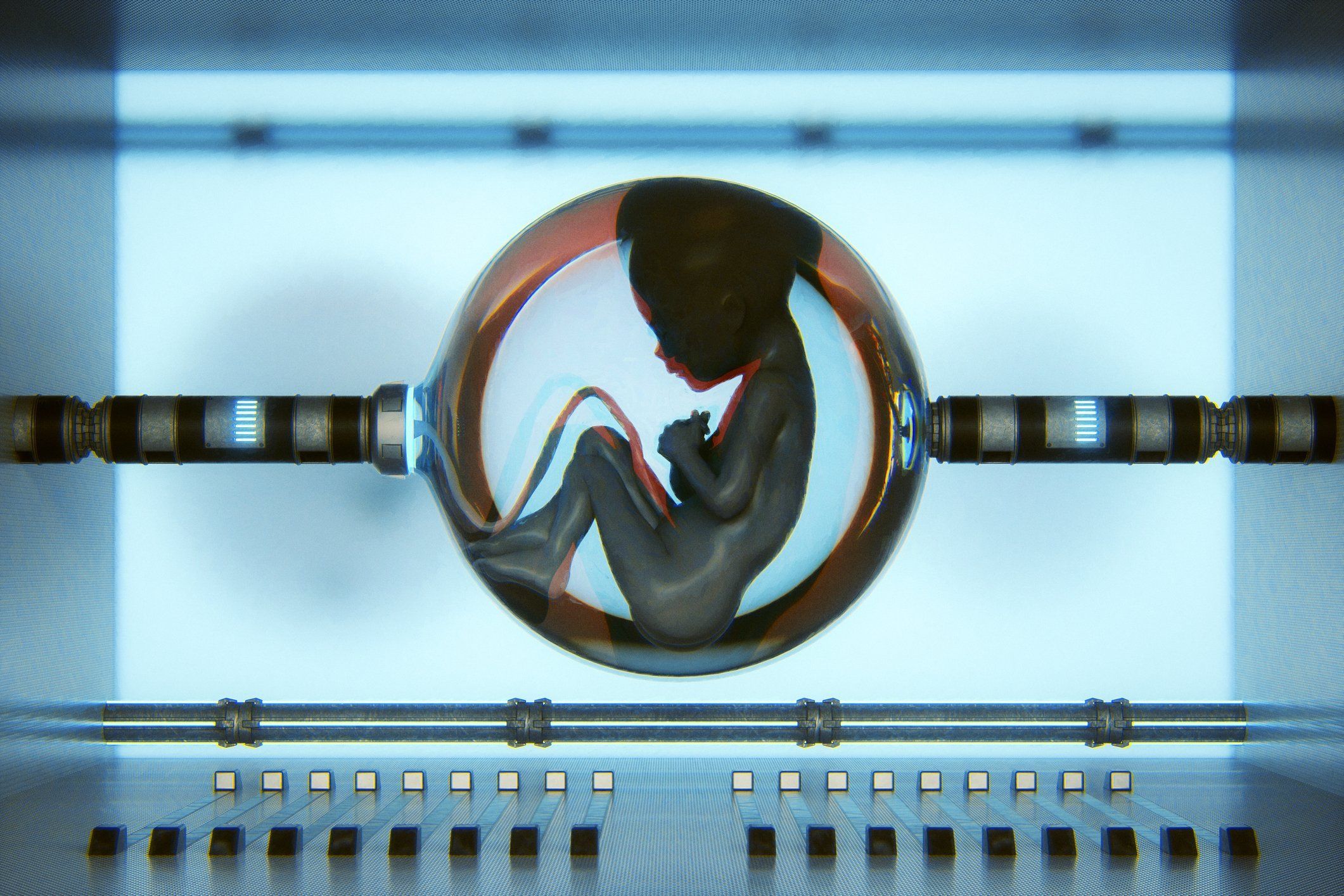

Can science birth artificial wombs? Lab-grown babies raise major ethical concerns

Since the first man, the human race has expanded and developed in a simple way: A man and a woman have sex, and a man's sperm fertilizes the woman's egg. Within four days of fertilization, a tiny cluster of cells begins to develop – the embryo. That embryo, which has now expanded to around 100 cells filled with fluid, travels along the fallopian tube and, within a week of conception, resides in the uterus, anchoring into the mother's body, growing by drawing nutrition from blood vessels and glands.

Within two months of conception, the embryo becomes a fetus and, after nine months, a baby. This is a miracle of human nature you likely learned in science class – and is solely down to the wonder of a mother's womb.

Infertility rates are rising by 1% every year in men. "By 2045, if that trend continues, the majority of couples would need reproductive assistance," Cohen says.

However, a minority of the scientific community have taken a different view. These scientists have a plan to remove the human from the post-conception process – to grow embryos independent of a womb and instead to nurture them artificially. The ability to independently develop a human being outside a mother's womb would have enormous ramifications for society and the human race. "What does it mean for society when we can produce children without any burden on women?" asks Maneesh Juneja, a digital health futurist. "It would have huge economic and societal effects."

Its potential has been backed by the likes of Tesla CEO and SpaceX founder Elon Musk and Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin, who have both said that the development of artificial wombs could solve the world's imminent population crisis.

The potential ramifications of this research are so significant that there are plenty of competing projects to try to bring artificial wombs out of the laboratory and into reality. Exo-Genesis, a community looking to promote the development of extra-uterine devices that can grow human babies in vitro, held its first in-person meetup in San Francisco in late February. Among the attendees was Divya Cohen, a medical doctor, MBA, and MPA with nearly two decades of experience in health tech startups. "I feel very strongly that we need to make this a reality," says Cohen.

About 13% of women want to be mothers but don't want to go through pregnancy. Infertility rates are rising by 1% every year in men. "By 2045, if that trend continues, the majority of couples would need reproductive assistance," Cohen says. "This isn't the only technology that would be useful, but it's certainly a tool."

Technological wombs

It's a technology that is reportedly being developed in university laboratories around the globe. China's Suzhou Institute of Biomedical Engineering and Technology claimed to have developed an AI-based technology that can nanny human embryos in artificial wombs by monitoring levels of nutrition and carbon dioxide in artificial environments that help grow embryos to term – a key issue in previous experiments that have tried to develop embryos outside a natural womb. The goal of the AI is to mimic the inexplicable alterations and changes that a mother's body subconsciously undergoes to nurture an embryo throughout pregnancy – and that is easier said than done.

While AI gained plenty of attention and many news stories, the reality is more prosaic: The technology hasn't been tested in humans. Despite the splashy headlines, it isn't guaranteed to be all that effective.

One project at the forefront of artificial womb development – one of three papers discussed at the Exo-Genesis meeting in San Francisco – was based in the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel. Alejandro Aguilera Castrejon is the lead author of the project to gestate a mouse embryo.

"The goal is to inject human cells into embryos to create chimeric models," says Aguilera Castrejon. So-called chimeric models, where human cells are injected into the embryos of other species and then tracked to model as closely as possible what would happen to the human cells in the embryonic stage, are used because it's impossible to conduct laboratory tests on human embryos.

Prior experiments had allowed similar chimeric-modeled embryos for two days – but Aguilera Castrejon's carefully monitored conditions permitted the embryo to grow for six days after it was implanted into a mouse, five days after fertilization. He and his colleagues are now working on starting the same process to grow embryos from day zero of fertilization rather than day five. The hope is that similar methods can be applied to humans. But there are some issues. The mouse embryos Aguilera Castrejon works with die after day eleven of the fertilization process because they become too big, preventing the oxygen and nutrients that would help them grow further from entering the embryo. "They basically die," he says.

That problem with mouse embryos is likely to be compounded with humans. Another challenge Aguilera Castrejon and his colleagues faced was keeping the embryo free of infection and contamination – an issue exacerbated should a similar experiment take place with human embryos because they take longer to develop. A mouse pregnancy lasts twenty days; humans, nine months. "The longer you have the embryo in culture, there are more things that can go wrong," he says.

The 29-year-old researcher, who has been working on his project for five years, believes that artificial human wombs are a while off. "In mice, I would say maybe it'll be a reality in ten years," he says. In humans? "I don't think I'll live to see humans," he says.

Aguilera Castrejon believes it'll take "at least fifty years" for science to bring a human embryo to full term and that it's not just the technological and biological challenges of doing so that are preventing development. In Israel, even if Aguilera Castrejon and his colleagues at the Weizmann Institute had the technical knowledge to grow a human embryo for the first month of its formation, they couldn't. "Maybe at some point society will advance to allow us to be born outside the uterus," he says. "I think technically this will be possible, but the main limit is the ethical aspect."

Regulations are being removed

In May 2021, the stem cell research community's public voice, the International Society for Stem Cell Research, dropped a rule that had previously prevented human embryos from being cultured for more than fourteen days. Some concerns remain about mixing human stem cells and non-human embryos in chimeric models – most recently over a 2021 U.S.-China project that combined humans with macaque monkeys – but there is a growing acknowledgment that such experiments are necessary steps for the future of fertility.

While Aguilera Castrejon is pessimistic that babies grown outside their mothers' wombs will be born in his lifetime, he does see a shift in attitudes, even in his five years in the field. For Cohen, the conversation must move beyond the field into the wider world. When she brings up the topic with her friends in science, they too often don't know about the risk of a potential population crisis. "We want [the rate of population replacement] to be 2.1, but in the U.S. it's 1.6, and in Japan it's 1.3," she says. "That means that we are very quickly turning into an upside-down pyramid society. If that continues, we're going to be in serious trouble by then. I think we could see a future similar to 'The Handmaid's Tale.' I used to read that book and thought it would never happen – but now the science suggests it could happen."

As for Aguilera Castrejon's skepticism about whether it's possible in his lifetime, Cohen says that we need less talking and more action. "I'm worried we're seeing a trend where that's going to hit us in 2045, and there are two alternatives," she says. "One is we get into this scary dystopian future, or we start working on the science and building what would help us outmaneuver that."