Do you follow a diluted Jesus — or the full-strength one?

One of the most revealing features of modern Christianity — across Catholic, Protestant, and nondenominational churches alike — is how Jesus is so often presented: gentle, affirming, and above all reassuring. He is described primarily as the “Prince of Peace,” a title that appears only once in scripture (Isaiah 9:6), or reduced to a generalized ethic of niceness often summarized as “Jesus is love.”

The problem is not that these ideas are false. It is that they are radically incomplete.

Jesus prays for His followers, not for the world as such. He commands love of neighbor, but He never pretends that truth and allegiance are optional.

Scripture presents God as merciful, gracious, and abundant in goodness and truth (Exodus 34:6), but the same passage insists that He “will by no means clear the guilty.” Love, in the biblical sense, is inseparable from justice.

When Jesus commands His disciples to love one another, the apostle Paul clarifies what this means: to fulfill the law and do no harm to one’s neighbor (Romans 13:8-10). Love is not affirmation of wrongdoing; it is obedience to God’s moral order.

This distinction was not always obvious to me.

Scriptural reckoning

For much of my life, I was a Christian in name only — attending church, absorbing familiar slogans, and assuming that the moral core of Christianity consisted of kindness paired with a firm prohibition against judgment or righteous anger. That changed four years ago when I began reading scripture seriously, first through a Jewish translation of the Old Testament and later through a King James Study Bible in weekly study with a close friend.

We made a simple but demanding commitment: start at Genesis and read every verse, in order, without skipping the difficult passages. We are now in Matthew 6. This approach differs sharply from curated reading plans that promise familiarity with the Bible while quietly filtering out the parts that unsettle modern sensibilities.

Reading scripture this way forces a reckoning.

Anger management

Consider Matthew 5:22, where Jesus warns against being angry with one’s brother “without cause” — a qualifying phrase absent from many modern translations. That distinction matters. Without it, the verse suggests that all anger is sinful. With it, scripture acknowledges a truth borne out repeatedly: Anger can be justifiable, but it must be governed.

Jesus Himself demonstrates this. He overturns tables in the Temple (Matthew 21:12). He rebukes religious leaders sharply. He experiences betrayal, grief, and indignation — yet never loses control. The lesson is not emotional suppression, but moral discipline.

Reading the King James Bible makes these tensions impossible to ignore. Its language is austere and elevated, but more importantly, it preserves a view of humanity that allows for courage, judgment, and resolve alongside mercy. This stands in contrast to many modern ecclesial presentations of Christ, which portray Him almost exclusively as a comforting presence whose primary concern is emotional reassurance.

RELATED: The day I preached Christ in jail — and everything changed

No more Mr. Nice Guy

But Jesus explicitly rejects this reduction. In Matthew 5:17-20, He states plainly that He did not come to abolish the law or the prophets, but to fulfill them. The New Testament does not replace the Old; it completes it. The Old Testament establishes the moral and civilizational framework. The New Testament builds the interpersonal life of faith upon it.

Jesus is eternal (John 8:58), one with the Father and the Spirit (John 14). He is not absent from the demanding and often terrifying episodes of Israel’s history. The same Christ who calls sinners to repentance is present when God judges nations, disciplines His people, and establishes His covenant through struggle and sacrifice.

This continuity matters because it exposes the weakness of a Christianity that treats faith primarily as therapy. Churches shaped around likability and marketability inevitably soften doctrine. Hard truths drive people away; reassurance fills seats. The result is a faith that speaks endlessly about peace while avoiding the cost of discipleship.

A pastor at my church recently put it well: It is better to hold a narrow theology — one that insists scripture means what it says — and to extend fellowship generously to those who submit to it, than to hold a broad theology that can be made to say anything and therefore demands nothing. Jesus prays for His followers, not for the world as such (John 17). He commands love of neighbor, but He never pretends that truth and allegiance are optional.

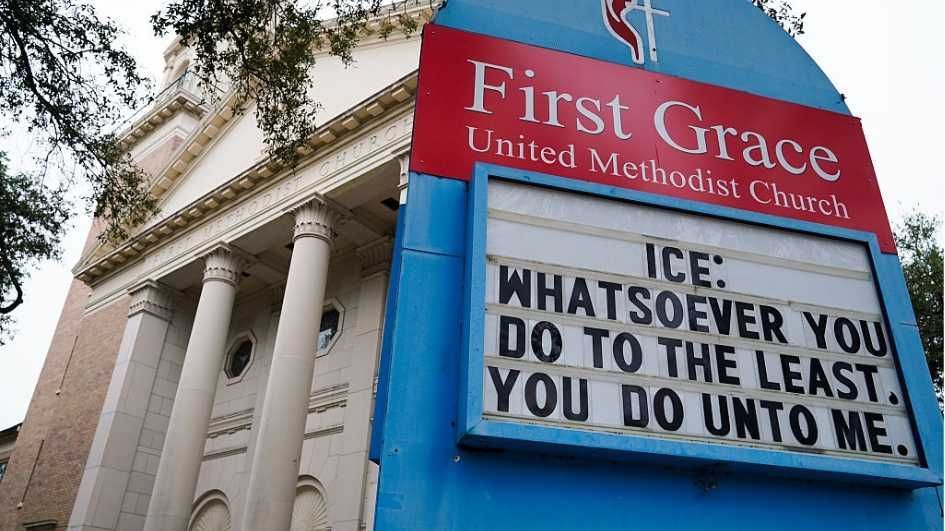

This is why Jesus’ own words about conflict are so often ignored. In Luke 22:36, He tells His disciples to prepare themselves, even to the point of acquiring swords. The passage is complex and easily abused, but its presence alone undermines the notion that Jesus preached passive moral disarmament. Scripture consistently portrays a God who calls His people to vigilance, readiness, and courage — spiritual first, but never abstracted from the real world.

Cross before comfort

Many of Jesus’ parables involve kings, landowners, or rulers — figures of authority, stewardship, and judgment. The Parable of the Ten Minas in Luke 19 is especially unsettling. There Jesus depicts a king rejected by his people, fully aware of their hatred, and describes the fate rebellion would merit if this were a worldly kingdom. The point is not to license violence, but to make unmistakably clear that rejection of Christ is not morally neutral.

Modern Christianity often flinches at this clarity. It prefers a Jesus who reassures rather than commands, who affirms rather than judges. But scripture presents something sterner and more demanding. Jesus does not seek universal approval. He seeks faithfulness. He does not promise comfort. He promises a cross.

As the late Voddie Baucham frequently observed, the cross is not a symbol of tolerance; it is a declaration of war against sin.

The question Christianity ultimately poses is not whether Jesus is kind — He is — but whether He is Lord. And if He is, discipleship is not a matter of sentiment, but allegiance.

Washington Post/Getty Images

Washington Post/Getty Images

Photo by ANOEK DE GROOT/AFP via Getty Images

Photo by ANOEK DE GROOT/AFP via Getty Images

Scott Adams in 2002. Phil Velasquez/Chicago Tribune/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

Scott Adams in 2002. Phil Velasquez/Chicago Tribune/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

Heritage Images/Getty Images

Heritage Images/Getty Images

Photo by Masrio Tomassetti - Vatican Media via Vatican Pool/Getty Images

Photo by Masrio Tomassetti - Vatican Media via Vatican Pool/Getty Images

Photo by Heritage Images/Getty Images

Photo by Heritage Images/Getty Images

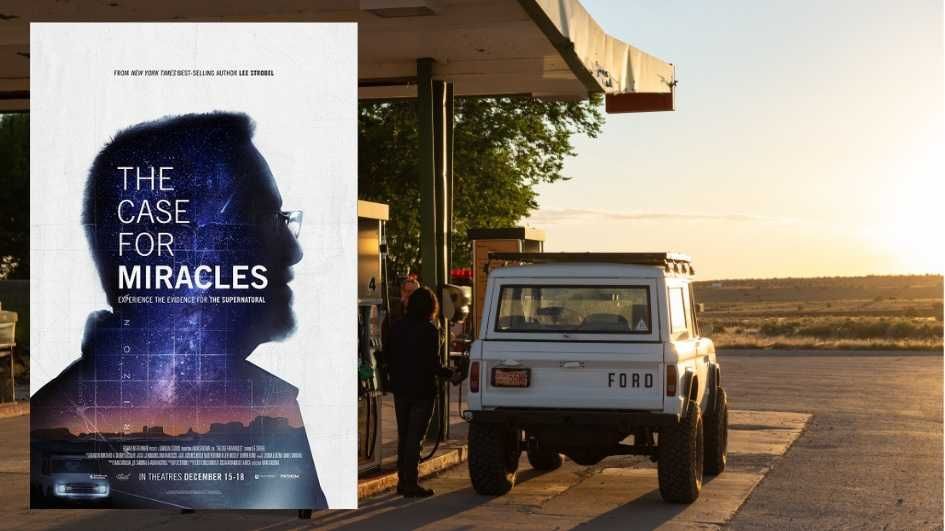

Blaze Media

Blaze Media

Russell Moccasin

Russell Moccasin