© 2024 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

You want to take politics out of the judicial confirmation process? Take politics out of the federal courts.

It’s that time of the decade again. Another massive partisan fight over a Supreme Court nominee is about to ensue. While everyone debates the minutia of the nominee’s record, few will bother reflecting on the fact that Supreme Court nomination fights have only become acrimonious because the role of the federal judiciary has been expanded to that of a king.

One could get a glimpse of the original design of the court by reading a letter John Jay wrote to President Adams rejecting the president’s request to name him chief justice of the Supreme Court. Jay, who had been a member of the very first Supreme Court, lamented how boring and inconsequential the court was to molding the direction of the country. He complained about the judiciary not being on equal footing with the other branches of government.[1] And being the political statesman type, Jay had no interest in languishing in a stuffy room adjudicating criminal cases or bankruptcy law with the waning health of his elder years.

Contrast that to the spectacle of this announcement of Neil Gorsuch for associate justice and both sides are waiting with baited breath as if the future of our entire society hangs in the balance. It wasn’t always this way and it doesn’t have to be this way.

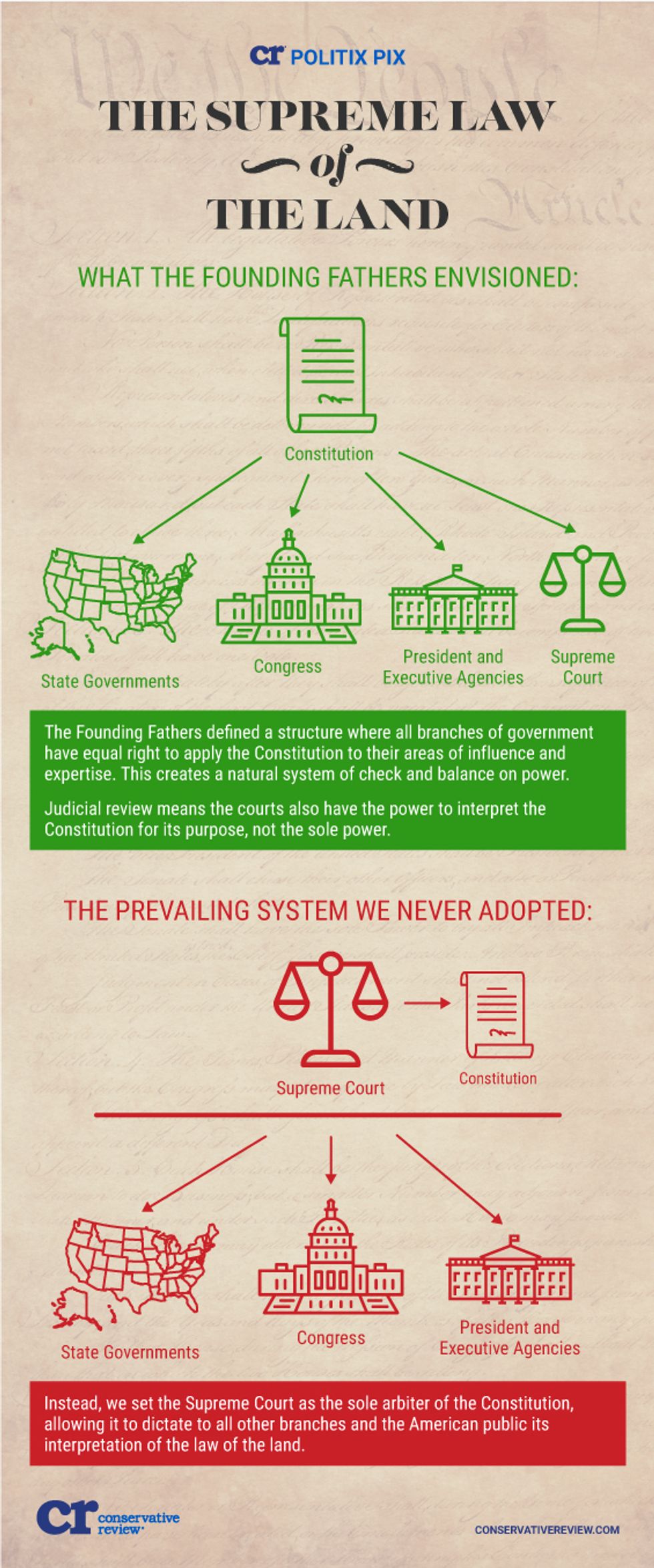

Judicial review never equaled judicial supremacy

The federal judiciary was conceived as the weakest branch of the federal government. The legislature — the elected branch with the most transparency (through public votes) — was given the “predominant” power to legislate and fund the functions of the federal government born out of the “few and defined” enumerated powers. [2] The executive branch was to faithfully execute those laws and was given the power to sign or veto new legislation. The judiciary, which was to be comparatively the weakest branch and wield “neither force nor will”[3] over the direction of the country, was to interpret the application of those laws in individual cases and controversies. Everything else belonged to the states.

Even when John Marshall popularized the concept of judicial review in Marbury — that justices can look at the constitutionality of a law in addition to interpreting it and are obligated to block its implementation when it violates the Constitution — he never envisioned the judiciary as the sole and final arbiter. He meant that even the weak judiciary, which is unelected, has no funding or enforcement mechanism, and has no ability to make a decision without first receiving a case or controversy with legitimate standing. Similarly, it also had the obligation to follow its oath of office to the supreme law of the land — the Constitution.

But certainly, members of the other branches of the federal and state governments — which swear the same oath and wield much more power — must adhere to the Constitution. And it was quite clear that if the courts ever delivered a revolutionary opinion in a specific case, the other branches would not implement it as precedent. For example, if a court redefined marriage and sexuality and threatened to throw someone in jail for not servicing it, the other branches would refuse to execute the bench warrant or defund such enforcement. There would be a controversy and ultimately the issue would go back and forth with popular opinion and elections. There is no finality of judgement (res judicata) with constitutional questions and political/social issues the way there is with judgements in individual civil and criminal cases.

Moreover, even the concurrent jurisdiction (not exclusive jurisdiction) over constitutional interpretation was only meant to be exercised in “some” individual controversies, not be signaled as precedents for broad social and political issues. [4] Remember, Marbury, the source of judicial review, was the most inconsequential, isolated, “inside baseball” case imaginable that had no bearings on the future social fabric or ability of one party to win elections over the other.

Finally, judicial review was only accepted as a means of adhering to the Constitution, not redefining it. The law had to manifestly violate the plain meaning of the Constitution as adopted. Anything less, would not warrant judicial intervention. [5] As the great James Wilson, one of the crafters of Article III and one of the original Supreme Court justices, said, “"[l]aws may be unjust, may be unwise, may be dangerous, may be destructive; and yet not be so unconstitutional as to justify the judges in refusing to give them effect.” [6]

Courts crown themselves king of the republic

This all changed during the Warren-era in the 1950s. As the Congressional Research Service observes in a brand new report on Congress and constitutional interpretation:

In the mid-20th century, however, the Supreme Court began articulating a theory of judicial supremacy, wherein the Court no longer shared its role in interpreting the Constitution with the other branches of the federal government, but rather characterized its role as being the preeminent arbiter of the Constitution’s meaning. For example, in Cooper v. Aaron, the Court read Marbury as “declaring the basic principle that the federal judiciary is supreme in the exposition of the law of the Constitution, and [this] principle has ever since been respected by this Court and the Country as a permanent and indispensable feature of our constitutional system.

There you have it. Around the same time the courts began to rewrite the Constitution, they expediently crowned themselves the sole and final arbiter of any constitutional interpretation. Madison directly rejected this notion when he wrote in Federalist #49: “The several departments being perfectly co-ordinate by the terms of their common commission, neither of them, it is evident, can pretend to an exclusive or superior right of settling the boundaries between their respective powers.”

Oh, and by the way, federal judges are unelected, serve life tenures, and have bound future courts to their “precedent.” And it’s not just the Supreme Court. Any puny district judge, can declare a boy a girl and force states to obey or even issue national injunctions against long-standing policies. Any activist judge within the Ninth Circuit can overturn 200 years of settled sovereignty law and put a stay on immigration enforcement. They are never bound by real precedent.

Consequently, we are left with the following judicial equation: Judicial supremacy/exclusivity + one directional stare decisis + unelected life tenures + living and breathing Constitution = a tyranny King George himself never envisioned.

With this in mind, is it any wonder why both sides want to get ideological allies on the courts?

A grand bargain to save the judiciary

On the other hand, now that judicial review has morphed into judicial supremacy — in conjunction with the irremediably broken conception of the Constitution itself among the legal profession and those bringing most of the lawsuits [7] — there is no way judicial review will ever work for our Republic without turning into a judicial oligarchy, especially because federal judges serve life tenure.

Congress, the Justice Department, and each state needs to have its own office of constitutional interpretation. After all, they all swear oaths to uphold the Constitution. This would mean that federal courts would not have the authority to adjudicate cases to overturn laws the Left doesn’t like, such as marriage, religious liberty, abortion regulations, immigration laws, and voter integrity laws. Likewise, federal courts would not have the authority to strike down overzealous labor, environmental, and campaign finance regulations. Those cases would be rerouted to state courts, which are generally elected. It would foster federalism, make state judicial elections great again, and tailor society more toward the character of each locality. On net, conservatives would be dumb not to take this deal. For every victory we win in the court today, we lose 10 others of greater magnitude. Plus, most of our victories are very narrow and fleeting (just look at Heller on guns and Shelby County on election law), while theirs are broad and eternal.

Such a bargain would remove all the politics from the nomination process and it would restore the trust and prestige to the core purview of the court — applying the statutes as written. It is the painstaking job of fair statutory application for which our founders wanted an independent and unelected judiciary. Leave the politics to the elected branches.

[1] John Jay, The Correspondence and Public Papers of John Jay, ed. Henry P. Johnston, A.M. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1890-93). Vol. 4 (1794-1826). 2/1/2017.

[2] James Madison, Federalist #51 [“In republican government, the legislative authority necessarily predominates.”]

[3] Alexander Hamilton, Federalist #78.

[4] John Marshall, Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 179 (1803). [“In some cases then, the Constitution must be looked into by the judges.”]

[5] While debating the Constitution in 1787, Iredell emphatically declared that a law “should be unconstitutional beyond dispute before it is pronounced such.” Letter from James Iredell to Richard Spaight (Aug. 26, 1787), The Papers of James Iredell, 3:310. Justice Samuel Chase said, “if I ever exercise the jurisdiction [of judicial review], I will not decide any law to be void but in a very clear case” [Calder v. Bull, 3 US 3 Dall. 386, 395 (1798)].

[6] Kermit L. Hall and Mark David Hall, eds., Collected Works of James Wilson, 2 vols. (Indianapolis, Ind.: Liberty Fund Press, 2007) page 121.

[7] Justice Sam Alito: “What it evidences is the deep and perhaps irremediable corruption of our legal culture’s conception of constitutional interpretation.” Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. ___ (2015) (Alito, J., dissenting) (slip. op., at 8)

Want to leave a tip?

We answer to you. Help keep our content free of advertisers and big tech censorship by leaving a tip today.

Want to join the conversation?

Already a subscriber?

Blaze Podcast Host

Daniel Horowitz is the host of “Conservative Review with Daniel Horowitz” and a senior editor for Blaze News.

RMConservative

Daniel Horowitz

Blaze Podcast Host

Daniel Horowitz is the host of “Conservative Review with Daniel Horowitz” and a senior editor for Blaze News. He writes on the most decisive battleground issues of our times, including the theft of American sovereignty through illegal immigration, theft of American liberty through tyranny, and theft of American law and order through criminal justice “reform.”

@RMConservative →more stories

Sign up for the Blaze newsletter

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree to receive content that may sometimes include advertisements. You may opt out at any time.

© 2024 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

Get the stories that matter most delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree to receive content that may sometimes include advertisements. You may opt out at any time.