![]()

Lee Edwards passed away peacefully Thursday morning. He was an incredible man and a witness to history, known to many as the historian of American conservativism. But more than that, he was a gentle and caring soul who nurtured and mentored the future even as he studiously preserved the past.

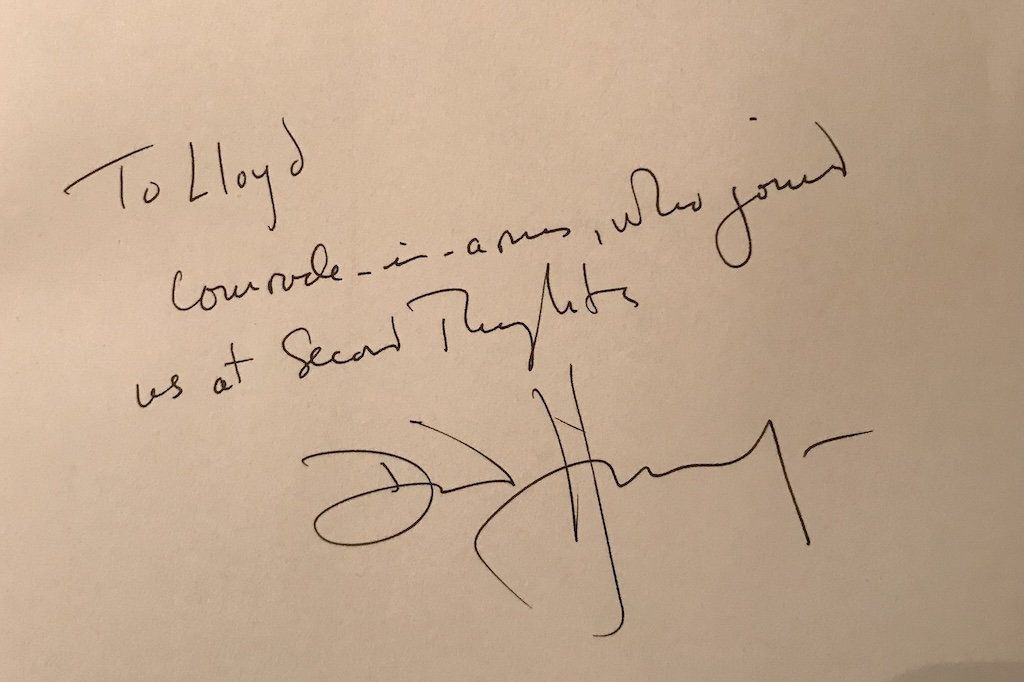

I first met Lee 14 years ago at Cafe Berlin, a favorite of his that reminded him of his time in Germany with the U.S. Army. Alongside some pals, I’d just relaunched Young Americans for Freedom’s New Guard magazine — long a voice for the new right, but by then defunct nearly 20 years. Lee had founded the magazine in 1961 and edited it for years before handing it on. We brought a 50-year-old copy of his first issue and a fresh print of our own.

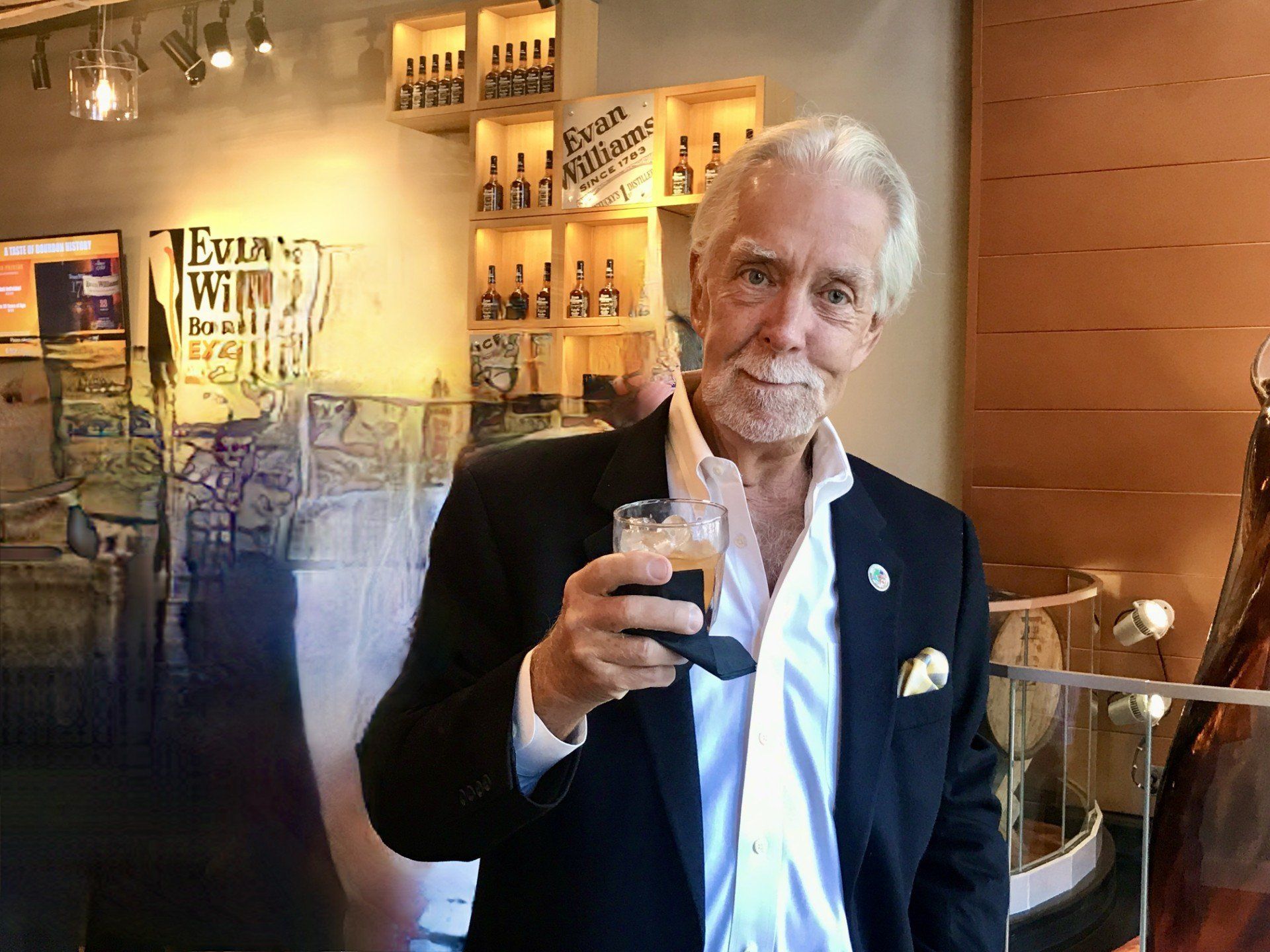

He was flattered but cautious. Prudence was a quality he both valued and practiced. But I guess he liked what he read. The next time we met, he gave me a first edition of National Review No. 1 alongside words of advice and encouragement. Over the next decade and a half, we’d meet for lunch or at his classroom at Catholic University or when he came to lecture up-and-coming reporters for me. He always asked about what I was working on, and more than once, his gentle, unspoken look of skepticism put me back on track (though there’s something to say for that year reviewing beer and liquor in exchange for free samples).

Eight years ago, I wrote a profile of him for the Daily Caller that followed his life from occupied Germany to the left bank of the Seine and from Barry Goldwater and Bill Buckley to Ronald Reagan and anti-communism. You can read it in full below.

Lee was a kind man. He was a writer and a teacher who loved his children, his grandchildren, the church, and the Lord. He loved his wife and missed her terribly after she passed just over two years ago. When I last visited him this summer after the cancer diagnosis he bore so bravely, a beautiful photograph from their wedding day hung in the entryway among the photos of generations that grew up around their love. We’ll miss him here, but it’s wonderful to know he’s home, reunited both with God and with Anne.

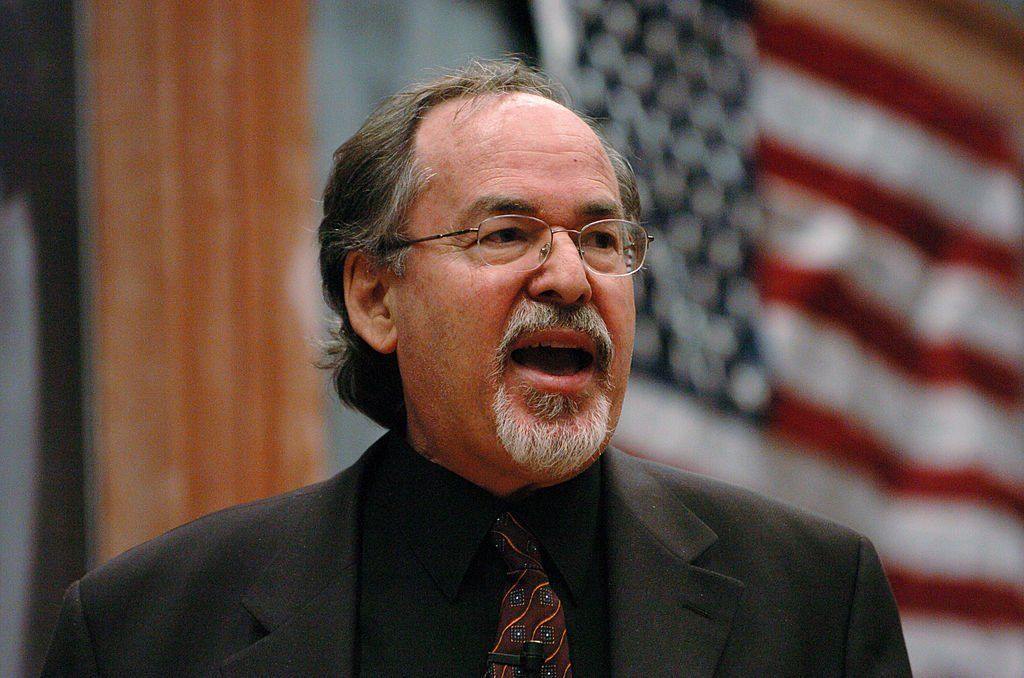

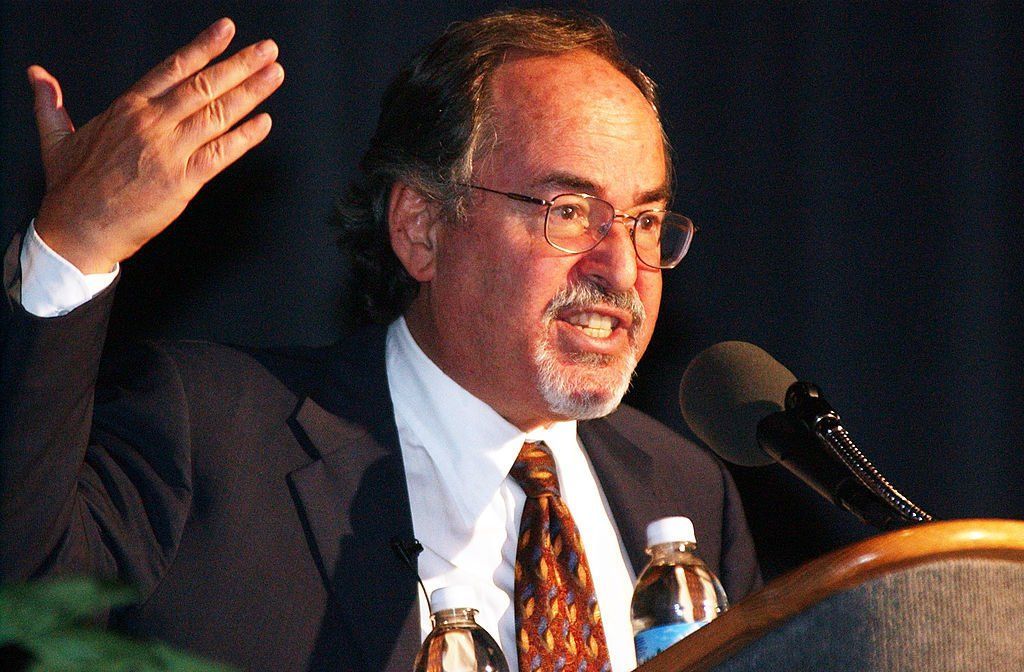

This man, ‘the Voice of the Silent Majority’ for a half-century, has lived conservative history like none other

The New York Times called Lee Edwards "the voice of 'the Silent Majority,'" as he stood among 25,000 Americans he had gathered at the Washington Monument to support U.S. soldiers in Vietnam. It was November 1969.

At 36, he had spent the past decade at the birth of American political conservatism. He’d helped found Young Americans for Freedom in 1960 at William F. Buckley’s estate and launched their magazine, the New Guard, in ’61; he’d worked to pack Madison Square Garden with 20,000 anti-Communists in 1962; served as the press director for Sen. Barry Goldwater’s seminal presidential campaign in ’64; traveled with Ronald Reagan as he geared up to run for California governor in ’65; and covered Richard Nixon in 1968. At 36, he was at the top of his game. And he was about to leave that life behind.

On a cloudy Tuesday morning in August, two weeks after the Republican Party nominated Donald Trump for president of the United States, Lee is standing in the handsome, dark-wood-trimmed seventh-floor theater of Washington, D.C.’s Heritage Foundation, looking out the window at the city he’s made home for most of his 83 years.

In this room, Lee has sat alongside thinkers from Friedrich Hayek to George Will. And to a casual tourist, it offers stunning views of Union Station and the U.S. Capitol. But from here, Lee can also see the Dirksen Senate building, where he was press secretary to Sen. John Marshall Butler — “what a name!” — from ’59 to ’62. And most essentially — the reason, I suspect, he brought me up here — he can glimpse his proudest accomplishment of the life he left PR for.

'Lots of 20-somethings in DC pontificate. What about experience, wisdom? Lee is not just an historian of the conservative movement, he’s someone who shaped it.'

Ninety-nine years after Russia’s October Revolution, the Victims of Communism Memorial stands at the corner of Massachusetts and New Jersey Avenues, in silent watch for the millions who died, and the millions more who still toil, under communism.

“I was really an anti-communist before economics,” Lee muses, “but I’ll tell you more about that later.”

In the past two weeks, Lee had been busy. He was at FreedomFest, where he’d lectured, presented, and debated at the slightly wild Las Vegas conference hosted by Mark Skousen, a libertarian economist and descendant of Ben Franklin. He’d also met former Islamist Tawfik Hamid and introduced Angela Keaton, executive director of the radical Antiwar.com. “She’s very intelligent,” he beams. Then he’d caught a 6 a.m. flight to his 13th Republican National Convention, where he marveled at how the reporters’ media center teemed not just with young men, but young women as well.

And everyone was here covering the nominee: one Donald J. Trump.

“It’s a different party,” the veteran conservative concedes. “Used to be Big Tent, with moderates, liberals like [Gov. Nelson] Rockefeller. [Rep. Walter] Judd was a strong anti-communist for limited government, but a liberal on welfare and immigration.”

Starting in 1972, Sen. George McGovern began the Democratic Party’s long march to a progressive party where an open socialist can nearly win the nomination. The Republican Party’s march began just a few years earlier in 1964. It is still Lee’s favorite convention.

On Friday, Nov. 22, 1963, an excited Lee was having lunch with an old friend at the Capitol Hilton. Lee had been hired on full-time as the news director for the Goldwater for President campaign he and thousands of others had worked for years to make a reality. That Monday, he was due to report at the campaign offices. But that afternoon, the hotel TVs changed his schedule: The president had been shot in Dallas, a town that, later that day, the Voice of America radio station would indict as the heart of “Goldwaterland” — a myth that still persists today.

No one was at the office when Lee bolted in. The campaign heads were on the road in a day before cell phones, and Sen. Goldwater and his wife were on their way to her mother’s funeral in Indiana. It was Lee on his own, three days before his start date, and the phones were blaring.

“There were two types of calls,” Lee remembers. The first were reporters looking for a statement. “I’ll get back to you” was all he could promise. The second type of calls left no room for reply.

“Murderers!” Click.

“Right-wing crazies!” Click.

“There’s a bomb in your office.” Click.

Lee had first seen Goldwater in action when working as a Senate aide. By then, the Arizona senator was already a conservative hero. “The Conscience of a Conservative” had come out in 1960 and had lit a fire with activists like those in Young Americans for Freedom, who, alongside co-founder Lee Edwards, filled the Manhattan Center for the Arizona senator in ’61 and then Madison Square Garden in ’62, where thousands of eager fans in New York City — the capital of American liberalism — had to be turned away because there was no more room. Lee volunteered on the Draft Goldwater Committee, which devoted its efforts to convincing the Arizonan he could beat his friend John F. Kennedy.

In October 1963 — the month before Dallas — Time magazine had called a matchup between the two men “a breathlessly close race,” but those November gunshots changed everything. It would no longer be a competition of ideas between two men who respected and liked each other, but a cut-throat battle with a Texan Goldwater had scarcely concealed contempt for. And, Goldwater later posited, “the American people were not ready for three presidents in little more than one year.”

As that long Friday wore on, Lee was finally able to get ahold of the campaign leaders, draft a response, and close the office down for a period of national mourning. His job might be over before it had begun: The rumor that Goldwater won’t run now that Kennedy had been killed spread quickly through the capital city.

But the senator’s most idealistic supporters were undeterred. “We young conservatives unleashed a tidal wave of letters, calls, telegrams — and some demonstrations — for Goldwater to run,” Lee recalls. Young activists’ yearning for a hero, Goldwater would later admit, was critical to his decision to run a doomed campaign.

The next fall, following a series of stumbles on nuclear weapons and Social Security, Goldwater was crushed in New Hampshire’s Republican primary. “Lee,” he privately said, “you don’t know how much trouble I am going to cause you.”

“Hint: I did.”

Some children rebel against their parents. Lee, born to an anti-communist newspaper man and an English teacher on the South Side of Chicago in 1932, did not. At least not in the long run.

“I was always a writer. I define myself that way,” he tells me. “It’s what I do.”

But that didn’t quite mean following in his father’s formidable footsteps right away. “I graduated college and volunteered” for the U.S. Army, heading to Heidelberg, Germany, to work for the Signal Corps, transmitting communications across the continent as the Iron Curtain descended.

It wasn’t exciting work. “Get up, put on your uniform, go to work, then drink as many beers as you could down at the E.M. [Enlisted Men] Club,” he says. But it was a chance to branch out from his upbringing. “I could have been an officer, but I wanted to be a writer, among the men,” Lee says, adding later, “The first blacks I ever met in my life were in my company, other than a maid. Washington was a segregated city.”

And he got a taste for a different life while at it, after the Army moving to Paris’ Left Bank (“because it was cheap”), studying at the Sorbonne, and writing poetry and short stories. “I wanted to be the next Ernest Hemingway,” he laughs. “Talk about an exaggerated sense of yourself!”

It was in Paris that he wrote his first novel. And it was also in Paris where he heard the young people of Hungary joyously yell, “We’re free!” on the radio. That was 1956 — before the Soviet tanks rolled in, slaughtering the dissidents while the West stayed silent. The silence stuck with him his entire life. The book didn’t sell. He was running out of money, the hangovers were getting worse, and the rejection slips were piling up.

“It really was a dream,” he reflects. “I just wasn’t that good; I didn’t have the imaginative gift.” France was “my one rebellion against my parents. Part of it was my dad was so well known I didn’t want to compete in journalism.”

Lee’s father, Willard Edwards, was a tough, hard-drinking, old-fashioned reporter. He began his half-century career at the Chicago Tribune in the 1920s, with his first assignment covering a gangland barbershop where two men had been shot in the head while getting a shave. A year after his only son was born, the family moved to Washington, D.C., where he would cover politics for the thoroughly anti-New Deal newspaper.

In D.C., Willard took to the Soviet influence beat with enthusiasm, breaking so many stories the communist New York Daily Worker dubbed him “one of the most dangerous” reporters in the country. His work caught the eye of powerful politicians, including then-Rep. Richard Nixon, who decades later wrote to Willard’s son Lee, “Speaking of heroes, your father rates in that respect with me.”

In 1950, when a GOP senator was preparing a speech to commemorate Abraham Lincoln’s birthday at a Republican club in West Virginia, his staff, looking for an exciting topic, went to the Senate reporter gallery to “dig something up,” writes Donald Ritchie in his book, “Reporting from Washington.”

“Going to the Senate press gallery, [Senate aide George] Waters sought out a Chicago Tribune correspondent, Willard Edwards, whose series on communism in government had been running in the Tribune and its sister paper, the Washington Times-Herald. Edwards obliged, turning over his files,” which the senator’s staff added to their material to craft “a series of talking points.” The senator was Joseph McCarthy, a man Willard would later describe as “irresponsible,” but whom the reporter would become such an authority on, he “was a research source during his retirement for authors writing about McCarthy,” the Tribune reported in his 1990 obituary.

But when Lee returned from Europe in 1956, he wasn’t too interested in politics, writing fiction for Human Events and William F. Buckley’s National Review. When fellow writer M. Stanton “Stan” Evans cajoled Lee into attending a D.C. Young Republicans meeting and supporting him for club president, it led to editing their newspaper, an invitation to Buckley’s family estate, the creation of Young Americans for Freedom, the founding of the New Guard magazine, and 20 years of political activism.

“Stan said there’d be pretty girls there,” Lee laughs.

As the 1964 campaign gained speed, Lee was excited to be a part of it, working as the traveling secretary and scrambling to put out brush fires while his fiercely independent candidate took shot after shot from political and media opponents across the country. Then, in poor health, the communications director stepped aside. His replacement, who struggled with the drink, was in no shape himself. And suddenly, there was Lee.

“Because of somebody’s bad heart and [another’s] alcoholism, I got to be the director,” Lee marvels. “I was, what, 31? And inexperienced, to say the least — I’d ran a few congressional campaigns. But I did all right. You learn a lot quickly.”

There was a picture hanging in the office, back then, of Lee. The staff labeled it “Benevolent Dictator.”

“I think I’ve become more benevolent over the years,” he chuckles.

The Victim of Communism Memorial Foundation keeps its offices in a modern, steel-and-glass office building near Capitol Hill, one mile east of the Spy Museum, five blocks north of the U.S. Capitol, and two blocks south of a 10-foot bronze replica of the Goddess of Democracy, sculpted after the paper mache statue carried by the protesters at Tiananmen Square.

Signed into law by President Bill Clinton in 1993, the memorial was dedicated by George W. Bush in 2007, the 20th anniversary of Ronald Reagan’s Brandenburg Gate challenge to the Soviet Union.

When we walked into the office, a half-dozen young people jumped to attention, eager to shake hands with the foundation’s chairman. Past a lobby adorned with pictures of Siberia painted by a former prisoner of Josef Stalin, we entered the office of Marion Smith, the executive director of Victims of Communism, who left Heritage to join the effort.

A WWII poster hangs on the wall, depicting U.S. soldiers marching past the ghosts of Valley Forge. “America will always fight for liberty,” it reads. Beside it, a sign warning past visitors they are “exiting the American zone” at Berlin’s Checkpoint Charlie, a place a younger Lee once visited. A bust of Karl Marx sits nearby, on a desk by the door. A structural pillar proudly reads, “Dissident.”

Back when Marion left Heritage after two and a half years working for Lee’s son-in-law, it was hard to make the case for the change in jobs, he tells me. No longer. Everyone we meet now gives “us new info in what we do being relevant,” he says. “We’ve lost Hong Kong, lost parts of Georgia, lost the Crimea and parts of Ukraine. The free world is shrinking. China is in South America and in African colonies while the West is crumbling.”

“We were founded because people were forgetting what communism is, why we fought the Cold War, and the 100 million victims,” Lee says. “Nazis may be the most evil of the 20th century, but communists were the most deadly.”

“My office and brain are at Heritage,” Lee adds. “My heart is here.”

And their plans are ambitious: a memorial museum, inspired by D.C.’s Holocaust Museum, with an announcement coming by October or November next year — in time for the 100-year anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution.

As a lack of foreign policy agreement grips the country, an avowed socialist leads an army of young Americans, and Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping march on the globe, the need for a museum is crucial, the two argue. The White House touts the opening of Cuba, Marion points out, where there have been 8,000 arbitrary arrests since May, beating last year’s total, “which was already bad.” Polls show ignorance on basic economics and 20th-century history, coupled with a strong belief in government — “the cult of the state.”

“Things,” he tells me, “have objectively gotten worse.” In the beginning, Lee says, VoC focused on the past and would have been happy to stick to it, but “mission has been thrust upon us by reason of what’s going on in the [world].”

“It cannot go unchallenged, unanalyzed. More people live under communism now than in 1989. It’s far from the ash heap of history.”

And their efforts have not gone unnoticed by the totalitarians they target. Communists came in third in a recent Czech election, promptly taking control of VoC’s sister group and shutting down access to the archives of past crimes. Russian websites mixing VoC writings and Nazi propaganda have popped up online in an effort to discredit them. The online harassment is constant.

Just this past April, as VoC geared up for its annual commemoration of the Tiananmen Square massacre, I received a 7 a.m. text from Marion asking if one of our reporters could get downtown ASAP: They were under what they would find to be a “major, multi-pronged, coordinated, week-long cyber attack.”

China was “so threatened by contested history, they devoted a cyber unit’s week to disruption,” Marion tells me, shutting down the site and disrupting operations. These days, they’re even targeted by op-eds in the Chinese government’s newspaper, People’s Daily. “So we’re climbing up,” he laughs.

The movement could make a difference closer to home, Lee observes. “The anti-totalitarian impulse — versus Putin, Xi, Castro, Islamism — could once again be the glue for the right.”

Back at his book-stacked office, a life on the right is laid out in academic splendor. His desk is covered with books about Russell Kirk, whom he is busy writing an article on. Reagan books are on the right; poetry, politics, and foreign affairs adorn a middle shelf; books on communism fill the left. Behind his chair, his own books intermingle with writings on philosophy. A replica of the memorial he built anchors a corner. A small wooden crucifix hangs on the wall, and the 2016 RNC platform sits neatly stacked on the floor, beside newspaper clippings, both old and new.

Since leaving public relations, Lee has relished academia, founding Georgetown’s Institute of Political Journalism, serving as a fellow at Harvard University and the Hoover Institution, presiding over the Philadelphia Society, and now 30 years teaching at Catholic University, a faith he converted to in 1958, shortly after his return from Europe.

Beside the door, an old photo shows his father as he covered Eleanor Roosevelt at the 1940 Democratic National Convention. She was the first woman to address a national convention. There’s the Taiwan Friendship Medal of Diplomacy; a signed ’64 portrait to “a stalwart friend” from Goldwater; degrees from Catholic University, Harvard, and Grove City; pictures with Presidents Richard Nixon, George H.W. Bush, George W., and one Ronald Reagan.

“I pitched Reader's Digest on a Reagan profile in 1965,” Lee tells me. “He’d been on the road testing the waters [to run for governor] and studying problems in California. We spent two days with him: picked him up in the morning, drove around to five or six speeches over two days. The driver and Anne sat in the front, and there was me and my Wollensak [interview recorder] in the back with Reagan. Wollensaks were as big as a suitcase back then. The recordings still exist.”

In 1965, Reagan was a fairly well-known movie actor and a spokesman for General Electric. His televised speech for Goldwater, “A Time for Choosing,” had catapulted him to conservative stardom. Still, few were sure how serious a man he was, including Lee. At first.

At the end of the second day, Reagan invited Lee and Anne up to his house for iced tea and cookies. They called it “the GE Home,” nicknamed for all the futuristic gadgets the company had given him over the years. Sitting in the study, Lee’s eyes were drawn to the bookshelves, where, besides classics and books on the West and California, there were deep-thinking tomes: Whittaker Chambers’ “Witness,” Henry Hazlitt’s “Economics in One Lesson,” Friedrich Hayek’s “Road to Serfdom,” and then one Lee had never heard of — “The Law,” by Frederic Bastiat. Doubtful, curious, and over his wife’s objections, “I opened them to see if he’d read them,” Lee confesses in his office. “They were all dog-eared, with notes in the margins. He’d studied them.”

In 1967, Lee wrote the first biography of the future president, succinctly titled, “Ronald Reagan: A Political Biography.” It was the best-selling of the 25 books he’s written, moving 175,000 copies and prompting a reissue in 1981, to which the publisher gauchely added, “Complete Through the Assassination Attempt.” In the Oval Office, leafing through the newest copy, Reagan apologized to Lee, rasping, “Well, I’m sorry I messed up your ending.”

A short speech from Reagan roasting Lee for his public-relations retirement party hangs on the wall at his office at the Heritage Foundation, where he’s worked full-time the past 15 years, writing books and acting as American conservatism’s unofficial historian and keeper of records, dutifully documenting the crimes and triumphs of friends and foes. He wrote his most recent book, “A Brief History of the Cold War," with his daughter Elizabeth Edwards Spalding, for students and teachers to get the story right.

“Lots of 20-somethings in D.C. pontificate,” Heritage’s David Azerrad tells me after lunch at the nearby Cafe Berlin, a simple restaurant that reminds Lee of his years in Germany. “What about experience, wisdom? Lee is not just an historian of the conservative movement, he’s someone who shaped it. Goldwater, National Review, Young Americans for Freedom, Bill Buckley, Russell Kirk, Human Events.”

“Alongside feminism, environmentalism, and multiculturalism, [historian] George Nash puts conservatism in the major changes in society in the past 40 years,” Azerrad continues. “Lee brings that history." And today, he adds, “Old conservatives, especially, are dispirited. They’re serious, dour. And there is much to find dispiriting. But Lee keeps a smile, and it’s a testimony to his good nature: He’s a political animal smart enough to realize there’s life outside politics.”

“What do you think about the Republican Party today — how it’s changed?” I ask Lee.

“Is it better to have a big tent?” he answers slowly and deliberately. “Or two parties, clearly separate? ‘A choice, not an echo,'” he offers, quoting Goldwater’s presidential announcement.

“I believe there is a silent majority out there,” says the man once called its voice. “Nixon gave voice to it, and I believe Reagan gave voice to it.”

“I have no intention of retiring,” he smiles.

Photo by Lloyd Billingsley

Photo by Lloyd Billingsley