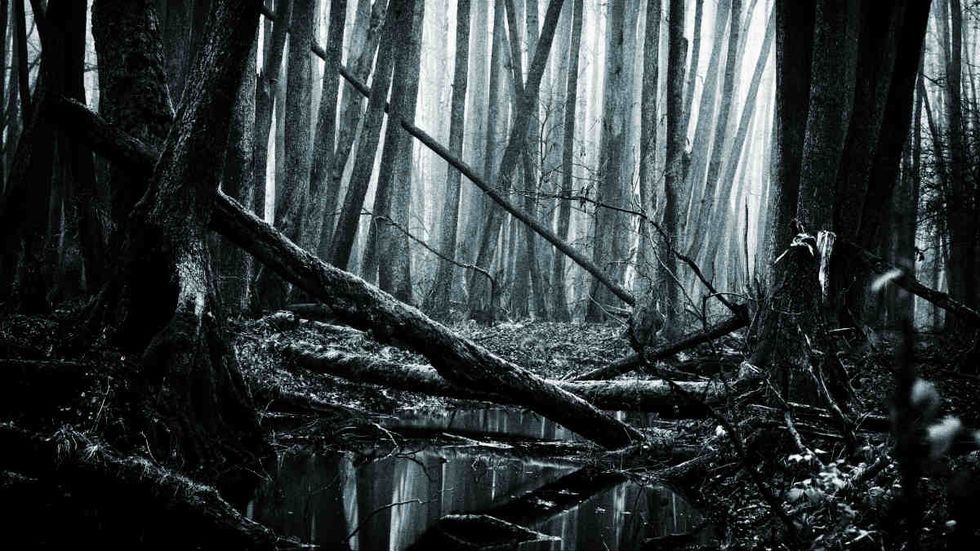

We’re still dealing with shockwaves of President Trump’s decision to remove James Comey, a no-brainer decision that took too long. Many of Trump’s supporters were more than happy to see some swamp drainage in the form of a firing that should have happened multiple times already. But there are many more to go.

As CR’s Daniel Horowitz pointed out, post-Comey canning, the question remains as to why there haven’t been more and why Comey shouldn’t be the first in a line of long-delayed firings of the Obama holdovers within the federal government who started their preparation to block this administration long before Trump raised his right hand in January.

The real question isn’t why Comey was shown the door, but why voters have not seen the flurry of pink slips that one immediately imagines when Trump ran on promises to combat the entrenched Washington establishment (read: drain the swamp) and “deconstruction of the administrative state?”

As it turns out, despite a shared desire among many conservatives, populists, and other camps to exile more swamp monsters – Internal Revenue Service commissioner John Koskinen’s name immediately comes to mind – the terrain protecting them is far murkier than one might think, and the permanent government inside the D.C. beltway is incredibly well insulated on a number of fronts.

Civil service laws

First, the regulations around federal employees are almost impossible to navigate. Last year, Kathryn Watson wrote a piece for the Daily Caller outlining that your average person working at a federal job is far more likely to be arrested for drunk driving or audited by the IRS than to be terminated for poor performance or slacking off at work. Meanwhile, private sector workers face an average rate of termination for poor performance that’s almost 650 percent higher. Let that sink in.

The reason for this seemed like a good enough idea at the time. Prior to our current incarnation of the civil service system – which differentiates political office-holders from career employees – everything in the executive branch was run on the “spoils system” of old, where everything was a political appointment.

Progressive era civil service reform sought to correct that – and initially did – but it proved to be an over-correction in many respects. Now it’s nearly impossible to fire most federal employees because increased employment protections have removed almost all accountability. Now, even watching porn on the clock isn’t really a firing offense, according to a 2015 story at CBS.

What these changes really did was simply trade the vice of political patronage for the prospect of an entrenched administrative government. “At least under the spoils system,” wrote Ed Morrisey at Hot Air in 2015, “voters could hold the majority party accountable for bad behavior by putting another party in charge and have them clear out the deadwood. These days, the deadwood get to stick around for years while watching porn on taxpayer time.”

The 4th branch of government

Then you have the fourth branch of government: boards and commissions set up to be independent of political shockwaves and therefore act as unconstitutional institutions operating completely untethered to the will of the American people.

As we pointed out in December:

Rather than being independent and “above” politics, these commissions are largely unaccountable to the American people, and soak up powers and responsibilities from the branches of government that actually are.

Right now, one such agency is fighting in the federal court system to keep itself protected from executive oversight. The Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB) – an Obama-era creation – is currently embroiled in a lawsuit about whether or not its head can be fired by the president without cause.

Now the DOJ has even joined in by filing an amicus brief against the CFPB, arguing that the president’s removal authority as outlined in the case “Humphrey’s Executor” clearly gives POTUS the power to hand a pink slip to agency heads as he sees fit.

One would naturally assume that the authority vested in of the president would give him the power to fire people for any reason, or even no reason at all, but such is the problem when you create governing bodies designed to completely obfuscate the will of the electorate.

Protection from the courts

Congress is ultimately the arbiter of the terms of federal employment and what offices exist by its control of the federal purse, but not if the federal courts have anything to say about it.

Earlier this week, a federal court struck down congressional efforts to streamline the removal process of workers from the Department of Veterans Affairs and overturned the termination of Phoenix VA hospital director Sharon Helman, arguing that her case has to go before the U.S. Merit Systems protection board. The ruling also got rid of a provision in the Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act that allowed for an expedited firing process of VA employees for incompetence or bad behavior.

In a more recent column at CR, Horowitz takes a deep dive into this issue and points out that the case – as with so many others – goes back to the sovereignty problem created by a runaway judiciary:

Even Congress has no power to force particular executive staff upon the president. Now the federal courts are essentially giving corrupt employees extra bites at the apple to keep their jobs … even when Congress explicitly agreed with the administration’s decision to terminate the bureaucrat.

“But Congress cannot force upon the president any particular personnel he doesn’t want to keep,” Horowitz adds, pointing to judicial reform as the necessary remedy to this problem. “There is no fourth branch of government that can be created by Congress, operating autonomously within the executive branch and not subject to the president’s power to fire. As James Madison said, ‘[I]f any power whatsoever is in its nature Executive, it is the power of appointing, overseeing, and controlling those who execute the laws.’”

Clearly, the executive power vested in the president of the United States would include the power to make decisions about personnel, full stop. That power, however, has been stymied and usurped by progressive-era legislation and left-leaning judicial rulings for decades. If Trump wants to hold firm to his recently reiterated commitment to continue draining this swamp, he and his legislative allies will need open eyes about just how deep, sticky, and drainage-resistant the metaphorical muck truly is.

Want to leave a tip?

We answer to you. Help keep our content free of advertisers and big tech censorship by leaving a tip today.

Want to join the conversation?

Already a subscriber?

Nate Madden

Nate is a former Congressional Correspondent at Blaze Media. Follow him on Twitter @NateOnTheHill.

more stories

Sign up for the Blaze newsletter

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree to receive content that may sometimes include advertisements. You may opt out at any time.

© 2024 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

Get the stories that matter most delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree to receive content that may sometimes include advertisements. You may opt out at any time.