Louis Pasteur: Man of science who tamed rabies

A little over three years ago, Anthony Fauci went on MSNBC to address critics of his COVID policies. What made the attacks on him especially "dangerous," the doctor cautioned, was that they were actually "attacks on science."

These days, of course, Fauci is eager to distance himself from the dubious "science" he once championed, be it public mask mandates, school shutdowns, or confident statements that the virus did not originate from a lab leak. It should be clear by now — if it wasn't before — that "science" is just as susceptible to superstition and groupthink as any human endeavor. Contradicting conventional wisdom can entail real risk.

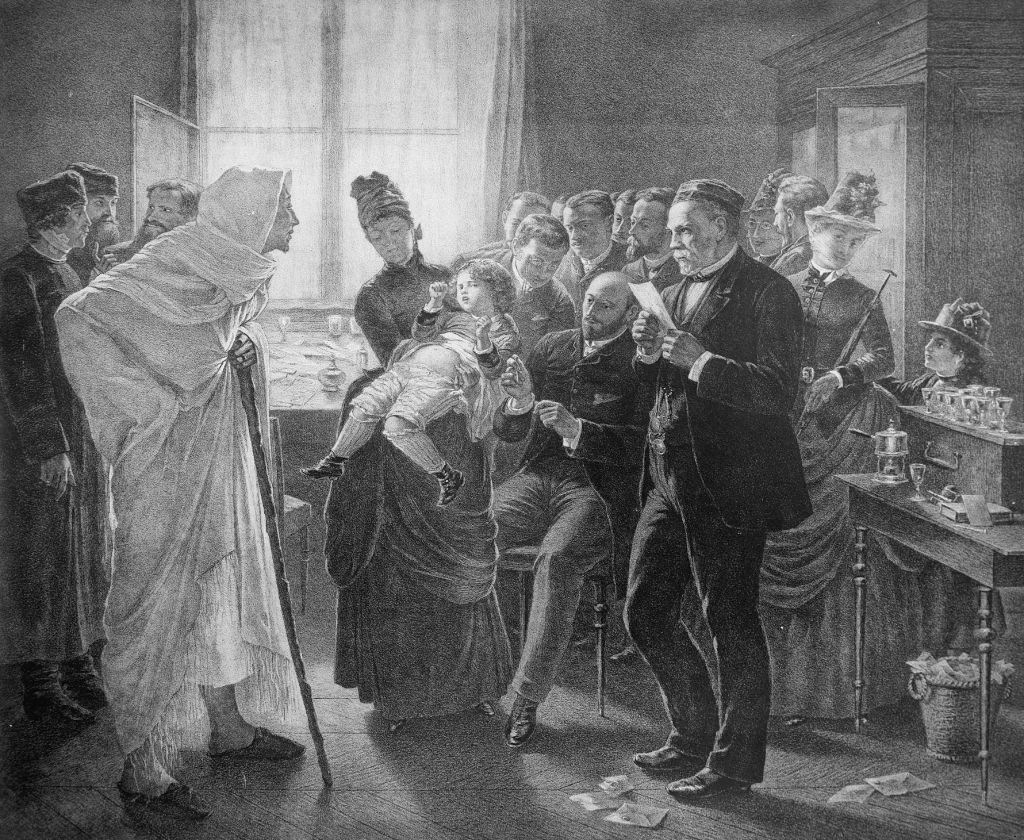

Had his rabies vaccine not worked on 9-year-old Joseph Meister, French microbiologist Louis Pasteur could very well have ended his career in disgrace and in prison. Not only did Pasteur have no proof that his vaccine would work on humans, he had no medical license allowing him to administer it.

By that point in his career, Pasteur was already quite successful and had no reason to rush development on his cure for rabies. In the 1860s, he had disproved the conventional wisdom that illness and pests who spread it arose spontaneously from nonliving matter by showing that invisible bacteria were to blame. Identifying the enemy allowed the development of effective ways to stop it: among them the well-known process of destroying microbes in beer and milk that takes Pasteur's name. He also pioneered the process of artificially weakening bacilli in order to use them in vaccines.

But the boy's mother was desperate for any chance at saving her son from a hideously painful death. For some idea of what he faced, we can turn to this contemporary case study:

On the 17th of June, 1981 an Englishwoman traveling in India was bitten on the leg by a dog. The wound was immediately cleansed by her husband using whisky as an antiseptic. She later attended a local clinic where the wound was again washed and packed with antiseptic powder. The woman returned to England in July and the wound was redressed in her local hospital. By the middle of August she became constantly tired and complained of aches and shooting pains in the back. She was anxious and depressed, and appeared to catch her breath when trying to drink. By the 19th of August she found it impossible to drink more than a few sips. She could not bear the touch of the wind or her hair on her face and had moments of apparent terror. The following day she was confused, hallucinating, incontinent of urine and quite unable to eat or drink. For the next two days she was intermittently hallucinating and screaming with terror until she collapsed and had a cardiac arrest. Although she was resuscitated in the ambulance whilst being carried to intensive care, she died two days later, on 24th of August 1981, without recovering consciousness.

So, Pasteur summoned some medical colleagues and proceeded to put his reputation on the line. As he wrote in his notebook: “The child’s death appeared inevitable. I decided not without acute and harrowing anxiety, as may be imagined, to apply to Joseph Meister the method which I had found consistently successful with dogs.”

Whatever mixture of charity and ambition prompted Pasteur to make this audacious bet, it paid off. Meister fully recovered and lived into his 60s, and rabies was no longer a death sentence.