Kerosene lamps: Your escape from the sickly glare of LEDs

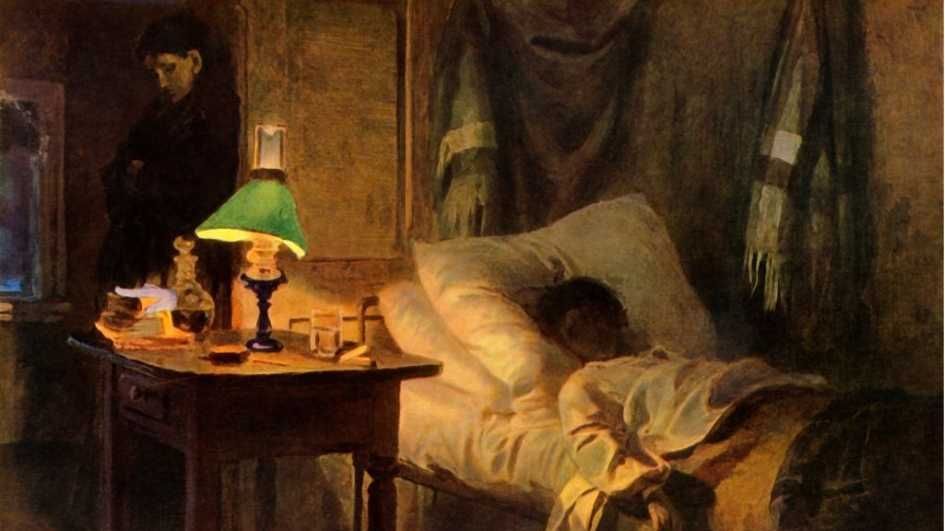

It’s my favorite time of year. When it gets cold, I fuel up four or five of the dozens of antique kerosene lamps I own. I use these to heat and light my house in winter; the charm and warmth make the cold and dark more bearable.

In past columns I’ve tried to convince you to abandon new, low-quality appliances and buy old workhorses. This time I want to persuade you to go even lower-tech and give flame light a try. You want to gather around the lamp with good people. You’ll find yourself staring into the flame, noticing the warmth it radiates (literal and metaphorical).

My center drafts have saved me during electricity outages in winter, giving enough light to work by as well as heat.

No electric lamps will make you feel this way. Some are very beautiful, of course, and the most charming use the original Edison-style incandescent filament bulbs. But they’re almost gone.

Thanks to meddling safetyist government, we live under the ghastly glow of LEDs. Before that, it was compact fluorescents. And before that, it was the sickening, flickering off-green morgue illumination of the overhead fluorescent tube, the appropriate furnishing for the inhuman Brutalist aesthetic that has infected 90% of commercial office space in the U.S. since the 1960s.

We weren’t made to live this way or light this way. We did not evolve under unnatural artificial light stripped of whole swaths of the color spectrum, drained of infrared.

We evolved by the campfire. For most of human history, the communal fire was the only source of “artificial” illumination at night. Firelight is a first cousin to sunlight, the original illumination that gave rise to all life on earth.

I’m going to give you basic tips on buying and running lamps, from simple to more complex. There’s a kind of kerosene lamp for everyone.

Sensible safety

Use common sense. You’re working with fire, and larger lamps put out a lot of heat, so be mindful that there’s plenty of clearance between the top of the chimney and the ceiling.

Keep charged fire extinguishers (you should anyway).

Yes, of course it’s possible to tip over a lamp, but in practice, it rarely happens unless you’re careless. They’re weighted to be fairly stable.

People also ask if my cats knock over the lamps. The answer is no, but you must use your own judgment because you know your animals and the layout of your house. My cats love to sleep near them for warmth and will walk on a table to get to them. But they don’t bump them. Again, you must exercise your own judgment.

No, you’re not in danger of carbon monoxide poisoning. Do you have a gas cookstove? Did you ever worry that you would get carbon monoxide poisoning from having your gas cookstove running? If you’re not afraid of your gas stove giving you carbon monoxide poisoning, there’s no physics-based reason to fear it if the flame comes from a kerosene lamp instead.

Carbon monoxide results from incomplete combustion. No combustion is 100% complete, but these lamps are burning close to it. I have been running kerosene lamps for about 15 years. They’ve never even blipped my smoke or carbon monoxide detectors.

No, the lamps won’t “suck up all the oxygen.” Your house is not hermetically sealed. The air is changing over all the time, even with your windows closed. You’re not in a pressurized submarine hull.

But “fumes,” you say. Every time you burn your favorite scented candles, you’re doing the same thing at a small scale, but no one is afraid of “fumes.” I think “fumes” is just miasma theory of disease, like how people used to falsely believe that bad odors from graveyards could transmit sickness to the living.

The only “fumes” you’re going to get with a lamp using clean kerosene are a bit of kero smell on lighting and on extinguishing. If it bothers you, take the lamp outside to light and extinguish. Remember that your ancestors right here in America all lit their homes this way, rich or poor. People weren’t dying of “fumes” or “lack of oxygen.”

The right stuff

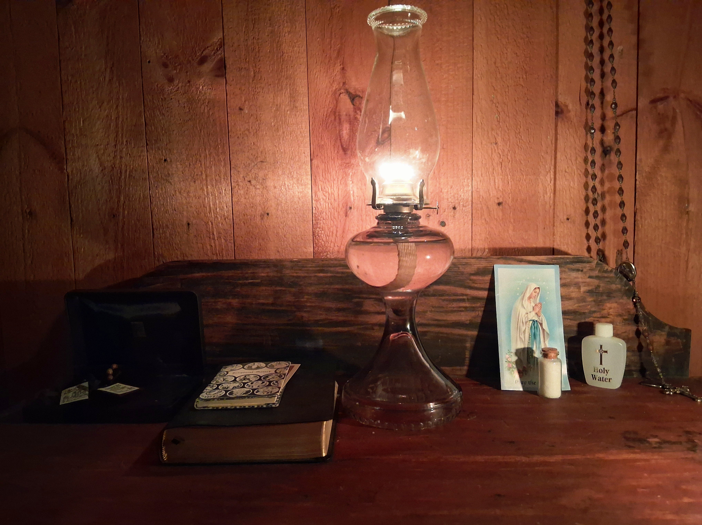

Burn only clear, undyed kerosene. Not “lamp oil.” Not “lamp fuel.” These lamps want one thing only: the specific chemical we call kerosene. It’s a petroleum distillate similar to (but much less stinky than) diesel. Kerosene is not explosive like gasoline; don’t fear an explosion.

If you’ve experienced stinky oil lamps, it’s almost certainly because someone was burning “lamp oil,” which is liquid paraffin wax. This stuff clogs up wicks, it burns half as brightly as kerosene, it can smoke, and it smells awful. Stick with clear kerosene labeled “K1” or “1K,” found in your hardware store, Tractor Supply, Walmart, and similar stores.

Level I: Flat-wick lamps

Let’s introduce you to lamps. I categorize as Level I, Level II, and Level III. We’re going to go from simplest and least expensive to more high-powered lamps. If you’re new to lamps, start with Level I, the flat-wick lamps.

Everyone knows these lamps. These are what come to mind when you hear the phrase “oil lamp.” You remember lamps just like this from "Little House on the Prairie" on television.

These are called flat-wick lamps because, you may have guessed, their wicks are flat. This is my “sewing lamp,” so called because it’s tall enough to sit on a table by you for handwork.

Consider a wall-mounted flat-wick lamp, too. These can fit in beautiful wrought-iron brackets. Mount them to a stud in the wall and enjoy the character they add to your room. Below is one of my Victorian wall-mount lamps with a mercury reflector.

Level II: Center-draft lamps

So-called “center-draft” lamps are my personal favorite, and I recommend that you get at least one of them. They draw air from a central tube in the middle of the burner. Unlike flat-wick lamps, center-draft lamps have a round wick. They're larger than most flat-wick lamps, so they put out about three times the light and heat of a basic lamp.

One center-draft lamp is enough to heat a medium-sized room, and you can cook over it in a pinch by rigging up a trivet. My center-draft lamps have saved me during electricity outages in winter, giving enough light to work by as well as heat. They’re essential equipment for anyone who is into prepping for emergencies. Plastic electronic LED lights with fancy solar panels can’t hold a candle to the rugged practicality and versatility of these.

Here’s my favorite, the “New Juno” model, made from 1886 to about 1915.

Any center-draft lamp is a good buy as long as it has all the parts necessary for operation (be sure it has a flame spreader). At the end of this article, I’ll link to businesses that specialize in advice and replacement parts. Do a little bit of reading, and you’ll learn everything you need to know before you buy.

Level III: The magical Aladdin lamp

Technology becomes as fun as it will ever get when one tech is declining as another rises. The old tech has to compete with the new, so the old tech gets refined to its highest potential just before it becomes obsolete.

That’s the Aladdin lamp. “Aladdin” is a brand name, not a generic type. These lamps are the zenith of kerosene technology that was competing with new electric light. These are mantle lamps. What does that mean? Bring to mind the Coleman lanterns you remember from camping. The ones that hiss and put out a very bright light. Those are mantle lamps too.

Aladdin lamps are mantle lamps, but instead of burning compressed gas, they burn kerosene.

In mantle lamps, the light does not come from the flame. The flame is used to heat the incandescent mantle. This is a thin, delicate mesh impregnated with rare-earths and mineral salts. These elements glow white-hot under heat. This is how the Aladdin lamp can produce a light that matches modern electric bulb output.

They are wonderful devices, and I have a few, but they are more finicky. They need a mantle, and you have to be very careful to keep the wick absolutely level, or you’ll get flame spikes that leave black carbon deposits on your mantle. The solution is to turn the flame low and burn off the carbon slowly.

Here’s my 1936 Aladdin Model B in green Corinthian glass:

Hopefully this has tempted you to get your first kerosene lamp. There are some dependable businesses run by people who love these lamps and know everything about them. Most breakable and replaceable parts like the glass chimneys and the wicks are still made and readily available from these purveyors and others.

Nobody knows more about lamps, and nobody has a wider selection of wicks, chimneys, diagrams, and how-to articles, than Miles Stair on the West Coast of the U.S. Go to his site first whenever you have a question.

Woody Kirkman of Kirkman Lanterns manufactures and sells quality reproduction lamps and replacement parts for antiques. You have likely seen his work in period films and at Disney parks and like. He is often hired to supply kerosene and gas lighting fixtures for movies and TV and for theme parks.

Gather those you love around you, and light your lamp.

Caroline Seidel/Getty Images

Caroline Seidel/Getty Images

Flip City Magazine

Flip City Magazine Flip City Magazine

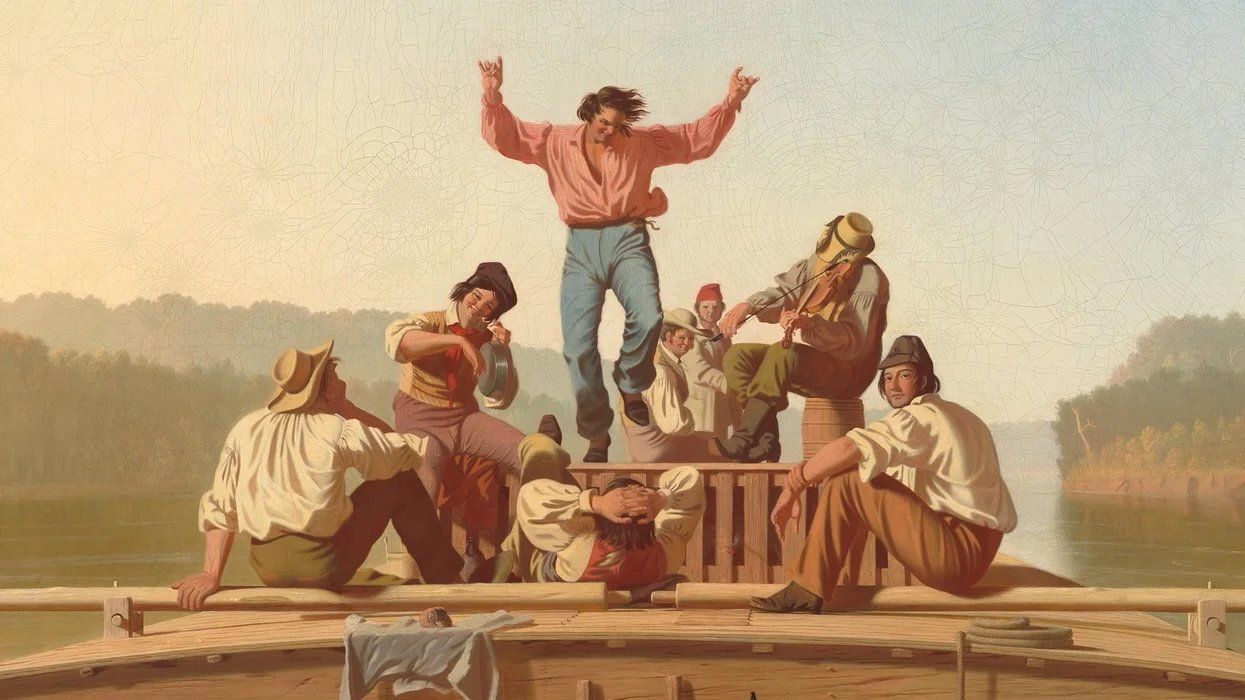

Flip City Magazine George Caleb Bingham: The Jolly Flatboatmen (1846) | National Gallery of Art

George Caleb Bingham: The Jolly Flatboatmen (1846) | National Gallery of Art

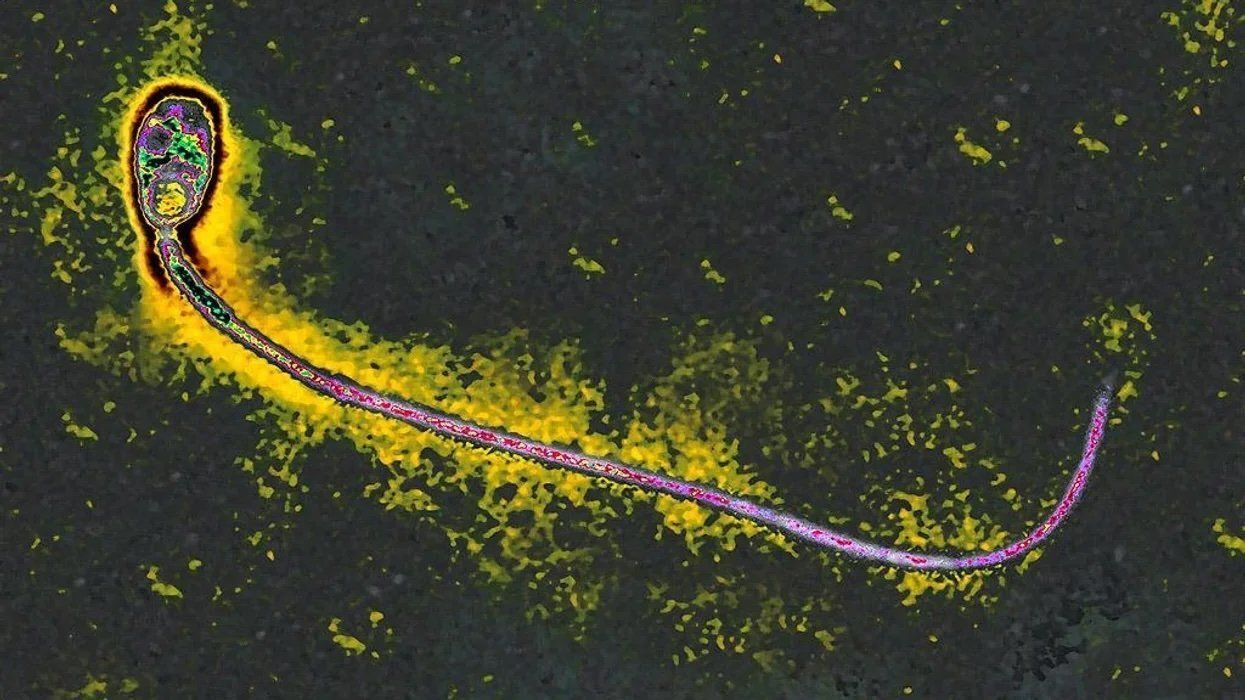

BSIP/UIG via Getty Images

BSIP/UIG via Getty Images Kindred Harvest

Kindred Harvest

Photo by Rich Sugg/Kansas City Star/Tribune News Service via Getty Image

Photo by Rich Sugg/Kansas City Star/Tribune News Service via Getty Image

Blaze Media

Blaze Media Acorn Bluff Farms

Acorn Bluff Farms

Delbert Shoopman/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images

Delbert Shoopman/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images Selo Olive

Selo Olive

Natalie Behring/Getty Images

Natalie Behring/Getty Images