Investigative journalist warns: We are being ‘harvested’ for a posthuman future

Tech developers have sold us artificial intelligence as the ultimate tool for human progress and convenience. But people would be wise to ask, “What’s the catch?”

In a recent interview with Glenn Beck, investigative journalist Whitney Webb answered that question. What she reveals is bone-chilling.

“They want to harvest us for data. … They want to use us as bootloaders for their digital intelligence. They can't continue to improve and feed the AI without us doing it for them,” she says.

In other words, the future of AI depends on human experimentation.

AI users have been shackled by comfort and convenience. Without even realizing it, they’ve agreed to be put in a “digital prison without walls,” says Webb.

She advises those who care about their freedom to “actively build alternatives,” like “local resilient networks that don't depend on [AI] infrastructure,” and to seek “open-source alternatives to a lot of the Big Tech platforms out there.”

If we don’t start pushing back (and soon), we will be launched into a “posthuman future,” she warns.

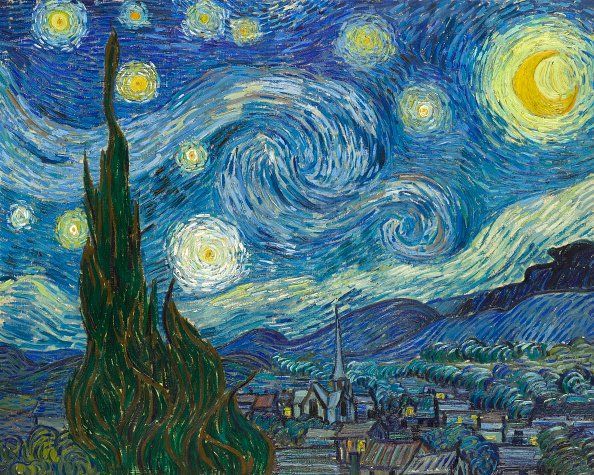

This elitist initiative to eradicate our humanity is evident in that much of AI is targeted toward art, music, and writing — the very things that make us human.

“These are the things that we're being told to outsource to artificial intelligence,” says Webb.

“So what's going to be left for us when we outsource this all to AI? Will we allow ourselves to be cognitively diminished to the point that we can't even create any more? What kind of humans are we at that point?” she asks.

Another act of rebellion we all must commit is to refuse to relinquish creative work to AI and to raise children who are “anchored in the real world,” meaning they can paint and draw better than they can navigate a tablet.

Webb warns that parents must be intentional if they want to guard their families against the encroachment of the digital age, because techno-dependency, especially when it comes to children, is a pillar in elites’ sinister plan to push us into posthumanism.

“There's these efforts to have domestic robots in the house. A lot of the ads show young children developing emotional relationships with these robots, saying, ‘I love you.’ … That is not good,” says Webb.

If you need even more evidence that the Big Tech world is against your children, Webb reveals that many of the top figures in the tech industry were friends with Jeffery Epstein, a convicted pedophile.

“Do you want to trust those people to program stuff that's around your kids?” she asks.

She acknowledges that in the modern era, it’s exceedingly difficult to raise children without the help of technology and to set parameters for ourselves. That’s why so many people don’t bother with it. But they’ve fallen prey to the nefarious plot that undergirds the entire posthumanist movement: Create a society that worships convenience and comfort.

“The pull of AI is for us to be passive and do nothing and just let it wash over us,” says Webb.

“If we're not focused on the things that we like to create and that we like to do … we will recede, and that is how the posthuman future will happen.”

To hear more, watch the full interview above.

Want more from Glenn Beck?

To enjoy more of Glenn’s masterful storytelling, thought-provoking analysis, and uncanny ability to make sense of the chaos, subscribe to BlazeTV — the largest multi-platform network of voices who love America, defend the Constitution, and live the American dream.