This one 'SpongeBob' episode explains what’s wrong with tech today

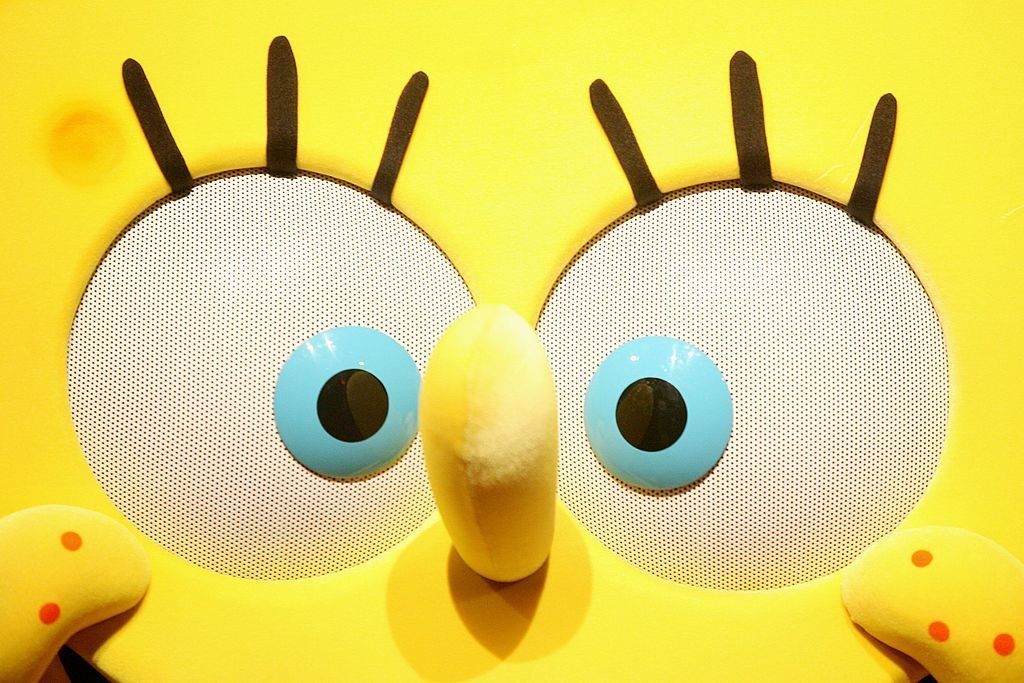

The best season of a TV show is frequently the first season, and as true "SpongeBob SquarePants" lovers know, there’s no substitute for Season One. Before the lunch boxes, before the movies, before the relentless IP exploitation, there was a simple cartoon, and in its simplicity was often to be found the simple yet expansive wisdom of the timeless fable.

Of course, in times like these, the timeless is especially timely. Technology has thoroughly warped our experience of our given chronology, scrambling and blurring legacy expectations around life span, generations, family formation, commutes, seasons, and so much more.

But as SpongeBob reminds us, instead of becoming gods, we’ll be freakish mutants unfit for either world, mortal or godly. The task falls to us mere mortals to have another idea … one far more humble than the posthuman temptation allows: Carry on with our human lives, but in ways that ensure the heavenly Spirit may, and does, move within and among us.

Nostalgia, futurism, and “the moment” compete for our loyalty and our attention, and our imaginations groan with mingled hope and fear toward the prospect of our collective techno-transformation into something that seems at once more and less than human.

So — "SpongeBob," Season One, Episode 19b, affectionately known as “Neptune’s Spatula.” For the uninitiated, the Fandom site Encyclopedia SpongeBobia provides a background synopsis.

Visiting the Fry Cook Museum, SpongeBob and trusty starfish sidekick Patrick discover an Excalibur of exhibits: "Many have tried to pull this spatula out of this ancient grease, but all have failed. Only a fry cook who's worthy of King Neptune himself can wield the golden spatula.” Naturally, SpongeBob accidentally extracts the spatula, and Neptune promptly appears, challenging our hapless hero to the ultimate burger competition. Victory spells divinity for SpongeBob; defeat, the surrender of his beloved fry cook vocation forever.

“King Neptune makes 1,000 Krabby Patties, in the time it takes SpongeBob to make just one, winning the challenge,” the synopsis retells. “However, when Neptune shares his patties with the audience, they express that they taste awful. Neptune is angered by this and asks why they would think that SpongeBob's would be any better. He tastes SpongeBob's Krabby Patty and finds it delicious. … SpongeBob is declared the winner, but when he finds out that his friends cannot come with him to Atlantis, he tearfully refuses to go to Atlantis, and instead arranges for King Neptune to be a trainee under SpongeBob at the Krusty Krab, teaching him that ‘perfect Patties are made with love, not magic.’”

And as Arthur C. Clarke posited as his Third Law in "Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible," “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Or, as Joseph Heller famously wrote in "Catch-22," “the spirit gone, man is garbage.” All the tech in the world can’t substitute for love — not in the making of burgers, not in the feeding of others, and not in the living of life.

But wait, there’s more. The fan site synopsis leaves out the most important part — the drama of SpongeBob’s confrontation with the prospect of his transformation into a god.

For that, we can helpfully resort to the episode transcript.

SpongeBob: So, uhh, what do you think?

King Neptune: Yours is superior. Therefore, [bows to SpongeBob] ... I concede to you, SpongeBob SquarePants, you win.

[The crowd cheers]

SpongeBob and Patrick: Yeah! [both dancing] We're going to Atlantis! We're going to Atlantis!

King Neptune: [laughs]

SpongeBob: What's so funny?

King Neptune: You, SpongeBob. That repulsive thing in my palace?

SpongeBob: You mean, Patrick can't come?

King Neptune: [laughs] No, of course not.

SpongeBob: And my friends?

King Neptune: Ah, the only friend you need, my dear boy, is the royal grill.

Patrick: [crying and wiping his tears with a tissue] It was nice knowing you, buddy!

[…]

King Neptune: [luggage appears next to SpongeBob] Come, SpongeBob, grab your things! It's time to depart ... [a two-seater bike appears] ... to Atlantis! [rings bell and pats SpongeBob's seat]

SpongeBob: I ... I ... [cries] I don't wanna go!

King Neptune: It's too late now. I can't live without your burgers! [grows giant] You're going to be a god and like it!

[King Neptune zaps SpongeBob and he becomes a muscular god. But being the same size, he looks a little strange]

King Neptune: Maybe we do have a problem.

SpongeBob: [in a booming voice] Wait, Neptune! I have another idea!

Ah, there it is. It’s too late … I can’t live without your burgers. … You’re going to be a god and like it!

Little else captures with such economy the technological devil’s — I mean, uh, “Neptune’s” — bargain of a compulsory divinization. There’s no time left to escape. In 2009, posting on the website of the agent who plugged Jeffrey Epstein into the tech community, legendary futurist Stewart Brand reflected that “40 years ago, I could say in the 'Whole Earth Catalog,' ‘we are as gods, we might as well get good at it.’ Photographs of Earth from space had that god-like perspective. What I'm saying now is we are as gods and have to get good at it.”

Now, 15 years later, the propaganda pressuring us to believe it’s too late not to become posthuman divinities is harder than ever to escape or even ignore. But as SpongeBob reminds us, instead of becoming gods, we’ll, let’s say, look a little strange — that is, we’ll be freakish mutants unfit for either world, mortal or godly, enough to make any partial observer conclude we do have a problem. The task falls to us mere mortals to have another idea … one far more humble than the posthuman temptation allows: Carry on with our human lives, but in ways that ensure the heavenly Spirit may, and does, move within and among us. Lose that, and we lose everything — except responsibility for the monstrosities we will become.

Thanks, SpongeBob!