© 2024 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

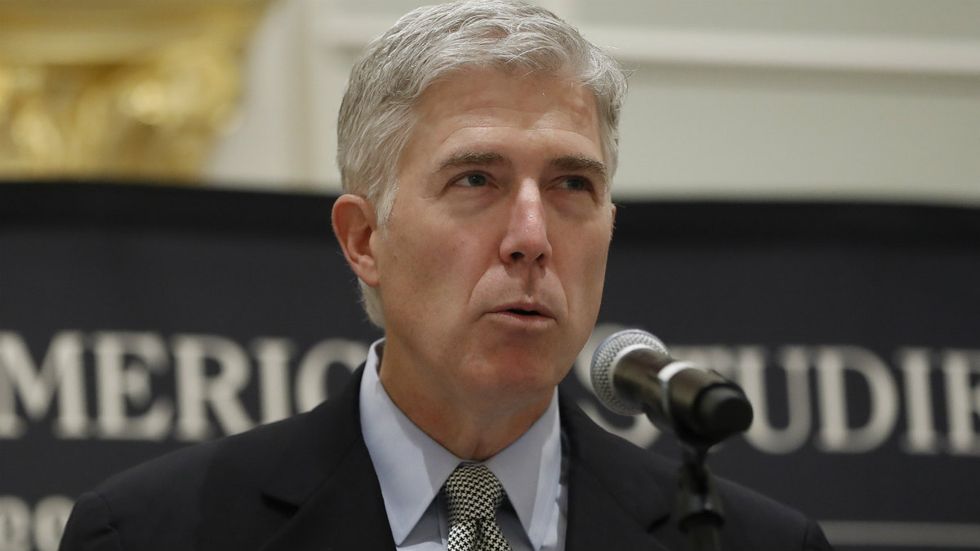

So far, Justice Neil Gorsuch has walked in the footsteps of the late Justice Antonin Scalia, but if yesterday’s oral arguments in an immigration case are any indication, he might be sharply departing from Scalia on national sovereignty and the role of the courts.

Forcing criminal aliens on the American public

America has become a dumping ground for criminal aliens, and now the courts, in a departure from 200 years of settled precedent, are making it hard to deport them on multiple fronts. Regular readers of CR are familiar with the slew of recent cases from the lower courts and the Supreme Court granting new rights to illegal aliens or criminal legal aliens to remain in the country against the decisions of the political branches of government, a phenomenon I referred to in my book as “Stolen Sovereignty.” Unfortunately, it appears that Neil Gorsuch might have caught the disease.

There were a number of disturbing cases of stolen sovereignty last term, in which Kennedy and Roberts joined the Left to invalidate deportations on numerous nuanced grounds. But one case where they held firm was Sessions v. Dimaya. The 4-4 deadlocked case resulted in a rehearing yesterday, now that the court has nine justices. While oral arguments are often not a valid indication of how the justices will rule, Gorsuch’s comments, in conjunction with things he has said in the past about due process for criminal aliens against deportation, raise some concerns. At the risk of angering many conservatives who regard Gorsuch as the greatest accomplishment of this presidency, I’d like to present the concern and why it matters so much.

Since our Founding, and even during colonial times, our government always made it clear it didn’t want criminal aliens. Our political leaders since our Founding understood that a free country will always risk violence from citizens. We are limited in what we can do to prevent every such act. That is why our early leaders made it clear that when it came to immigration, we would absolutely only bring in law-abiding people. This is why Congress has historically given the executive branch broad deference to enforce our sovereignty — our own political right to decide who enters our borders — but not to violate it.

Discretion in deporting criminal aliens

Our statutes require executive officials to deport anyone convicted of “an aggravated felony.” Immigration law defines an aggravated felony very broadly and open-ended, as a “crime of violence.” 18 U.S.C. §16(b) defines a “crime of violence” to include “any … offense that is a felony and that, by its nature, involves a substantial risk that physical force against the person or property of another may be used in course of committing the offense.”

While most conservatives tend not to like broadly written statutes that leave executive officials with broad latitude to regulate the citizenry, immigration policy is different. Clearly, Congress, representing the will of the people, didn’t want criminal aliens in this country. After all, immigration is an elective policy, only for the betterment of the country as a whole. Thus, the default position should be that executive officials have the power to deport any convicted criminal alien unless statute explicitly says otherwise. This is where Neil Gorsuch appeared to side with the Left.

James Garcia Dimaya is a green-card holder from the Philippines who was convicted twice of burglary. Immigration judges concluded that his crimes fit the description of a “crime of violence” and ordered his deportation. The Ninth Circuit, however, applied a broad trend in the court system to invalidate “crime of violence” statutes as “unconstitutionally vague.” The Supreme Court already did this with statutes governing domestic criminals, leading to the re-opening of numerous criminal cases. That was a bad enough foray into a political issue that should be dealt with by Congress, not the courts. But the Ninth Circuit egregiously applied it to criminal aliens, who have no presumptive due process right to remain in the country.

To be clear, immigrants most certainly have due process rights in criminal investigations, but there is no presumptive right to remain in the country at all and prospectively avoid deportation unless executive officials are acting contrary to statute. This is the deference to “plenary power” of the political branches that has been strictly upheld since our Founding.

Gorsuch’s line of questioning

In a lengthy back-and-forth during oral arguments, Gorsuch kept expressing skepticism at Deputy Solicitor General Edwin Kneedler’s argument that the DOJ has broad authority to interpret a crime of violence. He asked how the court would know if the crime likely involves violence. "I would probably want to have statistics and evidentiary hearings and hear experts on that question," Gorsuch said. "And that sounds to me a lot like what a legislative committee might do." He snapped at the solicitor general, asserting, “You're not asking the executive to define these crimes, you're asking us to."

This is simply astounding. Gorsuch is suggesting that the default position is that a criminal alien gets to stay in the country unless the court can determine beyond a shadow of a doubt that the crime is included in statute and that the statute is not “unconstitutionally vague.” He is suggesting that asking the Supreme Court to overturn the activist Ninth Circuit is somehow an act of legislative intervention.

What was most concerning is that Gorsuch conflated deportation with imprisonment — lumping them both together as deprivation of liberty and property. He spoke of a hypothetical person sitting in prison for six months who “wouldn't trade places in the world for someone who is deported” and that the Constitution doesn’t draw a line between regular criminal cases and deportation with regards to the Fifth Amendment.

This ignores an uninterrupted stream of settled case law stating that deportation of aliens is not a punishment similar to domestic criminal punishments that require greater due process, because it is inherent in national sovereignty. I have previously chronicled a list of case law stating that outside of a procedural due process opportunity to present their cases to an administration official, aliens have no right of judicial review to block deportations; most certainly not to invalidate statutes.

Justice Robert Jackson, the great champion of due process and the dissenter in the Korematsu case, said that “due process does not invest any alien with a right to enter the United States, nor confer on those admitted the right to remain against the national will” (Shaughnessy v. Mezei, (1953). Scalia wrote in Zadvydas v. Davis that Mezei was still the precedent and that he found “no constitutional impediment to the discretion Congress gave to the Attorney General,” even for the purpose of detaining a criminal alien in the process of deporting him.

Kneedler properly summed up the argument as follows: “[I]mmigration removal is not a punishment for past conduct. It operates prospectively on the basis of the application of standards adopted by Congress under which an alien is regarded as no longer conducive to the — to welfare.”

Therefore, it’s not the job of the federal judiciary to second-guess immigration statutes or executive authority acting on the power of a statute. Let Congress deal with it if they decide the law is “vague.” But as it relates to immigration power, it’s not vague. It’s a broad license to protect America from undesirable immigrants, much like the ban on immigrants who’ve committed crimes of “moral turpitude,” as Justice Alito observed during the exchange.

The lower courts and Gorsuch’s position

This is even more concerning because of the growing trend in lower courts to “strike down” immigration laws or enforcement of laws based on their novel interpretations of statute. The lower courts are continuing to violate national sovereignty. Last week, a D.C. federal judge limited Trump’s immigration ban as it relates to winners of the diversity visa lottery. Meanwhile, as criminal aliens and illegals get full standing to sue against immigration law, the citizens of California and Judicial Watch were denied standing by the Supreme Court to sue California for violating federal immigration law and using their taxpayer funds for illegal aliens. Are we going to allow lower courts to rule the country?

Applying judicial review and “substantive” due process to criminal aliens on the question of their deportation has no place in the history of our jurisprudence and the plenary power doctrine. Scalia would be appalled at granting such rights to aliens. He was a strong believer in sovereignty and the plenary power doctrine. In his famous Zadvydas v. Davis dissent, he wrote categorically that “Insofar as a claimed legal right to release into this country is concerned, an alien under final order of removal stands on an equal footing with an inadmissible alien at the threshold of entry: He has no such right.”

And yes, Congress has historically granted the executive branch broad latitude to defend sovereignty. As immigration historian Peter H. Schuck wrote in his scholarly book, Citizens, Strangers, and In-Betweens:

Congress has chosen to confer exceedingly broad discretion over the most far-reaching immigration decisions not merely to the executive branch, but to a cabinet official…In the face of broad, express congressional delegations of authority to the president in the area of external relations, judicial power is the most problematic and the President’s authority, in Justice Jackson’s words, “is at its maximum.” There, “[he may] be said to personify the federal sovereignty.”

Yet, once again, today the court is hearing a case, Jennings v. Rodriguez, where the Ninth Circuit has granted illegal aliens a right to bond hearings, even though they are the consummate flight risk. It never ends. Immigration and national sovereignty was the one issue that survived even the onslaught of the Warren Court. Not any more. The courts are now doing to immigration what they did to abortion and marriage. It would be a darn shame for Gorsuch to be the final nail in that coffin.

When considering tampering with immigration policy, Gorsuch should ponder Scalia’s admonition shortly before he passed away, “What Shakespeare is to high school students, a society’s long-established traditions are to the jurist. He does not judge them; he is judged by them.”

Want to leave a tip?

We answer to you. Help keep our content free of advertisers and big tech censorship by leaving a tip today.

Want to join the conversation?

Already a subscriber?

Blaze Podcast Host

Daniel Horowitz is the host of “Conservative Review with Daniel Horowitz” and a senior editor for Blaze News.

RMConservative

more stories

Sign up for the Blaze newsletter

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree to receive content that may sometimes include advertisements. You may opt out at any time.

© 2024 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

Get the stories that matter most delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree to receive content that may sometimes include advertisements. You may opt out at any time.