![]()

Atheism is a really boring ideology for storytelling.

There’s no God, no morality, and no meaning. Everything is an accident, and we can take only the most superficial material interpretations possible. This kills all storytelling except the most nihilistic genres.

And this presents a problem because nihilism is well ... boring. It can’t sustain a narrative. People seek meaning. People seek purpose. It’s not just instinctual. It’s necessary. So what do atheists do? They take old religious meanings and filter them through an atheist lens.

We can talk about humanity’s grand destiny all day, but the future of humanity is not something particularly inspiring to the guy working nine to five.

So what are we going to do? Look at Ridley Scott's 2012 "Alien" prequel, "Prometheus." God is real but he’s an alien. Creation has a purpose, but it’s evolution.

The redemption of mankind is through our IQ and eventual ascension into godhood. It’s all the same beats except through atheistic and materialistic virtues (or subversions). The story is just as religious, but it’s now bent for a really shallow religion.

No atheists on starships

These tropes are so ubiquitous that we take them as given assumptions for the sci-fi genre, but they’re just recycled ideas (mostly from Christianity). And so atheists steal their depth from truth that rightfully belongs to religion. They just pretend it’s more “scientific.”

Deliberate design is a completely pseudo-scientific concept (according to atheists). There’s no evidence for it, and the mainstream consensus is that life was a cosmic accident. But you can’t say anything about a cosmic accident. You can only shrug your shoulders at it.

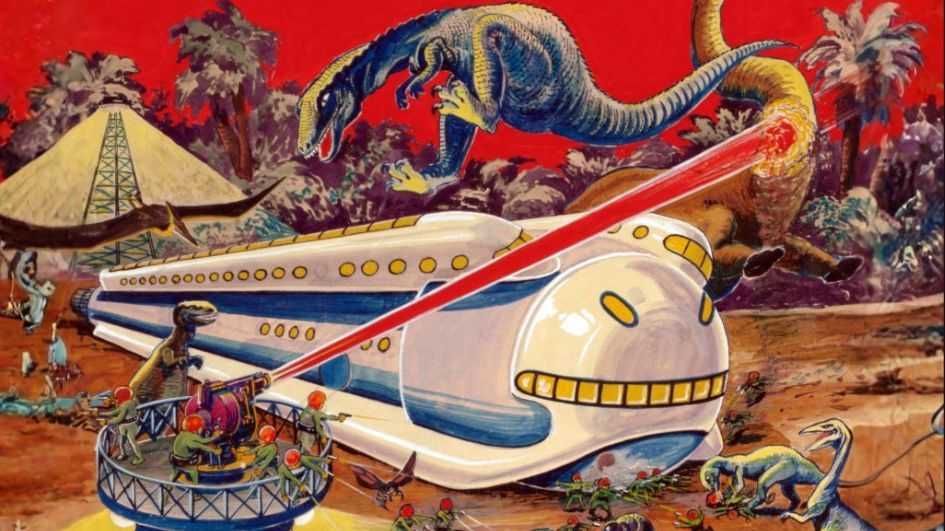

Nearly every sci-fi story has some form of deliberate design, they just replace the Christian God with aliens or whatever. Even though it is often atheists writing the stories, they reinsert this completely pseudo-scientific concept. Why? Because atheism is really boring.

Here’s a fun drinking game: Take a shot whenever you see a story treating evolution as a series of progressing stages. This is a completely nonsense read of evolution. There’s no moral component to evolution. It’s just adaption to environment. There’s no end goal.

But nearly every sci-fi story treats it as such. It gets to the point where it’s straight disinformation. Every time the story is about mankind’s rise from apes to the stars when that’s utterly irrelevant from an atheist perspective. Why? Because atheism is really boring.

Mankind's end goal is something like "Star Trek’s" Federation. But why is that a good thing? Why is space liberalism the default? What is morality based on? Where are we going? Who’s to say the Klingons don’t have it right? Why are there good guys and bad guys?

“But it’s all just fiction!” I hear you say. “It doesn’t matter.” But fiction isn’t nonsense. It’s an outlining of ideals, principles. Writers don’t just write random chaos. They write an extension of their worldview. Why then don’t we have properly atheist stories?

A properly atheist story would be completely materialistic, accidental, with absolutely no meaning or morality that has whatever intrigue being completely incidental to the plot. Now I have to ask: Doesn’t that sound like a really boring story?

How, then, did professed atheists like Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, and Gene Roddenberry create the the archetypal myths that define the modern world?

The mystics of progressivism

By the 1960s, progressivism had reached a new ascendancy. Fueled by the unparalleled wealth that came with a modern economy, millions were lifted into new, luxurious lifestyles. Now was the time to put aside the ignorance of religion and finally embrace the freedoms offered by a world liberated from Christianity.

It isn’t hard to understand how so many fell for the deception. Things were getting better and better. Technology was improving, and more importantly, accelerating. The Soviet Union was an existential threat, yes. However, too many had already seen the miracle of science, and it seemed a better horse to back than spiritually weakened priests who were quickly conceding to the liberalism’s demands.

But with any new religion, there has to be a story, and the story science told wasn’t so flattering. Men had gone from sons of God to sons of apes. Salvation was a lie, and death was the end. There was no justice in the world, and mercy was just the delusion of fools. Man was a small being in a cold universe. The only thing modern men could be comforted by was his own increasing material comfort.

That’s not a story anyone wants to hear. And it’s certainly not a story anyone wants to tell. While abject nihilism has always had its place in literature, it rightfully has a small audience. Nihilism has nothing that could sustain a city, much less a nation.

Reason and science needed romance. It needed adventure and a destiny. Without these things, it was a boring, uninspiring philosophy. Writers (good ones anyway) instinctively shy away from boring. Better to be dead than boring. If there is a victory, it has to be a glorious triumph. If it is a defeat, it has to be a last stand. And if it is banal, then it has to be the most shuddering and teeth-clenching banality of all.

But the sci-fi writers of the 1960s and later were capable of far more than banality. They knew how to tell stories, and they (unconsciously or otherwise) slipped that dreaded irrationality and religious ignorance back into their fiction.

'2001: A Space Odyssey'

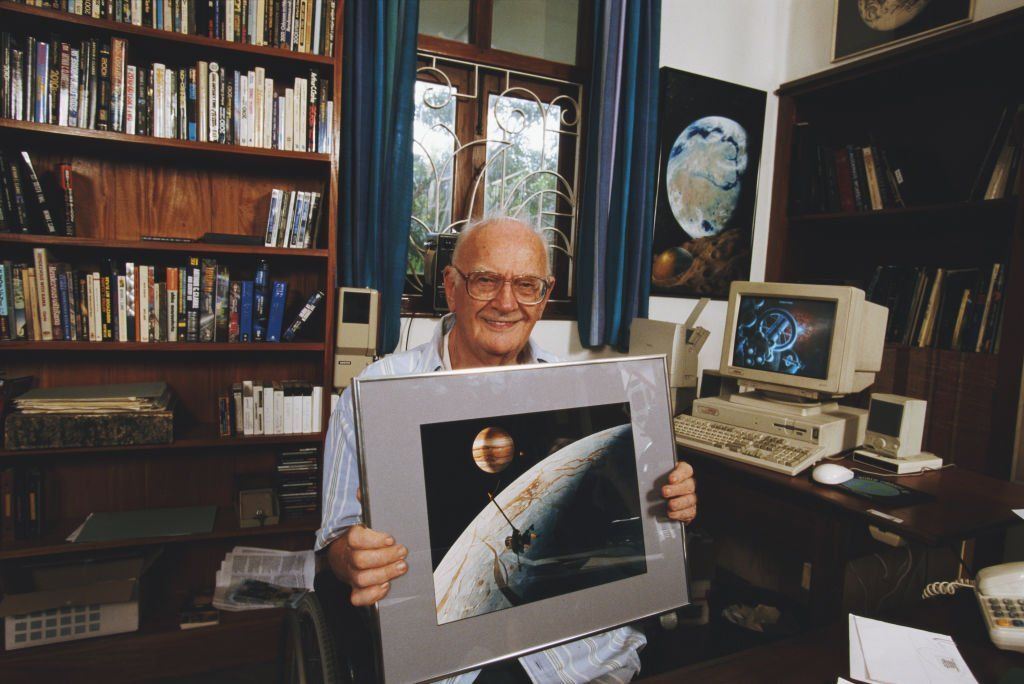

We’ll start with what I consider to be the quintessential story of progressivism. "2001: A Space Odyssey" was written in 1968 by Arthur C. Clarke (one of the Big Three sci-fi authors).

The original novel frames evolution not as random mutation guided by arbitrary natural selection but rather as a series of stages, with each improving and progressing from the last. Guided by the hands of an intelligence, men are the products of a consciousness far beyond our comprehension.

From a purely scientific standpoint, this is complete hogwash. But from a storyteller’s perspective, this is gold. Men are no longer an accident of cosmic forces. Suddenly, we have a destiny again.

There’s a conflict of tug and pull. We are going somewhere and we (at least to this incomprehensible intelligence) matter. We may be apes, but we have the potential to be something more. Can we realize this destiny?

![]() Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images

Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images

You’ll notice that God is back in the equation. Except this god is a surprisingly hollow one compared to the Christian God. This one makes no demands or moral rules upon humanity. This one does not care about the suffering of the life it created. This one wants little to do with humanity except when it achieves a sufficient stage of intelligence.

Make no mistake, this is a despotic and cruel god. But, it is also a god fit for rationalism. Could we be the products of unimaginable forces? Maybe. Nobody wants to believe this was all an accident. And while this god is empty, it is sufficient food for the poets and artists. So long as nobody makes any moral demands beyond the current zeitgeist, it is a harmless idea for scholars to speculate and pine about.

This idea of incorporating evolution into the narrative of progress and a distant, indistinct entity in God’s place is a common thread throughout all of sci-fi. And it doesn’t even have to be an indistinct entity.

In the movie "Contact," this role is occupied by a galactic community that judges humanity worthy to join them after a set time has passed. But do you know the kicker? Humanity is considered at all because we sent out some radio signals. That’s ... depressing.

But there is another problem. What of the individual’s place in all of this? We can talk about humanity’s grand destiny all day, but the future of humanity is not something particularly inspiring to the guy working nine to five. Yay, we’re in the transitionary period where everything is still kinda awful, but our descendants will get to enjoy space utopia.

Flawed 'Foundation'

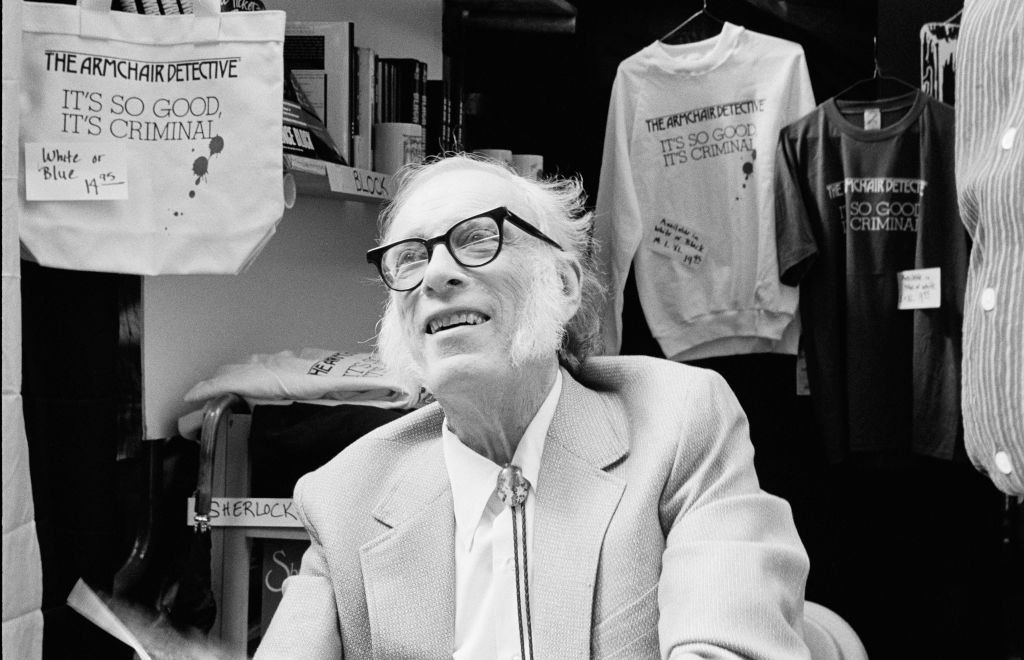

This question is not answered but sidestepped paradoxically. Another of the Big Three, Isaac Asimov, showcases this bait and switch quite well in his magnum opus, "Foundation." This epic spans the collapse of a galactic empire. Hari Seldon has devised a new science called psychohistory, which charts the course of societies. He goes to set up Foundation, which will be a light of science and knowledge in the coming Dark Ages and eventually bring back the empire.

![]() Rita Barros/Getty Images

Rita Barros/Getty Images

This is a story that spans centuries. Its whole premise is charting the course of history. And psychohistory is not a science that is kind to individuals. It says what determines the course of history are large-scale incentives and institutional rot. We are but numbers on a spreadsheet encompassing billions of worlds, and the greater part of humanity is accounted for in the margins.

But how did Isaac Asimov write this story? Well, he didn’t, at least not in the way he thought. A third of the first book follows a shrewd politician named Salvor Hardin as he outmaneuvers factions within Foundation. He eventually consolidates the society and neighboring kingdoms into a religious theocracy. Particularly, he accomplishes this through a clever ruse by outfitting enemy fleets with a kill-switch and faking it as divine power.

14-year-old me put down the book at the moment and asked, “OK, but what if there wasn’t Salvor Hardin?” There is some argument for the Second Foundation and Seldon predicting the rise of great men, but individuals are precisely the antithesis of psychohistory.

You’ll find in each section of Isaac Asimov’s magnum opus there are great men of history. There are people who rise above the paradigm and set the trends of the coming future. And it is not just captains of industry or conniving warlords. Even small people have a huge impact on galactic affairs. The Mule (a mutant with telepathic powers) lost because he fell in love with a normal woman.

Sci-fi is full of these characters. One moment they are but insignificant specks, the next they are upending everything. In this, you see a paradox which is played whenever the narrative is convenient for it. Humanity is vast and the individual has no power or the individual leads the revolution and remakes society.

I’m not saying this is done deliberately (though it probably certainly happened at some stage). However, progress needed a place for the individual, if only because storytellers demanded it so. You cannot tell a good story without people whose actions matter.

Stories need heroes and villains, otherwise, you have no story at all. It may go completely against the rational point of view, which says people are utterly insignificant, but can’t we just pretend that we are?

The final component of this narrative is a vision of what is trying to be achieved. The stage is set. We have our gods and demons, heroes and villains. For what shall be the contest? Well, the answer varies depending upon who you ask.

The final frontier?

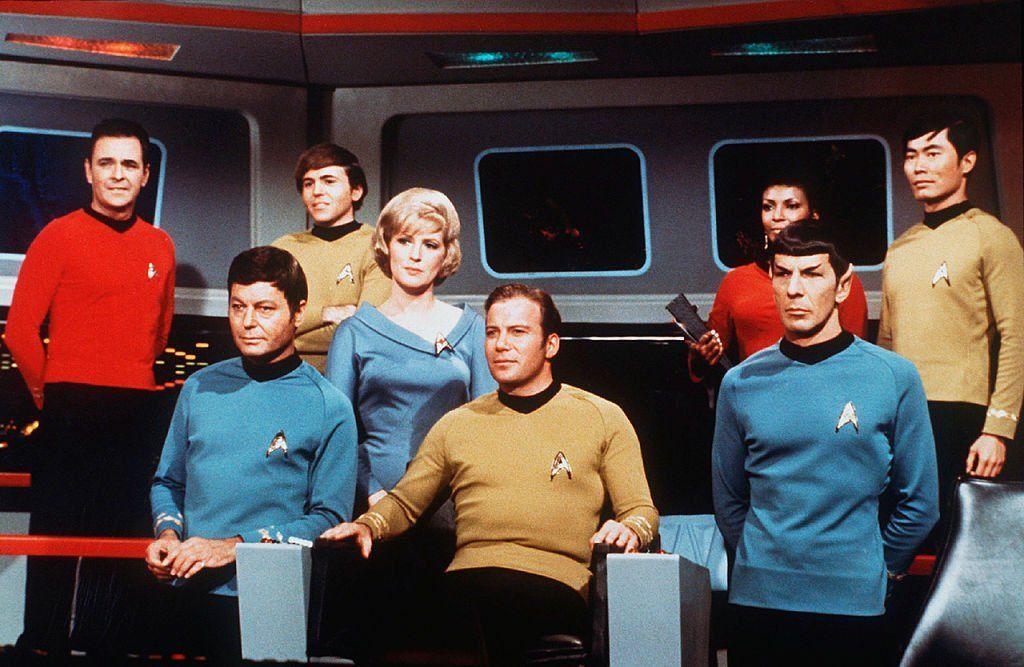

Gene Roddenberry’s vision in "Star Trek" is of a space-traveling humanity for which all material wants were satisfied. Thankfully, the galaxy was filled with different peoples and aliens to meet. Otherwise, his stories would be fairly boring. Of course, that is the least of his world-building troubles. "Star Trek" does not stand up to even the most cursory scrutiny.

![]() Ron Galella, Ltd./Getty Images

Ron Galella, Ltd./Getty Images

However, I don’t think progress was promising material utopia. At least, that wasn’t what people wanted. Utopia is a nice political aim, but I suspect what really captivated the audience was the prospect of an endless adventure.

What is mankind now fighting for? Ironically, the soldiers of progress want the world to go back as it once was, where the horizon was an unexplored frontier. In the 16th century, men put themselves on little boats and crossed oceans for adventure.

But space is too vast an ocean and our boats too tiny to cross. I have seen many futurists on the internet, and the dream of space travel is admittedly an intoxicating one. It tends to fill your thoughts as you work retail. I know it did for me.

In the imagination of many, humanity was just at its short adolescent stage. Once it stepped into the stars, the fun would begin again. Again, this goes against all science. The galaxy so far has been silent, and I think it’s time we begin to accept that alien life, if it does exist, is so far away as to be inaccessible.

Digital heaven

Space is out. But what about computers? "Neuromancer" by William Gibson was released in 1984. A little later than the 1960s, but it’s still a foundational text. Perhaps the future we’re fighting for is a simulation? Of course, I wouldn’t want to live in the world of "Neuromancer," but the dream of uploading your mind is an enticing one. What if your life could be a video game?

Suppose you could do it. Suppose I could turn you into a program and put you in a simulation. Would your life be better than what you have now? For those advocating for this future, most seem to skip that step.

Let’s take a look at the modern day. Are our lives really better with what digitization has already accomplished? Everyone agrees social media is a plague on humanity, yet why are so many pushing to trap themselves on what would be the ultimate social media platform?

You’ll again notice we’ve ditched reason yet again for a digital version of heaven. And our future is so much more enlightened than religious notions of an afterlife. We’ve taken salvation and commercialized it. Your eternal soul will be bought with the U.S. dollar.

But putting all that aside, why do these stories matter? These stories are all fiction. They are nothing to be taken seriously. I can already hear the cry that this all has nothing to do with the actual expectations people had for the future. Had I brought "2001: A Space Odyssey" into an academic debate on industrialization, I would’ve been laughed out of the room.

However, people do not tell stories just for mindless amusement. In them are the beliefs of a people. More than just hopes and dreams, stories are a reflection of the world as we see it. And in these stories I have listed, you see the beliefs of the people writing them.

You see their gods and devils, their heroes and villains, and the reality they want to make happen. Stories are a look at where we are and where we are going. And most importantly, stories are a confession of faith.

Did Arthur C. Clarke believe in monoliths that uplifted humanity? No. But he certainly believed in the god that made them.

A version of this essay originally appeared on the "Trantor Publishing" Substack

Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images

Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images Rita Barros/Getty Images

Rita Barros/Getty Images Ron Galella, Ltd./Getty Images

Ron Galella, Ltd./Getty Images

CBS Photo Archive/Getty

CBS Photo Archive/Getty Bob Penn/getty

Bob Penn/getty

Before Disney made Star Wars gay, it was just a poorly written cash grab meant to sell merchandise to dweebs.

Before Disney made Star Wars gay, it was just a poorly written cash grab meant to sell merchandise to dweebs.

CBS Photo Archive

CBS Photo Archive