Blaze News original: Understanding hell — Part III

Hell has long had a hold on the Western imagination.

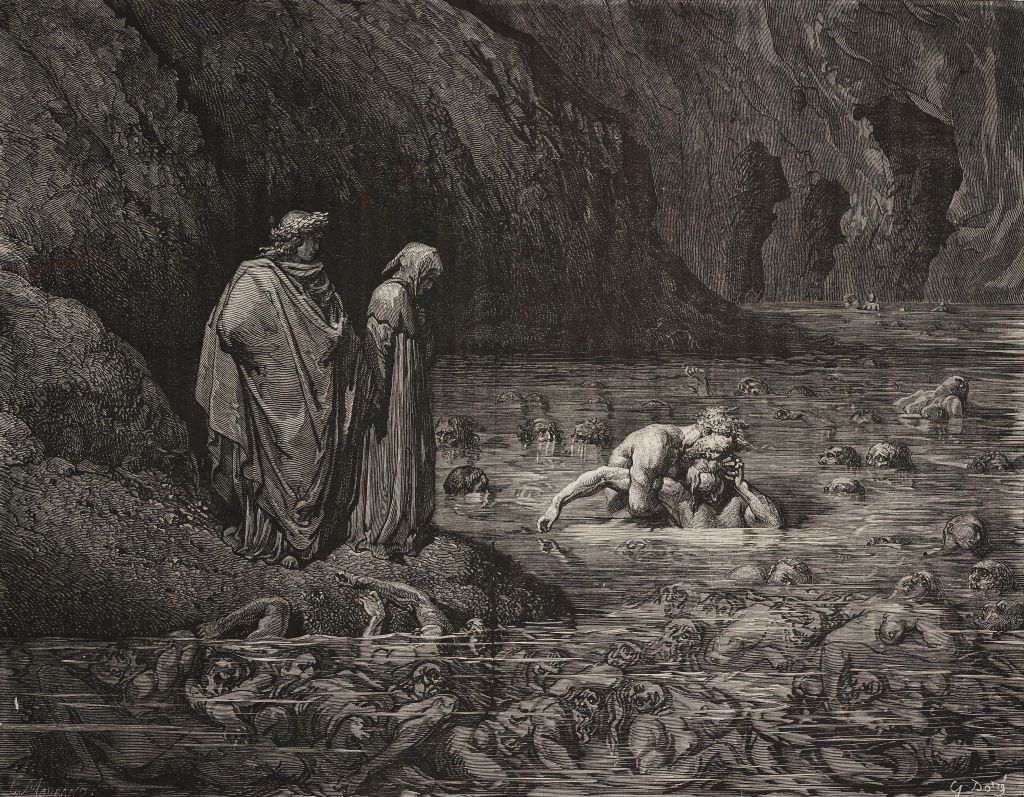

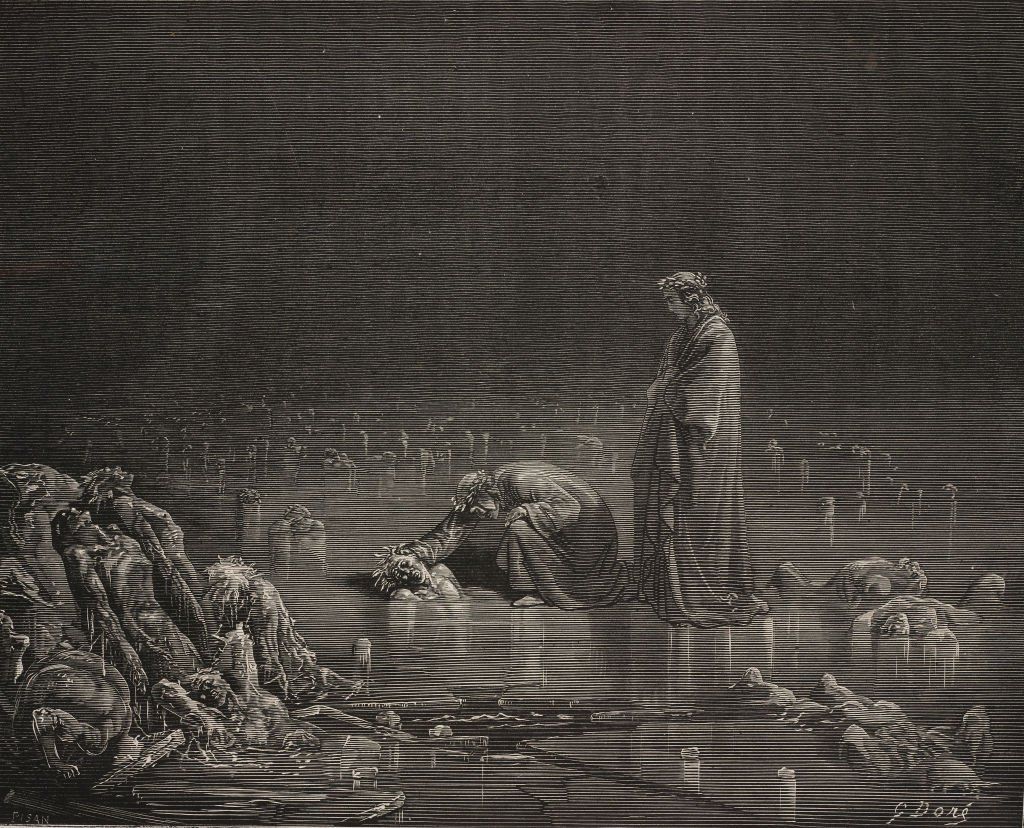

Middle Age scribes rendered depictions of hell strikingly similar both to those painted centuries later by Renaissance greats and to those photoshopped nearly a millennium later by keyboard-bound game designers. It has served as an unnerving backdrop in Hollywood features, medieval passion plays, early modern poetry, and graphic novels alike.

Despite hell's sustained cultural influence, its hold has slipped in the way of belief among Americans. Meanwhile, others, religious and secular alike, maintain that it is a thing of cruel fantasy or, alternatively, a kindness misunderstood.

In Parts I and II, a number of faith leaders and scholars shared with Blaze News their views on hell. These perspectives ranged from the Roman Catholic belief that hell is a place of eternal torment inhabited by those resistive to God's love and grace, to a Jewish perspective that hell is a kind of "spiritual washing machine" that prepares most souls for paradise.

In what follows are two contrastive views on the matter: the first from a conservative Presbyterian who believes there indeed exists a place of eternal punishment for the wicked after death, and the second from a progressive liberal who does not believe in hell but maintains that the truly wicked run the risk of being forgotten or possibly stricken from existence.

While they each have emphasized different consequences in and beyond the land of the living, both individuals noted the importance of taking action in the here and now.

Erick Erickson

Erick Erickson is a writer, a columnist, and the host of "The Erick Erickson Show" on 95.5 WSB. Erickson received his law degree from Mercer University's Walter F. George School of Law and practiced for six years, primarily at Sell & Melton LLP. Erickson subsequently served as editor in chief at RedState.com for a decade, as a political contributor at both CNN and Fox News for several years, and as a city councilman for Macon, Georgia.

Erickson, a proud member of the Presbyterian Church in America who has started on a theology degree at Reformed Theological Seminary, has a book out later this month entitled, "You Shall Be as Gods: Pagans, Progressives, and the Rise of the Woke Gnostic Left," which explores the longstanding conflict between the Christian church today and paganism.

In his phone interview with Blaze News, Erickson minced no words about the reality of hell and the torments that await those who have rejected Christ. However, he emphasized that it is not by the cruelty of God that some men are damned but by His love and mercy that they could ever be saved.

Real and everlasting

Erickson indicated at the outset that the Presbyterian Church of America follows the Westminster Confession of Faith, which was produced by the Westminster Assembly during the English Civil War and completed in 1646.

The Westminster Confession affirms that the Bible in its original languages is pure and remains the infallible source of doctrinal authority for Christian faith. The document is also unmistakably clear about Presbyterian beliefs in the afterlife — as was Erickson.

'Those who are separated from God will be there eternally.'

"Yes, hell is real, and it is eternal," said Erickson. "It is a physical place" where the devil, the demons, and the damned all ultimately go.

The conservative host noted that after the day of judgment, "Those who are separated from God will be there eternally" immediately upon dying. There is no transitional period or purgatorial state getting in the way of damned souls' encounter with final consequence.

In terms of its relation in time and space to heaven, Erickson noted that "whether we view it as inside or outside the gates of heaven, there is some physical location outside the realm of God where those who are not of the kingdom of God will go."

Apathy be damned

The Westminster Confession states, "By the decree of God, for the manifestation of his glory, some men and angels are predestinated unto everlasting life, and others fore-ordained to everlasting death."

When asked about this belief that God predestines some souls to hell, Erickson indicated that Presbyterians and Calvinists believe "there are those God elected to save and all others not to save."

'God clearly wants a relationship with us.'

Erickson indicated that "if you desire to be with God, then you're among the elect. If you have no interest or desire, then you're not."

"God clearly wants a relationship with us. He sent Jesus to live a perfect life in this world, to try to call everyone to Him," said Erickson. "I definitely think there is a portion of the people who reject God who, through their own stubbornness, wind up there."

While some Christians might find the idea of predestination difficult to digest, Erickson alternatively indicated, "I have a hard time understanding why we get to heaven. I mean, I'm amazed by God's love to allow us, knowing all of the sins of my life."

Once saved, always saved

To avoid hell, actions aren't going to cut it. After all, no one is good enough on their own merit — either for heaven or to pay back the sacrifice at Golgotha. The key, stressed Erickson, is faith in Jesus Christ. Such is the way of salvation.

Blaze News asked Erickson whether people who genuinely have faith in Christ could jeopardize their salvation and guarantee a fast-track to hell through some misstep in word or deed.

'If you put your faith in Christ and trust Him, you can't be snatched away from Him.'

"So, the 'once saved, always saved,' is something a lot of evangelicals would say; that if you are saved, you can't be snatched away from Christ," said Erickson. "Whether or not you are saved — you may think you are and you're not — that's between you and God, not for me to decide. But the general rule is, if you put your faith in Christ and trust Him, you can't be snatched away from Him."

Whereas other denominations might be less committal in their responses, Erickson indicated that those who do not accept Christ, including nonbelievers, are precluded from going to heaven and thereby consigned to hell. This is cause, he acknowledged, for Christians to proselytize.

"I think a lot of denominations that believe in predestination and the doctrine of election are asked, 'Well, why bother doing these things if God's got it and the Holy Spirit's in charge?'" said Erickson. "We are instruments of God's will, and we are called to evangelize, and Christ tells us in the Great Commission to preach, teach, and baptize in His name."

Erickson suggested that hell is likely not egalitarian in the way of the punishments. Accordingly, those unfortunate enough to wind up there having never before heard of Christ won't suffer to the extent of a truly wicked person for all time.

"I don't know that I would say it's PCA because we don't get into it a lot," said Erickson, "[but] I do think that there are levels of separation from God. Those who do terrible things are punished more than those who just never knew Christ."

Just as Dante figured the great minds of antiquity would be stuck in the first circle of Dante's hell, Erickson suggested that there may be gradations of suffering and that such people may just experience "an absence of God as opposed to active punishment."

Downplaying the depths

Blaze News asked Erickson about the efforts by some denominations to downplay the existence of hell. The conservative host indicated that in doing so, they effectively water down Christ's own teachings.

'Christ Himself didn't speak in red letters.'

"I think Jesus Himself spoke more about hell than anyone else in Scripture and for any denomination to downplay hell is downplaying a significant portion of the things Christ talked about," said Erickson.

"I mean, there is an aspect of some Christian denominations that take a red-letter view — that they only pay attention to the red letters in the New Testament, which some editor centuries ago put in," continued Erickson. "Christ Himself didn't speak in red letters, but within those red letters are a lot of discussions of hell, damnation, and judgment. So, to be dismissive of that is to be dismissive of a whole lot of what Christ talked about."

Erickson acknowledged a possible correlation between the narrative elimination of the possibility of hell and the laxation of morals, noting that "'secular, secularism,' translated actually means 'nowism'; that only the here and now matters. And there is a lot of that, I think, that even creeps into the church to be so focused on the here and now that we forget about eternity."

Besides possibly impacting public morality, the effort to discount the existence of hell also has theological implications.

"You know Tim Keller, one of the more famous PCA pastors, before he passed away said, 'Unless you accept that the devil and hell were real, a lot of Scripture doesn't make sense.'"

The story of salvation, too, would be undercut by the notion there is no hell.

"Why do we need to be saved if there is no eternal punishment?" said Erickson.

Additionally, there is a comfort in recognizing hell's existence. After all, oftentimes evildoers escape justice in the temporal realm.

"The doctrine of hell gives me comfort that there are those who are terrible people who will get away with terrible things in this lifetime, but they'll never escape judgment," Erickson told Blaze News. "I wouldn't want to believe in a God that could look on the horrors of this world and say, 'Well, that guy gets in too.'"

While Erickson expressed uncertainty about whether a broader belief in hell might yield social benefits today, he said it certainly helps people of faith, affording them "some level of calibration to, I think, be empathetic to those who are not saved; to understand that this is the best they're going to have; and to be relational and perhaps save those who otherwise would not be with you in heaven."

Rabbi Shana Goldstein Mackler

Rabbi Shana Goldstein Mackler has been serving for 20 years as a rabbi at the Temple, Congregation Ohabai Sholom in Nashville, where she is now also a senior scholar.

Rabbi Mackler, a teacher at the Hebrew Day School of Central Florida, was voted one of America's Most Inspiring Rabbis in 2016 and is both a founding member of the West Nashville Interfaith Clergy Group and president of the Nashville Board of Rabbis. She and her husband, Army veteran Lt. Col. James Mackler, are the proud parents of two daughters.

At the outset, Rabbi Mackler clarified to Blaze News over the phone that a distinguishing feature of Reform Judaism, of which she is an exponent, when it comes to ritual laws, "Reformed Judaism feels guided by the ritual commandments and the more orthodox feels governed by them."

Heaven on earth and hell in question

Rabbi Mackler emphasized that Jewish views on the afterlife and the possibility of hell differ wildly: "For as many Jews as there are in the world, there's probably that many opinions on the afterlife."

"The texts in virtually every era of Jewish life have some sort of concept of a world where people go when they die. In the Bible, there is this concept of Sheol. It's not very specific," said Rabbi Mackler. "It takes on different names through our rabbinic tradition (e.g., 'Shamayim'), which comes about after the Hebrew Bible was closed."

'We don't focus as much on the next life as we do on this life.'

A lack of textual specificity and the emergence of various interpretations have apparently all but guaranteed the impossibility of consensus, but there appears to be little urgency given the Jewish focus on the here and now as opposed to the hereafter, suggested Rabbi Mackler.

"We don't focus as much on the next life as we do on this life so the concept of that as a reward or punishment is not really the focus of Jewish practice," said the rabbi. "Most of us focus on trying to make whatever our concept of paradise is here on earth."

As for hell, individuals may try to generate pockets of it on earth, but Rabbi Mackler indicated there's no such place awaiting us after death.

'We don't have fire and brimstone.'

"We do not have a concept of hell," said Rabbi Mackler. "We don't have the devil. We don't have fire and brimstone. We don't have any of that. That's not our concept at all. So, I think that's a big difference for us: We just don't have that form of punishment."

There is, however, a minority of Reform Jews — perhaps even among her congregation — who believe otherwise.

An appetite whetted for justice

Rabbi Mackler indicated that over time and through acculturation, particularly when living in diaspora, some Jews have adopted views on the afterlife that may be more recognizable to mainstream Christians.

"Everywhere we went, we were influenced by the people among whom we lived. And so some of the concepts like the Hellenistic concept of Hades — those kind of things you can see finding their way into some literature at some point in time," Rabbi Mackler told Blaze News. "I would say that because hell is very much a [popular] concept in our modern life ... it makes its way into someone's psyche, regardless of their religious focus."

Rabbi Mackler noted that these views also resonated with concepts already in Judaism, particularly in Deuteronomy, which advances the understanding that the righteous will be rewarded and the wicked will be punished. Bereft of a sense of justice in this world, the rabbi noted that the desire for an afterlife became all the more appealing.

"We see lots of things where the wicked people get success or they get elevated or they get famous or whatever the benefit is that they're seeking, and righteous people suffer. So, I think there was a question, and Job actually ultimately asked the question, 'Why do righteous people suffer?'" said Rabbi Mackler. "I think the idea of the world to come was an avenue for that to be worked out."

"So, if it didn't happen in our lifetime for the righteous to be rewarded and the wicked to be punished, I think that was really where it was a need for people to see that for following the rules and keeping all of the commandments that we're supposed to do, it will eventually happen, even though we may not see it in our own lifetime," added the rabbi.

The influence of other cultures' views on hell, the biblically grounded promise of justice, and the human desire to see the haughty fall have apparently prompted some Jews to believe in the existence of hell.

Posthumous waiting room

Rabbi Mackler told Blaze News that while souls may not ultimately face the possibility of hell, some Jews believe in a "sort of waiting period" that souls must endure after death — a "transitional period between the death and maybe the ultimate."

"You know, there is a view of resurrection — not everybody believes in that, but it's collective, it's not an individual resurrection; it's going to be a collective, communal thing at the end of days," said the rabbi. "If that is part of their belief system, there is sort of a waiting period to get there."

The belief in the existence in such a waiting period corresponds with the practice of praying over the course of the year following the death of a loved one, "which is thought to be one of those ways that we can elevate that soul."

Memory and special cases

Truly reprehensible individuals could be altogether precluded from joining the posthumous waiting room, speculated the rabbi. At the very least, their immorality could mean their temporal erasure.

Concerning the person who renounces God or faith or morality in this world, Rabbi Mackler said, "There is a thought that they would be cut off from their kin. The idea of not being part of a community, of alienating yourself like that; like that's the punishment itself. The worst thing that we could have is not leaving a mark in this world, right."

In Reform Judaism — and perhaps Judaism more broadly — memory, morality, and the afterlife appear to be strongly linked.

Alienation from the community could mean annihilation in, at the very least, the worldly sense. After all, the memories of the faithful departed are alternatively kept alive in regular prayers.

"I don't know if you know but there is a concept called the 'minyan,' like not the little yellow guys," said Rabbi Mackler. "It's a quorum, a number of people that's needed for a prayer. So, when Jews get together to pray, we need that quorum for certain prayers to be said. They can pray alone, but the ideal is to pray in community or to read the Torah, the sacred Scriptures, in community or to grieve in community."

"So, that's how memory gets passed on, whether it's out of collective peoples' memory or our individual memories of people," continued the rabbi. "We to this day will read the names of people that none of us knows, but every Friday night when we have our Sabbath prayer, we have what's called Kaddish."

"So, we will recite their names on the anniversary of their passing, and when someone dies, we also have not just on their anniversary, but four times throughout the year on certain holidays, we have a memorial service. So, people are constantly being remembered," added Rabbi Mackler.

Extra to working against the establishment of a better world, the truly wicked person all but guarantees he will not be remembered in this manner.

'It's like nothingness, right.'

"So, the idea that we wouldn't be positively furthering the world — that, in and of itself, not being remembered for our blessing — would be the punishment that we would get," added the rabbi.

'They'll cease to be, perhaps.'

Blaze News pressed the issue of what would happen to a truly evil soul. Rabbi Mackler replied, "A lot of people really think about that, but because they don't really have a formed concept of hell, all we could say is that they will not have a share in the world to come. It's like nothingness, right. They'll cease to be, perhaps. I mean, this is conjecture."

"The only time that we really know about an afterlife is that people are remembered," added Mackler. "And we say, 'remembered for our blessing,' and so that's the legacy we leave and is how people will remember you. For us, that's the worst of the worst, right."

Regarding incentives for good behavior

Rabbi Mackler noted there is a concept of acting out of fear of retribution and punishment "in the Bible, the Torah itself, where there are blessings and curses; if you do these things, if you don't do these things."

While Judaism contains within it a sense that good deeds will be rewarded and bad deeds will be punished, the trouble, according to Rabbi Mackler, is that behavior shaped by external threats of final rewards and punishments is "not the way that a free person behaves."

"That's not the ideal of a free person, a person that's created in the image of God, a person that has agency in this world," said the rabbi. "We're supposed to choose it for ourselves to do right, to do good, instead out of fear of something else coming at the end of our life."

Rabbi Mackler did highlight, however, that moral choices nevertheless have real consequences.

"The punishment itself I think comes from when we don't have a world we want to live in if we create the curses ourselves by the choices that we make collectively," said the rabbi. "So, I think there's that collective responsibility piece that might be more challenging for me to have this idea of each person having a tally, you know: things that will get them into heaven or things that will send them to hell."

In Part I, Archbishop Emeritus Cardinal Thomas Collins details the Roman Catholic views on hell and mortal sin, and Rabbi Aron Moss discusses the "kindness" of hell and the nature of Gehinnom.

In Part II, Rev. Fr. Calvin Robinson discusses the reality of hell from a British Old Catholic perspective; Rev. Dr. Lance Haverkamp discusses the Christian Universalist belief that all souls will ultimately be saved, possibly negating the need for hell; Bishop Stephen Andrews provides an Anglican perspective on the darker side of the afterlife; and Dr. Kenneth Green provides historical insights into Jewish views on Gehenna.

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!