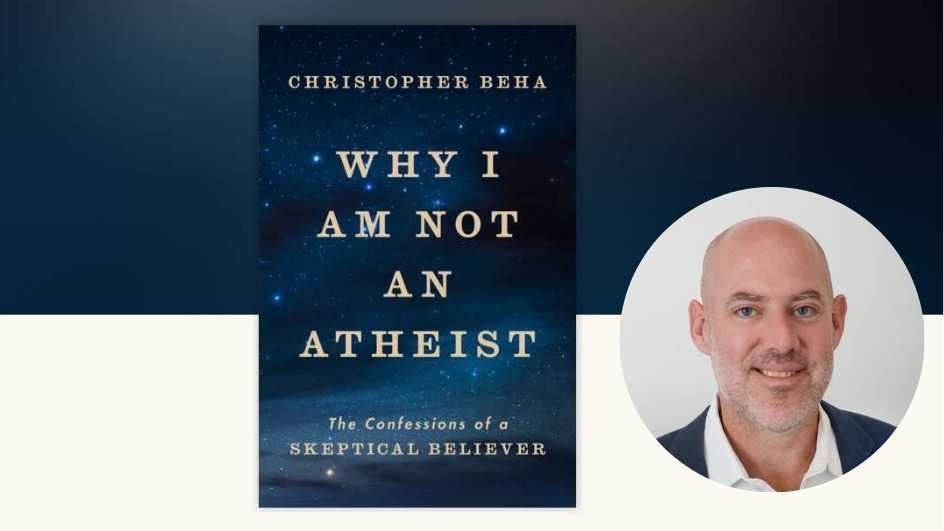

'Why I Am Not an Atheist' exposes incoherence of non-belief

Atheism likes to present itself as the adult in the room. Faith, by contrast, is cast as a childish indulgence for people afraid of the dark.

Christopher Beha’s "Why I Am Not an Atheist" examines this framing and demonstrates, with real precision, why atheism itself may be the most adolescent worldview of them all.

Atheism has a curious habit. It borrows Christian language — dignity, justice, compassion — while denying the metaphysical foundation that gives those words meaning.

This isn’t a book of defensive apologetics. Beha doesn’t hurl Scripture at doubters or claim that God can be demonstrated like a physics equation. Instead, he treats atheism as a coherent position and then tests it against reality. He walks its reasoning to its natural conclusion and reports back on the damage. What he finds there isn’t liberation but emptiness — sometimes dressed up as sophistication, sometimes as certainty, but emptiness all the same.

Godless

Beha’s journey begins in familiar territory. Like many sane, decent people, he wanted honesty. He wanted to “look the world frankly in the face,” to set aside inherited beliefs that, at that stage of his life, he believed couldn’t withstand scrutiny. God, to him, seemed unnecessary. Worse, He seemed embarrassing. Atheism, on the other hand, felt like intellectual courage.

Beha embraced the godless creed at first, wholeheartedly. But it didn’t take long for cracks to appear.

Rather than joining the professional atheist class — the permanently outraged and faintly condescending set, à la Harris and Dawkins, who mistake self-indulgence for insight — Beha asks a far riskier question: What replaces God once He’s gone? Not as a thought exercise, but in real life. In daily choices. In suffering. In death.

Here, the book begins to shine.

Motion and chaos

Beha identifies two dominant atheist positions. The first is scientific materialism, which holds that only what can be measured is real. Everything else — mind, love, conscience, beauty — is reduced to physical process. Choice becomes brain chemistry. Human life is explained as motion and chance, sorted into probabilities.

The second is a newer, trendier alternative: romantic idealism. Instead of reducing the world to atoms, it centers everything on the self. Meaning is something you create. Truth is something you feel. The highest good is authenticity, and the highest crime is judgment. God disappears, and the individual assumes His place.

Both, Beha argues, fail in opposite but equally revealing ways.

Materialism reduces the human person to a biological incident. Consciousness becomes a chemical glitch. Love becomes an evolutionary strategy. It is an impressively sterile system, one that explains everything except why anyone should bother getting out of bed.

Romantic idealism reacts against this coldness by putting the individual will on the throne. The view seems warmer, and perhaps it is, but it is still incoherent. If everyone creates meaning, meaning ceases to exist. If truth is personal, truth dissolves. The self becomes both king and casualty, crowned with responsibility and locked in solitude.

Between them, Beha shows, modern atheism swings between delusion and despair. That may explain why so many of its most visible champions — from Bill Maher to Ricky Gervais to Penn Jillette — sound less liberated than irritated. Atheism can take things apart, but it can’t hold them together.

RELATED: Did science just accidentally stumble upon what Christians already knew?

Philosophical freeloading

What makes this critique effective is Beha’s refusal to hide behind abstractions. He doesn’t pretend that these systems fail only in theory. They fail in lived experience. They fail when existential angst arrives uninvited.

Atheism, Beha observes, has a curious habit. It borrows Christian language — dignity, justice, compassion — while denying the metaphysical foundation that gives those words meaning. It wants human rights without a human giver. What looks like intellectual bravery is closer to philosophical freeloading.

Beha is especially critical of the arrogance that often accompanies unbelief. Atheism flatters itself as fearless while demanding a strangely narrow universe — one small enough to fit inside a laboratory or a podcast episode. Anything that resists measurement is dismissed as childish. Transcendence is treated as something reserved for uncultured troglodytes.

Christianity, by contrast, has never sold comfort by making reality smaller. It doesn’t reduce the world to what feels manageable. It claims that meaning is real whether we want it or not, that God isn’t a projection of human wishes, and that right and wrong aren’t personal inventions. It doesn’t erase suffering. Instead, it meets it head-on. To be alive is to bear pain, and to bear pain is to be alive.

The way back

It is from within that hard-earned contrast — after years in the wilderness of unbelief — that Beha finds his way back, not to a vague faith, but to Christianity itself and finally to the Catholic Church. This isn’t a story of conquest. It’s an acknowledgment that atheism, however confident it sounds, left him more miserable and taught him to call that misery freedom — something he came to see clearly when his brother Jim nearly died in a car crash and later when he himself faced death with stage-three lymphoma.

Crucially, Beha isn’t arguing that faith banishes doubt. He would laugh at that idea. He remains a skeptic in the classical sense — aware of human limits, suspicious of tidy conclusions, allergic to ideological shortcuts. Faith, as he presents it, is the decision to live as though truth, goodness, and meaning are not clever hallucinations generated by neurons killing time.

For conservative Christians, "Why I Am Not an Atheist" matters because it doesn’t preach. It doesn’t wring its hands over secularism or bulldoze unbelievers. It does something far more damaging: It lets atheism talk, at length. Given enough space, its confidence begins to crack, its claims lose shape, and its bravado gives way to a worldview that can’t deliver what it promises. Atheism isn’t undone here by counterargument, but by relentless exposure.

In an age when disbelief markets itself as adulthood and faith as regression, Beha offers a bracing reversal. Atheism, he suggests, is a creed without the slightest bit of substance, built entirely on what it denies.

Christianity, whatever one’s denomination, remains the only worldview bold enough to say that life matters, suffering is not pointless, and belief answers to what is, not what we want.

A two-hour discussion between Sam Harris and Ross Douthat revealed just how much the world has changed since the rise of the New Atheists.

A two-hour discussion between Sam Harris and Ross Douthat revealed just how much the world has changed since the rise of the New Atheists.

AlessandroPhoto/iStock/Getty Images Plus

AlessandroPhoto/iStock/Getty Images Plus  Viktor Aheiev/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Viktor Aheiev/iStock/Getty Images Plus

vchal/iStock/Getty Images Plus

vchal/iStock/Getty Images Plus

francescoch/iStock/Getty Images Plus

francescoch/iStock/Getty Images Plus

ra2studio/iStock/Getty Images Plus

ra2studio/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Photo by OLI SCARFF/AFP via Getty Images

Photo by OLI SCARFF/AFP via Getty Images