![]()

This article originally appeared in the first print issue of Return.

An element of legends is that they never really happened. They are believed but not true. The urban legend emphasizes that city dwellers and moderns can be total hicks in epistemic terms, just as much as rural people and people of the past. But when used on Twitter, the term “urban legend” usually just means that a story is false. The essence of an urban legend is a story that is untrue, yet believed.

An interesting comment on the debate of linguistic prescriptivism versus descriptivism is that people are naturally prescriptivist. When encountering poor usage or diction, humans seem to experience a range of emotions, from a vague sense of wrongness or mild irritation all the way to rage in some cases. So if descriptivism is correct, what are these emotions for?

As an outsider to human culture, I see people wanting to keep their language commons clean and tidy for better usability. People clear up clothing and other artifacts that may block interior pathways and clear up snow and debris outdoors so that their environment is usable; possibly a similar range of emotions motivates them to do so (from a sense of wrongness to anger), as well as a desire to prevent these emotions from occurring in others.

I think something similar is going on with Wrong on the Internet, a phenomenon not limited to the internet, in which wrong information induces a range of epistemic emotions from an uncomfortable feeling to mild irritation all the way to epistemic rage. People want to keep the knowledge commons clean and usable, and a balance must be struck between the entertainment value of information and its underlying validity. Toys are amusing but must not be left in hallways for people to trip over; similarly, amazing stories are fun and valuable but must not be left in places where they are easily mistaken for truth.

'Told for true'

In folklore studies, “told for true” is the term of art to distinguish legends that are meant to be believed by their audience and hence open to doubt from fairy tales (Märchen), which, through their formal elements and fantastical content, signal to the reader that they are neither to be believed nor doubted. Few hear words like “Once upon a time, there was a mouse king” and think, “Whoa, did that really happen?” In practice, however, the distinction is not so tidy. A web comic may feature fantastical elements such as unicorns and talking frogs, but if the animals comment on current events, it might properly be judged to contain truth claims. And many stories about fantastical beings and happenings are told for true to this day.

But there is another element to legends, including urban legends: They are stories that never really happened. They are believed but not true. Folklorists rarely concern themselves with the truth of stories; they focus on collecting tales, tracing them to their origins when possible, and connecting their themes with those of older story traditions, rather than debunking (or supporting) them. A believed story that is true doesn’t arouse epistemic emotions, nor does a false story understood to be fiction or a joke.

The power of the memorat

Within the field of folklore, another common characteristic of the urban legend is that it is told as the experience of a “friend of a friend,” where a vague social connection is implied, but it is not told as the experience of the teller. If it were the teller’s own experience, that would make it a memorat in folklore jargon. However, most legends usually originate in a memorat form, and legends may be retold as memorat by speakers wishing to spice up interviews or talks. In practice, people seem to switch between forms effortlessly when telling stories, now telling what they heard as a child, now telling their own experiences.

The term “urban legend” puts the fault for the falsehood on the story itself, rather than on the teller, who is merely a dupe. But accusing someone of telling a story of their own experience that isn’t true is essentially accusing the teller of lying. That is unfortunate, as memorats constitute the bulk of interesting folklore in our time. Personal experiences posted to told-for-true Reddit boards (such as r/homeowners or r/legaladvice), performed in told-for-true formats like TED Talks or podcasts, or written up as case reports or syndrome letters, are taken for true and rarely doubted, as doubting would constitute an antisocial accusation of lying. When the memorat exists in digital form, it may simply be linked to or copied and needs no retelling as a “friend of a friend” story.

While it is rare for a memorat told for true to be proven false, it does happen. In 2012, the radio show/podcast "This American Life" retracted a story performed by Mike Daisey because it turned out to be a fabrication. Daisey’s comment on the affair highlights the importance of establishing what genre you’re in: “My mistake. The mistake that I truly regret is that I had it on your show as journalism, and it’s not journalism. It’s theater.”

The mysterious staircases in the woods

The power of the memorat as a form is particularly evident in the case of r/nosleep and the mysterious staircases in the woods. The rules of r/nosleep, a fiction board, seem almost perfectly suited to the creation of escaped legends. Stories must be “plausible” and told in the first person unless there is a good in-story reason not to (i.e., they must be pseudo-memorats). And the rules state that “everything is true here, even if it’s not”; this is a fiction board where the audience is expected to play along, rather than treating the stories like truth claims through “debunking” or “disbelief.” In other words, they make it relatively clear that this is theater, not journalism.

My favorite escaped legend from this perfectly honest fiction board has an appropriate memorat title: “I’m a Search and Rescue Officer for the US Forest Service, I have some stories to tell.” It is a set of story fragments that eventually turned into a series, about a search and rescue officer encountering, among other things, mysterious staircases deep in the woods, not attached to any structure, that her supervisors advise her to ignore. While the staircases are implied to possess spooky properties, overall it is a highly plausible, deliciously mundane image, that gets its spooky appeal in the same way “liminal spaces” do: the persistence of spaces and objects beyond their period of occupation and use, like empty, abandoned malls.

This story pretty much immediately escaped containment as fiction. A 2016 YouTube reading of the story, minus the fictional context, currently has over 11 million views, and there are many other tellings on other media. As late as August 2021, a story in the British tabloid the Mirror reported on a TikTok adaptation of the story, in which the memorat has passed into legend (“There was a story going around a couple of years ago”). Interestingly, the author of the r/nosleep staircase story reports being inspired by the work of David Paulides, a former Bigfoot researcher who pivoted to told-for-true wilderness disappearance stories about real people. Kyle Polich, writing in the Skeptical Inquirer in 2017, says that he examined a random subset of the cases Paulides classifies as spooky and found nothing unusual or inexplicable about any of them. Paulides brands himself as journalism, not theater, in the language of Mike Daisey. And Paulides does not seem to be fabricating cases out of whole cloth. Rather, he reports on actual mundane disappearances, while eliding certain details that might reveal their mundanity and adding extraneous spooky information to further set the mood. In legend formation, the details that get left out may be as important as the details that get left in.

Carbon monoxide 'hauntings'

![]() Kean Collection via Getty Images

Kean Collection via Getty Images

The staircase in the woods constitutes a kind of mundane-made-spooky story, in which a perfectly ordinary and non-paranormal phenomenon is endowed with uncanny energy. The clown sightings of 2016 are another of this kind. But this can also be inverted when the apparently paranormal or uncanny is explained away with a mechanistic solution, or the spooky-made-mundane.

An advantage the spooky-made-mundane story has over its opposite is in its more precise explanation. It fits exactly the apparently supernatural facts of the story, and it wouldn’t fit into just any story. Compare these in-story explanations to the “It Was All a Dream” cliché. This, like its relative “It Was All a Hallucination,” could explain any set of unusual facts, rather than being narrowly tailored to the facts presented. Although they render the spooky mundane, they do so in an unsatisfying, lazy way. Like “It Was Purgatory” or “Coma Dream,” they are (usually) eschewed by experienced writers. One such version is carbon monoxide poisoning.

I first encountered the “It Was All Carbon Monoxide” story from a Reddit told-for-true board, r/legaladvice, in the form of a memorat presented as a request for advice. The user, RBradbury1920, reported finding sticky notes, not in his own handwriting, around his apartment. Later he found blank notes on the outside of his door and on other doors in his building.

The user suspected his landlord of placing the notes and asked for advice dealing with the situation. However, another user came to the rescue, asking whether it might be carbon monoxide poisoning. In follow-up posts and comments, the original poster confirmed that he had been experiencing carbon monoxide poisoning, had written the mysterious notes himself, and was simply confused about the other details. Both were showered with praise and attention, and the heroic commenter was even interviewed on a told-for-true podcast.

This, like the search and rescue officer’s mysterious staircase story, appeared on Reddit in 2015. May 2015 was a difficult time for Reddit. Two years earlier, in 2013, Reddit as a collective was blamed for the misidentification of the Boston Marathon bomber as an innocent student who had committed suicide. In March of 2015, the case received more attention, as a documentary about the experiences of the innocent student’s family was released and went through a media cycle. The carbon monoxide post-it note story seemed to reaffirm that Reddit was a force for good, whatever mistakes individuals had made. In fact, the platform had saved a life!

The oldest form of this story I can find was published in Science in May 1913, by Franz Schneider Jr., a junior faculty member in the biology department of MIT. The case report is titled “An Investigation of a ‘Haunted’ House” and details the story of a family in the Back Bay who experience strange phenomena, such as tapping, feeling paralyzed, and a child being chased by a frightening figure. When the family consulted the former occupants, they found that they had also experienced strange happenings and even saw “walking apparitions.”

Of course, upon investigation by Mr. Schneider, it turned out to be a problem with the furnace, causing the family to suffer from carbon monoxide poisoning. Interestingly, Mr. Schneider appears to have lived to be 105 years old, and his obituary in the New York Times in 1993 lauds him as having “started gas companies!”

A similar but more famous account was published in 1921 by William Holland Wilmer (not the one on Wikipedia but his grandson) in the American Journal of Ophthalmology. It occurred in the fall and winter of 1912 in the house of “Mrs. H.” The details of the “haunting” mostly match those given by Mr. Schneider, except that Mrs. H relates far more, and more severe, physical symptoms: The family experiences severe headaches, fatigue, loss of appetite, weakness, and paleness as well as spooky events. For instance, Mrs. H sees herself in a mirror but doesn’t recognize it as herself at first, and this happens three times. It is unclear whether to classify some of the experiences as hallucinations or dreams, as many of them occur late at night when the experiencer is in bed and perhaps not entirely awake.

The most interesting part of this account is that it also has a hero commenter. Mrs. H’s brother-in-law visits and tells them that he’s read a story about this before and that he thinks they’re being poisoned. According to Mrs. H’s story, the idea of carbon monoxide “hauntings” was in circulation much earlier than 1912. The other case report of carbon monoxide poisoning relayed by Wilmer in the paper, in which the victim is a single man, describes no hallucinations or psychological effects but only physical symptoms. If we take Mrs. H’s account as the original, Mr. Schneider (who I believe is mentioned in the Wilmer text as “Mr. S from the university”) seems to make the narrative choice to elide the physical symptoms and only report the haunting-type phenomena, which didn’t seem to bother the family as much as the severe illness they were experiencing.

I found two other case reports of haunting-like hallucinations in carbon monoxide poisoning cases. One occurred in Taipei, Taiwan, and was published as a case report in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine in 2005. In this case, the victim reports serious physical symptoms: She was found unresponsive by her roommate, experienced numbness and cramps in her hands and feet, and was hyperventilating. But she also reported having seen a ghost while bathing.

The hero in this story is the psychiatrist, who, upon hearing about the new gas water heater the patient had purchased and that she bathed with all the windows and doors closed, immediately alerted the other doctors, and the patient was able to be treated for carbon monoxide poisoning. (Diagnostic pitfall: carbon monoxide poisoning mimicking hyperventilation syndrome, Ong, et al.) The other was published in 2012 in the journal Eye and seems to have taken place in the U.K.

The patient’s main symptoms are blurred vision, headaches, pain, and malaise. However, she also reports seeing gray patches and hearing a “whooshing” sound. The authors cite Wilmer’s case report, which is why, although the patient is not reported as attributing the symptoms to a paranormal cause, I include it here. Interestingly, this and Carrie Poppy’s telling (below) both mention a “whoosh” sound specifically. (Carbon monoxide poisoning masquerading as giant cell arteritis, Xue, et al.)

The case report, a narrative of an unusual medical case reported in a letter to a medical journal, is a type of told-for-true story that is usually highly plausible, and most case reports probably are true, at least in the main. In "Doctors’ Stories: The Narrative Structure of Medical Knowledge" (1991), Kathryn Montgomery Hunter notes that ordinary cases are rarely reported as such, as ordinary cases may be subject to other forms of study: “The criterion of narratibility ... is the unexpected, the medically interesting, the unexplained change. ... The unsurprising case sinks from narrative sight.”

While the existence of published case reports might seem to render carbon monoxide “hauntings” a mundane and common experience, it seems more likely that their very telling in case reports confirms them as highly unusual situations. Interestingly, in all cases, the physical symptoms are most prominent, and the psychological or “haunting” symptoms are secondary. When the story is abbreviated in retellings, the boring physical stuff tends to get left out, leaving only the exciting and spooky stuff.

There are two more examples of the story that I want to touch on. One seems to survive only in abbreviated retelling form, appearing in best-of threads. Here is an example of a retelling, with over 14,000 upvotes.

Someone on r/homeowners was trying to get rid of ants in his house. Tons of comments. One fellow Redditor suggested maybe there were no ants but that they were hallucinations due to carbon monoxide poisoning. OP had his house tested, and turns out there were, in fact, no ants, and he was hallucinating them due to carbon monoxide poisoning.

The story of the phantom ants illustrates that “It Was Carbon Monoxide” can explain virtually any set of events, even a mundane experience. Also, since this story is repeated in comments and was presumably originally a memorat, it has passed into formal legend territory (although it could, in fact, be totally true – we just don’t know).

The last is a highly polished memorat performed as a TED Talk by journalist Carrie Poppy, published to YouTube in March 2017. She reports experiencing symptoms including a spooky feeling of being watched, a pressure in her chest “sort of like the feeling when you get bad news,” and a persistent delusion that she was being haunted. She heard a “whoosh” sound and cried in bed every night. The sinking feeling in her chest became “physically painful,” but this polished telling gives no other physical symptoms. In fact, she reports visiting a psychiatrist, instead of a regular doctor, and in her telling, the psychiatrist refuses to prescribe her meds because she “doesn’t have schizophrenia.”

When she eventually locates her science hero and is told about carbon monoxide, she looks it up and finds the following symptoms: “pressure on your chest, auditory hallucinations (whoosh), and an unexplained feeling of dread.” I was surprised by her symptom list, as by this time I had consulted multiple symptom lists, and most lists contained overwhelmingly physical symptoms (flu-like symptoms, headache, muscle weakness, nausea, etc.). Many lists included “confusion,” but “hallucinations” were rare on lists unless the list broke down symptoms by exposure level, placing hallucinations at a very severe level of poisoning. I did find one “list of symptoms” that included hallucinations without mentioning exposure levels; it was an advertisement for a heating company, and immediately preceding the symptom list was a retelling of the Wilmer/Schneider incident.

Poppy’s telling, like that of Mr. Schneider, seems to have completely polished away any physical symptoms that might have been present. Even RBradbury1920 has to be prompted before he volunteers that he has been experiencing headaches.

The mundane carbon monoxide story

I was curious about stories of ordinary carbon monoxide poisoning, so I watched the first fifteen YouTube results for “carbon monoxide stories.” Who tells these stories? Several of them are advertisements for home security companies, and in these stories, the residents are alerted to the danger by alarms, usually before experiencing any symptoms. Some stories appear to be public service announcements published by fire departments and local government entities, featuring people telling their carbon monoxide experiences. Some are YouTubers relating stories of their own lives (told for true). In these stories, the symptoms reported are overwhelmingly physical (headaches, nausea, “felt like I was going to pass out,” etc.). One YouTuber reports difficulty writing numbers, but no one in my sample reports spooky haunting phenomena or hallucinations, even though those might make for a better story.

Despite my limited sample, I suspect that carbon monoxide-hunting stories are fairly rare. I was only able to find four published case reports of what I believe to be a total of three cases of carbon monoxide poisoning causing haunting-like phenomena, and in all cases, physical symptoms were the most prominent complaint.

Most carbon monoxide stories seem to be mundane and physical, and neither the medical literature nor YouTube lacks for these. In the transition from the actual occurrence to the “narratable” form of the story, the “haunting” type tends to lose the boring physical symptoms (limiting any informational value they might otherwise contain) and keep only the interesting psychological symptoms, whereas the mundane type keeps all the physical symptoms.

The true-false binary

![]() SOPA Images via Getty Images

SOPA Images via Getty Images

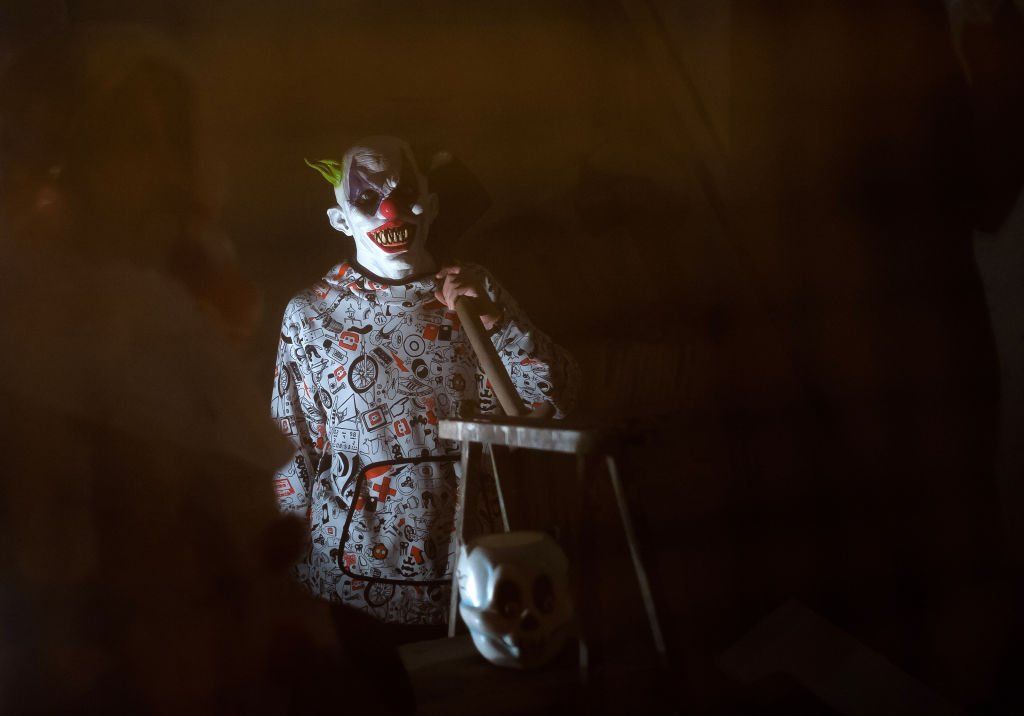

Again, all the carbon monoxide stories mentioned here may well be true. We can’t know for sure in any case. Even if the tellers later claimed to have been lying, we still wouldn’t know for sure. During the clown sightings of 2016, a filmmaker claimed responsibility for the hoax as a publicity stunt, but such a claim could well be a publicity stunt of its own. (Which is not to say that clown sightings particularly need an explanation, as people dressing up as clowns is magnificently mundane and probably a lot of fun.)

As a talking banana, it is perhaps hypocritical of me to complain that certain stories sound too good to be true. In summarizing these stories, I have myself had to leave out many details that another reader might regard as critical. I have emphasized certain details and left out others. That is true of every form of communication. The news article, the scientific paper, and especially the tweet must compress an enormous reality into a short snippet, with most details and context omitted. When a telling has been compressed and adapted to fit a particular emotional valence – spooky, interesting, important – it is serving a different communicative purpose than simply relating the truth.

Almost no story is simply true or false. I don’t even think stories can be simply “told for true” in a straightforward way. Many stories classified as urban legends have more than a grain of truth to them, and many stories accepted as true that have no bottom in reality. In all cases, the communicative purposes and the context shape the meaning that can be given to the story.

Kean Collection via Getty Images

Kean Collection via Getty Images  SOPA Images via Getty Images

SOPA Images via Getty Images

Leftist streamer Hasan Piker tried to justify Hamas’ murder of Israeli babies as 'a matter of law' and 'maybe' even 'a matter of morality.'

Leftist streamer Hasan Piker tried to justify Hamas’ murder of Israeli babies as 'a matter of law' and 'maybe' even 'a matter of morality.'