What did the Magi see? Decoding the mystery of the star of Bethlehem

Four years ago, in December 2020, a great conjunction occurred in the evening sky.

From the perspective of earthbound observers, this planetary event appeared as a close rendezvous of Jupiter and Saturn, the “gas giants” that are visible to the naked eye. It had been almost four centuries since the two planets had aligned so closely and almost eight centuries since this occurred at night.

Only a comet following a very specific trajectory could have done all that the Christmas star is said to have done, Nicholl argues.

Due to its brightness, the conjunction was easily visible in the evening sky, and since it happened in the month of December (culminating on the 21st), it was popularly known as a “Christmas star.”

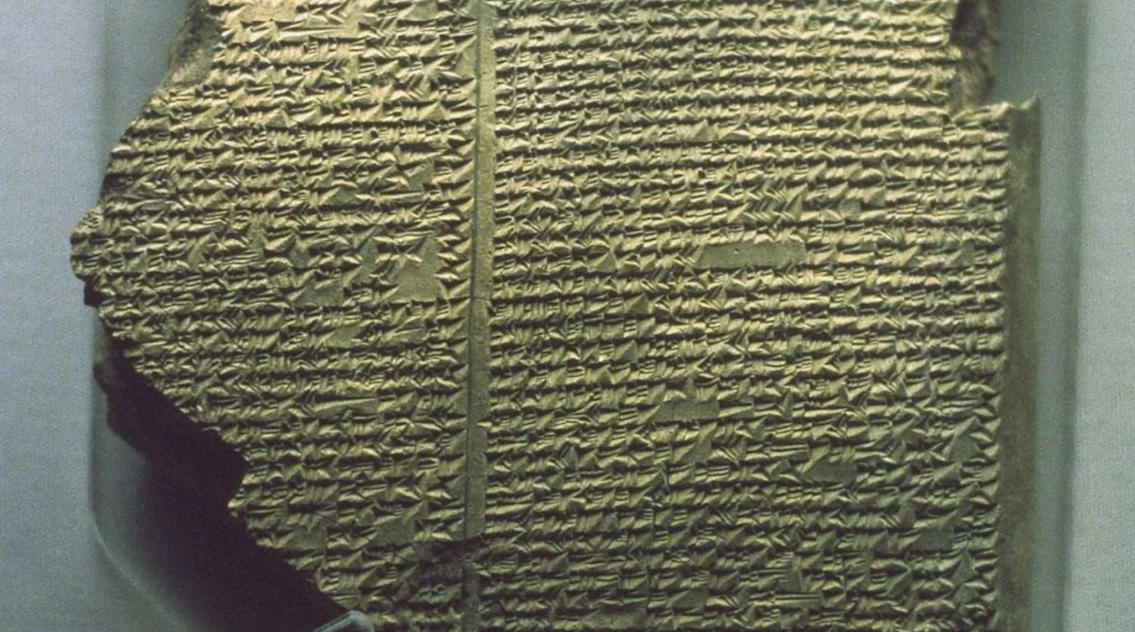

Over the centuries, many scholars have speculated about the nature of the actual Christmas star mentioned in Matthew’s Gospel — the one the Magi (who were astrologers) believed had royal significance.

As a child, I assumed that the star of Bethlehem was a miraculous de novo creation that served its purpose and then faded away. It wasn’t until adulthood that I learned of the various other proposals: a conjunction, a nova (a star that grows more brilliant for a time and then returns to its usual brightness), a meteor, or a comet. My great intellectual hero, Johannes Kepler, believed that the Magi saw a nova, perhaps within a constellation that indicated the birth of royalty.

Before considering two of the leading theories about the nature of the star, let’s take a look at the biblical account of the Magi. Matthew 2:1-12 (NET):

After Jesus was born in Bethlehem in Judea, in the time of King Herod, wise men from the East came to Jerusalem saying, “Where is the one who is born king of the Jews? For we saw his star when it rose and have come to worship him.” When King Herod heard this he was alarmed, and all Jerusalem with him. After assembling all the chief priests and experts in the law, he asked them where the Christ was to be born. “In Bethlehem of Judea,” they said, “for it is written this way by the prophet:

‘And you, Bethlehem, in the land of Judah,

are in no way least among the rulers of Judah,

for out of you will come a ruler who will shepherd my people Israel.’”

Then Herod privately summoned the wise men and determined from them when the star had appeared. He sent them to Bethlehem and said, “Go and look carefully for the child. When you find him, inform me so that I can go and worship him as well.” After listening to the king they left, and once again the star they saw when it rose led them until it stopped above the place where the child was. When they saw the star they shouted joyfully. As they came into the house and saw the child with Mary his mother, they bowed down and worshiped him. They opened their treasure boxes and gave him gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. After being warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they went back by another route to their own country.

What was this celestial object that rose from the east and then appeared to stop above the place where the holy family dwelt?

In the context of the passage, it seems that Herod was previously unaware of any novel astronomical event. Anything remarkable would have been observed by the majority of people living under those ancient glittery skies, when phenomena weren’t obscured by light pollution. Furthermore, Herod’s court astronomers would surely have noticed (and reported) anything particularly rare that went unnoticed by casual observers.

In "The Great Christ Comet: Revealing the True Star of Bethlehem," biblical scholar Colin Nicholl persuasively argues that the object in the night sky that led the Magi on their journey was a comet.

With impressive precision, Nicholl explains how a comet could have guided the Magi to Jerusalem, then Bethlehem, and finally to the house where Mary, Joseph, and the infant Jesus were staying. When the star appeared to stop over the place where the Christ child could be found, this was the comet “descending” toward the far horizon. Only a comet following a very specific trajectory could have done all that the Christmas star is said to have done, Nicholl argues.

I read Nicholl’s book when it was first published, and because I did not have the requisite training in astronomy to judge the veracity of the more technical aspects, I was thrilled to discover a book review written by Dr. Guillermo Gonzalez, the astronomer who co-authored "The Privileged Planet."

He writes:

The input from astronomers is evident in the high quality and great depth of discussions relating to the technical aspects of astronomy. Nicholl carefully explains the basic motions of celestial bodies in the night sky, always with attention to details relevant to ANE [Ancient Near-Eastern] observers. He also does a very good job explaining the anatomy, orbital mechanics, brightness changes, and visual appearances of comets. … I couldn’t find any obvious errors in the book’s astronomy content.

Gonzalez concludes his review by saying that he’s tempted (despite minor issues, such as a chronological discrepancy concerning Herod’s reign) to say that Nicholl has solved the mystery of the Bethlehem star.

Gonzalez points out that “even a single brief note of a comet appearing at a certain date and in a particular constellation consistent with Nicholl’s theory would be enough to confirm it.”

Another theory that I think has great merit is presented in "The Star of Bethlehem: The Legacy of the Magi" by Michael R. Molnar.

For part of his career, Molnar served as an astronomy professor at Rutgers. He was also a collector of ancient coins and enjoyed writing articles about the intriguing astrological symbolism found on some. He believed that one of his acquisitions, a Bronze Age Roman coin featuring a leaping ram gazing back at a star, was directly relevant to the biblical account.

The image symbolizes Jupiter moving through the constellation of Aries (the Ram), a phenomenon that is known to have occurred in 6 B.C. The bright planet passed through the constellation and then went into retrograde (backward) motion, which sent it through Aries a second time, where it then appeared to briefly stop prior to resuming its forward orbital motion. Twice, a lunar occultation took place (the moon eclipsed Jupiter), for the first time on March 20 and the second time on April 17. According to ancient astrology, a lunar occultation of Jupiter was indicative of a king’s birth.

Moreover, Claudius Ptolemy, the famous pagan astronomer who devised the long-reigning geocentric cosmology based upon Aristotelian principles, wrote in his "Tetrabiblios" that the land of Judea was ruled by the constellation Aries. Other astrological sources corroborate Ptolemy in this assertion. Thus, says Molnar, the astrologers would have viewed this event as indicative of the birth of a great king in Judea.

Nicholl offers a point-by-point critique of Molnar’s theory in his book. First and foremost, he says, is the problem that neither of the lunar occultations of 6 B.C. would have been visible in Babylon, from whence the Magi would have traveled.

In addition, a lunar occultation of Jupiter in Aries wasn’t incredibly rare; another instance followed in 54 A.D. Nicholl lists several other reasons why he thinks Molnar’s theory is deficient, some of them more convincing than others. Still, the fact remains that there’s currently no known record in the ancient literature of a comet passing over the ancient Near East within a viable time frame.

Ultimately, we may never have a definitive solution to the mystery of the Bethlehem star, but the speculations are quite fascinating! Perhaps more clues will surface as research continues.

This article is adapted from a post that originally appeared on the Worldview Bulletin Substack.

One day, they stopped selling their cinnamon scones. Then I started noticing an uptick in crystals, tarot cards, and astronomy books.

One day, they stopped selling their cinnamon scones. Then I started noticing an uptick in crystals, tarot cards, and astronomy books.