Why Christians Should Build Cathedrals

There is nothing vainglorious about giving glory to God with the best works of our minds and our hands.

There is nothing vainglorious about giving glory to God with the best works of our minds and our hands.We are born with an intrinsic ability to recognize beauty, be it a sunset, a piece of art, or a fellow human being. The second our eyes behold something beautiful, we can’t help but stop and admire. No one teaches us to react this way; it just happens naturally.

Michelle Obama, however, argues otherwise. On a November 12 podcast episode titled “The Power of Hair: Identity, Legacy & Black Womanhood,” the former first lady posited that the world needs to be taught how to appreciate black beauty in particular.

The episode, which featured Cosmopolitan beauty editor Julee Wilson, actor and producer Marsai Martin, and stylist and founder of Esthetics Salon Yene Damtew, was part of the promotional content for Michelle’s new book, “The Look" — a glossy vanity project that repackages the same grievance-laden identity politics she’s been peddling for years under the guise of empowerment and joy.

After declaring that “there isn't a standard of beauty” and that what we see featured in magazines is merely “taste” and not beauty, she stressed the need “to start educating people about all kinds of beauty.”

“Our beauty is so powerful and so unique that it is worthy of the conversation and it's worthy of demanding the respect that we're owed for who we are and what we offer to the world,” she added.

“I didn't need an education on [beauty]. I can remember at a very early, early age the ability [to recognize], ‘Oh, that's a beautiful woman; that’s a handsome man,”’ counters Jason Whitlock, BlazeTV host of “Fearless.”

“Fearless” contributor Shemeka Michelle agrees. “You don't have to teach about beauty — it just is. Michelle sounds so silly, and every time we turn around, here she comes, just another round in the victim Olympics.”

Contrary to Michelle’s belief, objective beauty is real, but “attitude,” Jason argues, can certainly go a long way in the beauty department. Kindness, confidence, faith in Christ — these are all beautifiers, he says.

Unfortunately, many women, he says, adopt the kind of attitude that detracts from the natural beauty they possess. “That’s this feminism that many black women and girlbosses have attached themselves to,” he says. “It erases a lot of their beauty. That bitterness and anger just is not attractive.”

“When you're sitting around and you're a multimillionaire and the world has kissed your butt and … then you're still angry and whining and complaining and demonizing America, it's just very unattractive,” he says.

Jason and Shemeka both agree that Melania Trump, with her timeless poise and quiet grace, is a far better example of beauty than Michelle Obama will ever be.

To hear more of the conversation, watch the clip above.

To enjoy more fearless conversations at the crossroads of culture, faith, sports, and comedy with Jason Whitlock, subscribe to BlazeTV — the largest multi-platform network of voices who love America, defend the Constitution, and live the American dream.

Chances are that you've disagreed at least once with a family member, friend, or co-worker about what counts as "true" or "real" art.

This usually plays out as a right vs. left divide. People on the right are often suspicious of art that pushes too far beyond familiar social boundaries. The left, on the other hand, embraces innovation and art that breaks with what's traditionally accepted. In reality, these attitudes share the same nontraditional view of art. The tension has been unfolding for the last 500 years. It's the story of modern art, born from a fundamentally disordered relationship to art itself.

A modern art museum looks less like a celebration of art and more like a graveyard.

Imagine you and a friend are on a trip, and you decide to visit the Guggenheim art museum. There, you both see "Comedian," a piece by artist Maurizio Cattelan that sold for $6 million at auction. Before you is a banana duct-taped to a wall — that's it.

Unable to suspend disbelief, you say, "How is that art?"

Your friend replies, "Art is subjective. Who are you to say this isn't art?"

Simply all you can say is, "I cannot see beauty or skill in this."

So your friend rejoins you in a vacuous, "Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. But you wouldn’t understand. Anyway, this is a commentary. It’s about the concept of the artwork."

Critics beat the "Comedian" to death not because of its unique absurdity but because of its recency. The Dadaist art movement has pulled stunts like this one for more than 100 years. It reminds me of the infamous "Fountain" by Marcel Duchamp: a urinal with a signature. It was exhibited 108 years ago.

But how did we get here?

To understand how we arrived at this predicament in Western art, we must examine our relationship to it, how we receive art, how we engage with it, and its history.

The modern period marks a departure from the pre-modern world (i.e., year 1500 A.D.). It's a turning point in history unlike any before. Everything changed, including the ways in which people perceive reality. Gone are the days of enchantment. Now we have rationality. A Faustian bargain was made.

"What is art?"

When someone asks that question, what immediately comes to mind? Most people think of painting, drawing, sculptures — things that belong in a museum. But this modern way of thinking about art is novel, foreign to people in the pre-modern world. Calling that era "pre-modern" is misleading because it makes up the vast majority of human history. The real anomaly is the modern period.

Seen from this perspective, a modern art museum looks less like a celebration of art and more like a graveyard.

For the ancient and medieval person, art was integrated into life itself — not separated from it. Art was less a noun than a verb, something one did. People didn't create art; they "art-ed" or were "art-ing." Art was a process of participation. Put simply: There was no distinction between "art" and "craft" as we think of it today.

Modern people haven't abandoned this concept entirely, but it no longer sits at the forefront of how we think about art. It survives in words like "artisan," referring to bakers, tailors, and other craftsmen. It lingers in expressions like "the art of watchmaking" or "the art of conversation." Even commercial marketing borrows it. Products marketed as "artisan" purport to distinguish craftsmanship from mass-produced commodities.

In the pre-modern world, everyday life was shaped by art. Daily clothes, a dining room table, the family home, the local church — from the lowliest object to the most sacred — all were made with care and beauty. On one level, this is easy to explain: Everything was handmade, and because possessions were less numerous, people valued and cared for them, passing them down through generations.

RELATED: How modern art became a freak show — and why only God can fix it

Naturally, if you own something that long, you want it to be beautiful.

But more fundamentally, all of these objects fit into the same pattern that we call "art": the gathering and ordering of particular items in a way that speaks to human perception. A finely crafted dining table binds a family together more than a folding card table ever could. The liturgical cup used for the Eucharist is fashioned from precious metals and decorated with deliberate symbols, while the wine glasses at the family table, though well made, are more austere.

Each object bears an artfulness appropriate to its purpose, something obvious to the pre-modern mind.

This older way of living with art is not completely lost on us today. It still exists, though less prominently and increasingly in decline. Yet one demotion of art is almost extinct in the modern world, surviving only in tight-knit communities, ethnic traditions, and older generations. It may not immediately register as "art" at first glance, but folk dances, dinner parties, storytelling, and other forms of social ritual are actually higher forms of art than material objects. They are art as shared life.

Material art matters, too, but it mainly points us toward the deeper loss.

One simple historical fact makes the difference clear: Pre-modern artists didn't sign their work.

The transition to modernity was, as in so many areas of life, a pact with the devil. Technical mastery was gained, but the spiritual core was left void. The Enlightenment promised reason, science, and progress, so it seemed that humanity could finally cast off the shadow of the past and secure its future. But the human condition didn't change.

What convenience gave with one hand, it robbed from the soul with the other.

Industrialization, mass production, plastics, and now the digital age each dealt successive blows to our once-integrated relationship with art. In the pre-modern world, art was an integrated part of life. Modernity replaced this with self-consciousness. Art became not a relationship but a category. Crafts were dissected under the microscope of science, refined to new levels of technical brilliance. The results were often dazzling: new techniques, perspectives, and ways of depicting the world.

But the cost was steep.

As long as people exist, art will exist. But the toothpaste is out of the tube. There is no going back.

This story unfolds in art history. By the late medieval era, traditional iconography, steeped in centuries of sacred meaning, was being reshaped by artists like Duccio and Giotto. The Renaissance largely abandoned these forms, with titans like Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci leading the way. By the 1570s, El Greco was embedding sexually transgressive and even blasphemous subtleties into his work.

This trajectory continued, sometimes slowly and other times all at once. But the pattern was clear: identity fragmented, transcendence severed, innovation pursued for its own sake. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the seeds had fully flowered. Soviet brutalism imposed tyranny through pattern and abstraction, while Dadaism dissolved meaning altogether until art and non-art were indistinguishable.

The result? Today, we argue with friends about whether a banana duct-taped to a wall is "art." Art has become commentary on commentary, detached from human experience, and reduced to little more than propaganda.

Today, modern art is defined by its fixation on individual idiosyncrasies. At its extreme, it becomes nothing more than the subjective whims of the isolated self disconnected from reality.

Does this mean that culture and beauty itself have reached their end? Thankfully not.

As long as people exist, art will exist. But the toothpaste is out of the tube. There is no going back. We cannot rewind the clock to some imagined golden age. That sentiment is not only impractical, but it's impossible.

We are where we find ourselves today because of the past, so such a return would lead us back to today. The path forward, then, must connect the present to the past, the new and the old, weaving together the modern and the pre-modern.

One bridge across the divide is found in the work of Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky, who is widely regarded as one of the greatest directors and screenwriters of all time.

Unbeknownst to him, his life was a crossroads: Raised in the Soviet Union under militant atheism and the revolutionary spirit of modernism, yet he was an Orthodox Christian, steeped in the traditions of the pre-modern world. His father was a poet, and his mother was a lover of literature. Tarkovsky was perfectly positioned to bring the old and new into dialogue.

His art is a call to repentance, an offering and pleasing aroma to the Lord.

Tarkovsky saw modernity clearly: "Man has, since the Enlightenment, dealt with things he should have ignored."

The heart of Tarkovsky's vision was simple: art as prayer. He admitted that Dostoevsky — another Russian and Orthodox Christian who wrestled with the sacred and the existential — was the greatest artist. Tarkovsky wore this influence on his sleeve. His films probe life, death, suffering, and the search for the miraculous and meaning. He once wrote, “The aim of art is to prepare a person for death, to plough and harrow his soul, rendering it capable of turning to good.”

In his films, Tarkovsky magnifies the specific experiences of the individual, yet he always frames them in transcendence. He gathers the unique and lifts it upward. But he does not erase human subjectivity. Rather, he redeems it.

As he put it:

When I speak of the aspiration towards the beautiful, of the ideal as the ultimate aim of art, which grows from a yearning for that ideal, I am not for a moment suggesting that art should shun the "dirt" of the world. On the contrary! The artistic image is always a metonym, where one thing is substituted for another, the smaller for the greater. To tell of what is living, the artist uses something dead; to speak of the infinite, he shows the finite. Substitution ... the infinite cannot be made into matter, but it is possible to create an illusion of the infinite: the image.

In this way, Tarkovsky reverses modernity's desecrations and successfully connects the modern and pre-modern. He uses the individual to orient us toward God, a spiritual transcendence of sorts. Where the modern world has made the holy profane, Tarkovsky, in a Christ-like reversal, makes the profane holy.

His art is a call to repentance, an offering and pleasing aroma to the Lord.

"The artist is always a servant and is perpetually trying to pay for the gift that has been given to him as if by miracle. Modern man, however, does not want to make any sacrifice, even though true affirmation of self can only be expressed in sacrifice," he once said.

What does this mean for us? It means embodying art in our daily lives.

You don't need to be a professional artist. Do things deliberately and with care. A mother preparing a meal gathers the fruit of local soil into the higher good of uniting her family. A father telling a bedtime story practices one of the most ancient and enduring arts.

But the key is purpose. When art is done for its own sake — or worse, for the sake of self — it collapses and is degraded. A meal made not to bind the family but only to satisfy hunger soon degenerates into the TV dinner. A story rushed through without care decays into mass-produced entertainment stripped of substance.

If this is true of everyday arts, how much more of the fine arts? A painter who works only from private interiority — detached from a holy purpose — quickly drifts into solipsism, creating images disconnected from reality. An iconographer, by contrast, paints for veneration, anchoring a community's worship in something beyond themselves. One isolates; the other binds together. One closes in on the self; the other points beyond it.

Art created for no other purpose than for the self is disconnected from all and devoid of any real power or meaning.

There are signs of hope. Traditional religious communities, specifically liturgical Christian traditions (like the Orthodox Church), maintain and produce work of depth and beauty: the ritualistic, iconography, music, homiletics, and so on — all built around a sincere Christian framework. The Orthodox Arts Journal showcases this revival. And in addition to liturgical arts, it has begun integrating beauty into popular art forms like graphic novels, fairy tales, literature, and clothing.

Revival, however, can't remain institutional. The hard work of beauty must be done in your own home and life.

Modern technology allows anyone to become an artist in any field. But the burden of self-awareness requires you to carve out time and put in real effort. And it's not enough to create beauty yourself. You must also reject the cheap slop offered to you and choose real craftsmanship.

The road is narrow and hard. But if you want to be delivered from the hell of modern art, go make a pleasing sacrifice to the Lord.

American business has lost the last shred of the plot.

Cracker Barrel’s bone-headed “rebranding” — more on this below — is only the ne plus ultra of a long, stupid march through formerly beloved brands toward a joyless, millennial-gray final destination.

These are choices we’re making. Bad choices. Anti-beauty choices. Anti-human choices.

Look around you. What do you see? Alleged restaurants that look like industrial warehouses. Businesses that we used to call bakeries — everything is just a “store” now in modern corporate-speak — now decorate their interiors according to surgical sterile-field protocols.

Everything is hard, not soft. Everything is gray, not green. Everything is fluorescent, not incandescent. Everything is aluminum, not velvet.

You know what I mean because you see it everywhere. The built world has been drained of color, curve, ornamentation, and whimsy. The desiccated architectural corpses of abandoned Pizza Huts with their distinctive step-peaked roofs litter the suburbs. I found these sad to look at until I realized that Pizza Hut is in a better place now, where there’s no more pain.

It’s McDonald’s we need to worry about. Cast your mind back to your childhood when you first met Ronald, Grimace, and Mayor McCheese. Most McDonald's restaurants had a playground for kids with colorful characters. The buildings themselves promised fun and piqued your imagination. Like Pizza Hut, McDonald's roofs had angles and character. They were painted bright red with French-fry-yellow accents.

Observe a McDonald's today. The buildings are the best representation of the Brutalist revival taking over modern architecture.

At best, they’re abstract, cubist boxes that offer the eye no rest. Hard edge overlaps hard edge. All ornamentation is stripped. Color is canceled. You get gray and brushed aluminum, and you better damned well like it.

The worst part is how the company has kept one bit of color — the famed golden arches. Stuck on these industrial boxes as an afterthought, you’d be forgiven for thinking McDonald's is making a joke at our expense: “Look what we took away from you. Lol. Lmao.”

These buildings aren’t restaurants; they’re wholesale crematories at the back of an industrial park.

Automobiles are the same.

No, dear reader. Let me stop you before you start typing that comment. All cars don’t look exactly the same “because aerodynamics, and this is the optimal shape, and they have to do it to meet emissions standards.” That’s the “well, it’s not really as bad as you say” excuse.

It’s just not true (and it is as bad as I say). If it were true, then every single car would be exactly the same as every single other car. But they’re not. There are SUVs, for example. If “they have to do it for aerodynamics” were true, this size and shape of vehicle would not exist. Oversized, elevated rectangular boxes, by their nature, are un-aerodynamic. A Chrysler Airflow from 1934 has a much higher aerodynamic rating than any modern “luxury truck” and still manages to be pleasing to the eye.

It’s not “because they have to because government.” It’s because there’s something wrong with us. We’re sick at heart and sick in the soul, and our emptiness finds three-dimensional expression in the sea of white, black, gray, and silver cars that all look precisely the same as every other maker’s car in that vehicle class.

These are choices we’re making. Bad choices. Anti-beauty choices. Anti-human choices.

You’ve likely heard of the recent kerfuffle over the “rebranding” of the Cracker Barrel restaurant chain. Cracker Barrel is a chain of down-home restaurants that serve unfussy American food like your grandmother used to make. Created in 1969, the founders wanted to offer a restaurant that would remind people of the comfortable general stores and wayside diners that once dotted the American rural landscape. Nothing fancy, just plain food cooked well and served in an atmosphere that invited you to sit down, take a load off, and have supper with other good people.

Staff would travel to flea markets and estate sales to pick up real Americana to stick up on the walls. There were framed pictures of famous boxers and lacrosse sticks, big kerosene lamps that used to light and heat the general stores. The effect was a combination of grandma’s attic and grandpa’s work shed, with a little bit of Christmas thrown in.

Take a look at how Cracker Barrel used to look.

Now, take a look at the “refreshed” Cracker Barrel.

From your grandparents’ house to the prison commissary.

RELATED: Bud Light insider reveals what led to Dylan Mulvaney controversy

Who makes these decisions? What kind of person takes a beloved restaurant brand and sticks up her middle finger to the customers? A middle-aged, corporate, almost certainly liberal-woke-Karen type. And here she is, Cracker Barrel CEO Julie Felss Masino, cackling on breakfast television behind oversized look-at-me glasses, telling the audience how much everyone just SUPER LOVES what we’ve done, and we’re doing it all out of LOVE 4 U!!!!!

American business apparently learned nothing from the Bud Light fiasco. In that case, a younger Karen named Alissa Heinerscheid sent the company’s profits into the toilet by making fun of her own brand’s “frat boy” image and slapping the face of a demented drag queen on the cans.

America, we have to come back to our senses. The world doesn’t have to conform to Karen’s diktats. Karen hates us and hates the things we like, which is why she punishes us. But we’re not her children (do say a prayer for them), and we don’t have to listen to her.

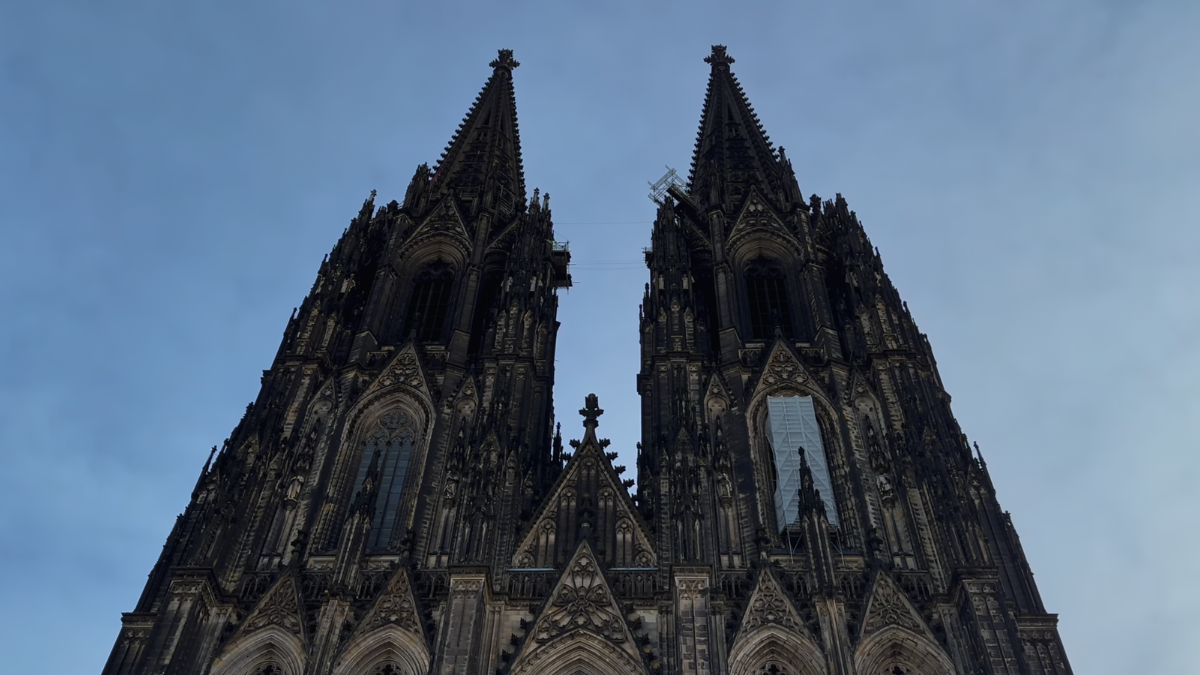

God gave us a world of curve, color, romance, and beauty. For thousands of years, men have tried to follow this example by piling up stones and locking logs together in pleasing shapes that ennoble us and make our souls sing. The deracination of the beautiful and the divine started long ago with churches. We don’t build anything worthy of the name “cathedral” any longer; instead, we put up Brutalist boxes and stick a Mary-on-the-halfshell on the lawn.

The sickness that compromised matters spiritual is now devouring things temporal.

Beauty is our patrimony and our birthright. Let's take it back.

The recent outrage over an American Eagle ad featuring actress Sydney Sweeney would be hilarious if it weren’t so revealing. The ad shows Sweeney wearing jeans with the cheeky caption, “Sydney Sweeney has great jeans.” It’s a harmless pun — wordplay on both genetics and denim.

But as we know, grievance culture doesn’t do humor. According to outraged leftists, this ad is “Nazi-coded propaganda” because Sweeney has the wrong look: blonde hair and blue eyes. That’s right — Sweeney didn’t goose-step across your screen or quote “Mein Kampf.” She just smiled in a pair of jeans. Apparently, that was enough to unleash the fury of the perpetually offended.

It’s not a crime to recognize beauty. It’s an act of sanity.

Why does something so lighthearted spark such disproportionate rage?

At first glance, the reaction seems to fit a familiar pattern. Sweeney is white. She’s conventionally attractive. She’s not apologizing for either of those things. That’s three strikes in the diversity, equity, and inclusion playbook.

The new cultural catechism of the left says that beauty is a “social construct.” It’s used by oppressive systems to maintain unjust hierarchies, so it must be redistributed according to equity quotas.

Admiring beauty becomes an offense. It must be deconstructed — if not altogether abolished — and reprogrammed with DEI.

But there’s something deeper at work — something more visceral and more theological. You can sense it in the feral energy of the backlash. It’s not just that Sweeney is beautiful. It’s that she didn’t earn it. And the leftists are mired in high-schoolish insecurity.

She didn’t pass a DEI review. She didn’t seek approval from the sensitivity board. Her looks aren’t the result of a curated political identity — they’re the result of, well, her parents.

And that’s what drives the left insane. Beauty, in this case, violates the central tenet of their moral framework: fairness. Sweeney didn’t do anything to deserve being attractive (aside from perhaps watching her diet and going to the gym). Her features are, largely, inherited — in their language, “privilege.”

The old-school leftists like Herbert Marcuse rightly critiqued the one-dimensionality of ads like American Eagle’s. Commercial culture does not aim at beauty, truth, or goodness. But the modern leftists dropped that message. Now, beauty is whatever the activist class tells you it is, as long as it serves the cause.

This is the theology of the grievance industrial complex: If something is unearned, it’s unjust. It's just not fair. “Why not me?” is the battle cry — less a revolution, more a toddler’s tantrum.

This is why leftists don’t just go after people — they go after beauty itself. I’m not equating sex appeal to beauty. But the outrage is beyond sex appeal and is aimed at the very idea that someone can be beautiful without approval from the Committee of Twelve.

Spend five minutes on any state university campus or in Democrat-run city and look at the newest buildings. They are intentionally not beautiful. They have even abandoned Soviet functionality. Concrete cubes with exposed ductwork and LED-lit virtue slogans where cornices and stained glass used to be are statements of contempt, monuments to cynicism and self-hatred, rather than structures designed to lift the soul.

The leftist assault on beauty goes beyond architecture. University art galleries — such as the one run by my school, Arizona State University — are considered “activist installations.” Chaotic splashes of rage, deconstruction, profanity, and noise aren’t merely misguided attempts at beauty — they are refusals of it. They reject order and celebrate cacophony.

This reveals a deeper truth: Leftists' war on beauty is ultimately a war on God.

Beauty is not a construct. It is not the invention of Western power structures. Beauty is real — it flows from the nature of God Himself. As Augustine wrote, ”Being is good.” Evil is not a thing in itself. It’s the corruption of the good. Likewise, beauty is not a weapon of oppression. It’s the radiance of order, truth, and harmony.

But if you hate the Creator, you will hate creation. You won’t rejoice in beauty; you’ll resent it. The truly dark impulse behind much of leftist cultural production is not liberation. It’s vengeance.

A world that won’t conform to their demands must be punished. If they can’t make reality fair by their standards, then they’ll make it ugly and demand that you call it a masterpiece

But you aren’t required to play along. You don’t have to pretend that brokenness is beauty, that chaos is art, that bitterness is profound, or that atheism is intellectually deep.

You don’t have to nod along when they tell you that Sydney Sweeney’s ad is a hate crime and that art school murals of screaming female body parts are sublime. You can say, without apology: That’s not beautiful.

RELATED: Hot girls and denim: American Eagle rediscovers a winning formula

And that’s a kind of cultural resistance we desperately need. Christians in particular must recover a theology of beauty. We serve the God who clothes the lilies of the field in splendor, who filled the skies with stars and the oceans with wonder, who made the human form. This God of beauty is the same one who redeems the lost sinner and works all things together for good.

So don’t let the rage mob deprive you of beauty. Don’t let their tantrums over privilege drive you into false guilt. And don’t let the secular liturgists of ugliness define what your heart is allowed to love.

We were made to love what is good, true, and beautiful. That includes a well-cut cathedral, a sonata in a major key, a sunrise over the Grand Canyon — and God, who created all of this.

It’s not a crime to recognize beauty. It’s an act of sanity.

Youth retailer American Eagle just launched a new ad campaign featuring “it girl” Sydney Sweeney from “Euphoria” — and her well-endowed fame is turning heads and shaping markets. The campaign launch, featuring the bombshell known for her curves, drove the stock up 15% in a single day.

Whatever American Eagle paid Sweeney, it was worth it. The company’s market cap jumped $400 million in one day following a 47% decline in its stock price last year. After years of hawking body positivity, it appears “hot girl summer” is once again the way to go.

American Eagle is back, reignited by the formula as old as advertising itself: Sexy sells.

The idea that hot girls leaning on muscle cars sell jeans — or anything else, for that matter — is nothing revolutionary in the ad world. Who could forget Pepsi’s 1992 ad featuring Cindy Crawford at the gas station in jeans and a white tank top? No Gen Xer on the planet could forget this ad. It was iconic — and effective.

American Eagle’s newest campaign is a major about-face after more than a decade of jeans, car, and beer brands forcing wokeness down our gullets. Ultimately, sex sells. And pretty girls with sexy stares can sell everything from men’s deodorant to the WNBA — if only they had more Sophie Cunninghams!

Calvin Klein jeans made sexy their stock-in-trade over 40 years ago. In 1980, the premium jeans brand gave us Brooke Shields seductively whispering, “You want to know what comes between me and my Calvins? Nothing.”

She was 15, and it was both sordid and problematic. But it ushered in decades of “hot girls in jeans” advertising. From Kate Moss naked from the waist up in Calvin Klein jeans to Anna Nicole Smith doing her best Marilyn Monroe impression for Guess, the formula worked.

Abercrombie & Fitch gave sexy a twist with preppy hot girls and guys — shirtless — in black-and-white Bruce Weber photography. CEO Mike Jeffries was so obsessed with sexy that the brand was sued for hiring only good-looking people as sales associates in their stores.

Then wokeness tightened its grip on corporate America. Sexy was out. Dylan Mulvaney cosplaying as Audrey Hepburn drinking Bud Light and overweight, nonbinary, hairy-chested men in bras and Calvin Klein jeans were in.

But the public didn’t buy it. Literally.

Bud Light’s partnership with Mulvaney in 2023 sparked a historic backlash. The brand plummeted from America’s best-selling beer to number three. Its market share tanked, and sales have declined more than 20% annually since.

RELATED: Go woke, go MEGA broke — this luxury company’s sales just plummeted 97%

But after years of brand-destroying body positivity, the remnants of normies at American Eagle took the wheel, and their sales and stock price soared. The brand is back, reignited by the formula as old as advertising itself: Sexy sells. Always has, always will.

Even Nike seems to be walking back its own woke phase. Just last week, the company ran a series of ads with U.S. Open winner Scottie Scheffler touting family values.

Another adage permeates advertising: Always include a cutaway shot of either a dog, a baby, or both. Cuteness, like hotness, sells. And nothing is cuter than golf champ Scheffler holding his baby.

Nike’s ad campaign with Scheffler comes on the heels of the company’s previous campaign with Dylan Mulvaney in a sports bra — without any boobs at all. Are we to believe that Nike has shed its wokeness? I think what’s more likely is that Nike was never woke to begin with.

Nike’s mantra is money. And execs will abandon Mulvaney as fast as you can say, “Just do it,” if it means reversing their sales decline and pleasing their shareholders.

As Clay Travis famously put it, “The only two things I 100% believe in are the First Amendment and boobs.” We can gasp and pretend this is a controversial statement. But Travis only said what we all know to be true: Boobs are a reliable winner. Breast augmentation surgeries have experienced a compound annual growth rate of 13% per year since 2020 for a reason.

American Eagle’s Sydney Sweeney campaign is not remotely “body positive,” and that’s a good thing. It pays. And I predict other brands will take note.

Returning to normie marketing means brands can advertise normal ideas to normal people without feeling bad about it any more. And we can let it wash over us in all of its visual pleasantness.

Expect a wave of ad campaigns in which marketers quietly memory-hole the failed “body positivity” experiment and return to what actually works. The brands chasing social justice won’t say it out loud, but they’re breathing a collective sigh of relief.

I was skimming through Substack the other day looking for something of interest to read when I came across an article titled “Where Is Today’s Michelangelo?”

It was a thought-provoking piece about the depleted state of modern society’s artistic soil thanks to the eradication of ideals and objective truth, the rise of mass consumerism, and the decline of humanism.

David’s story is one worthy of the blessed hands of Michelangelo, a story worthy of a legacy that lasts all of human history.

The author argued that we’ve yet to see Michelangelo’s equivalent not because he or she doesn’t exist, but rather because our culture no longer knows how to nurture artists capable of reaching such heights.

To give an analogy, the world’s fastest man might be hiding in a village right now, but if that village is plagued with famine and he cannot eat properly, his muscles will not thicken, his bones will not harden, and his potential will die entirely untapped.

The same principle applies to the Michelangelo-level artist, who requires certain specific nourishment to develop his talent fully.

The article got me thinking about a work of art recently unveiled smack in the middle of Times Square to great acclaim — at least from some circles. Perhaps you’ve heard of it.

Titled “Grounded in the Stars,” this 12-foot bronze sculpture portrays an overweight, average-looking black woman in casual clothing, standing with hands on hips. The artist, Thomas J. Price, sculpted her in contrapposto as a nod to the Renaissance king’s “David” — arguably the most beloved sculpture to ever exist.

A glance at the two works side by side, and it’s easy to see that “Grounded in the Stars” is indeed inspired by “David” — the poses, the intense visages, the prowess both aim to convey.

Yet “Grounded in the Stars” will never — could never — dwell in the same divine orbit as “David.” And nobody with an inkling of sense would ever claim otherwise.

My question, and I think it’s an important one, is why? Why would nobody dare argue that Price’s bronze woman could ever ascend the same Olympian heights as Michelangelo’s “David”?

Is the answer purely technical?

It's true that "David” is more anatomically detailed, with his veined hands and subtly tensed muscles, than “Grounded in the Stars,” which employs a smoother, more stylized surface.

And the technical mastery displayed by “David” is all the more impressive considering the rudimentary tools Michelangelo had at his disposal. He painstakingly hewed his statue by hand from a single block of marble (and a flawed one at that).

Michelangelo had zero room for error. Price, by contrast, may have relied on digital modeling and other modern tools that allowed him to fix mistakes and refine details before casting.

Are these disparities in craftsmanship what creates the gap between these two works?

It doesn’t take an artist or an art critic to know that’s only a fraction of the answer. “David” is hallowed — immortalized in the artistic canon — for reasons that go beyond its objective beauty and precise craftsmanship.

But while the vast majority of people instinctively know "David" is the superior of the two sculptures, I think many, if asked, would struggle to articulate what precisely makes it so. They would likely stutter through generalities — he’s an important part of biblical history; he was created by the great Michelangelo; he’s seen millions of visitors for hundreds of years.

All true, yet shallow and incomplete.

I think as a society we’ve forgotten the elements of greatness. We recognize objectively great art when we see it, but our understanding hardly reaches beyond physical sight. It’s like looking at water but not knowing that hydrogen and oxygen are what make it up.

We know “David” is an emblem of artistic excellence to the highest degree and that “Grounded in the Stars” is not, but do we know the deepest reasons this is true?

If we did, perhaps then we’d be erecting something far better in Times Square today. For that to be a possibility, though, modern culture has to relearn the chemical makeup of greatness.

Comparing these two statues is as good a place as any to start.

The Renaissance, the period in which Michelangelo sculpted “David,” was a revival of classical antiquity — specifically the art, literature, philosophy, and culture of ancient Greece and Rome.

This culture came with certain ideas about artistic legacy and permanence, ideas that drove Greece’s Parthenon sculptors as much as the artists of Augustus’ Rome.

Just as you and I tend to measure the impact of digital content by its virality (how widely it spreads), Renaissance artists understood that their works, if they achieved excellence, would endure in human history. Generations of people would come and go, ages would wax and wane, empires would rise and fall, and yet their art would survive it all — save natural disasters and angry mobs.

And so when Michelangelo took on the herculean task of “liberating” David from the 18-foot block of Carrara marble that had already been deemed unworkable by two other sculptors, he knew the weight of his task.

He wasn’t just creating a stone replica of a historical figure. He was making history himself. He understood that “David” would transcend the moment of his creation; like all great religious art of the Renaissance, "David" was intended to guide the consciousnesses of spectators for centuries to come.

And the sculpture has done exactly that. It’s been 521 years since the completion of "David," and the figure still receives several thousand visitors per day. But why? What is it that makes it worthy of such a legacy? "David" is inarguably beautiful; in fact, Michelangelo carved him to represent the ideal male form — a concept rooted in Renaissance humanism.

But this is not solely what gives “David” his longevity.

There’s a reason beauty and truth always seem to go hand in hand. It is, of course, the virtues “David” represents that immortalize him. "David" is marble courage, heroism, and moral resolve. His narrative is one of civic virtue, triumph over tyranny, and unwavering faith in God.

He originates and exemplifies the victorious underdog — a concept we are still cheering millennia later. We do this because we are all underdogs in some capacity. Goliath looms in our homes, our workplaces, even our own hearts; Philistine armies are always rising up and casting shadows. Each of us has been a shepherd caught up in a war we didn’t ask for.

David’s courage to say I will go imbues us (even those of us who reject the God from whom David’s courage came) with fortitude to face our own giants.

In this way, David’s story is all of our stories. And as long as there are giants and people with the will to challenge them, it will live on.

Whose story does “Grounded in the Stars” tell? The title certainly connotes beauty, strength, and legacy.

But no — this is no one’s story. The artist has told us so himself.

“The work is a composite fictional character, unfixed and boundless, allowing us to imagine what it would be like to inhabit space neutrally without preconceived ideas and misrepresentation,” Price said of his sculpture.

So not only is this a statue of nobody with no story to tell, that is precisely the point. Price urges us to reject excellence and instead celebrate mediocrity — to cheer not because someone is virtuous, heroic, saintly, or accomplished, but because she is supposedly marginalized.

What a hopeless message.

For the truly marginalized, the statue doesn’t speak to their sense of strength or resilience; it doesn’t encourage them to rise above circumstance, carry their burdens with courage, or to even hope for better days.

It says the opposite — sit in your victimhood; let it crystalize into bitterness. Wear it like a badge of honor; wield it as a weapon.

Such a message robs marginalized people of the very tools needed to emerge from the station they want to escape. It’s tokenism packaged as empowerment, keeping them down but convincing them they’ve risen.

And to those who would be considered privileged, the statue is a condemning lecture — a “shame on you,” finger-wagging political rant in the form of a looming bronze woman that looks and feels like a modernized idol from ancient days.

If the goal is to help the fortunate see the plight of the downtrodden, this does the opposite, sowing more divisiveness and resentment. No one ever comes to see the light through shame.

And here’s my biggest question: Which statue better honors the marginalized? Before he was king, David was a shepherd — one of the lowliest groups in biblical history, barely above beggars and outcasts. Remote field work kept shepherds on the literal fringes of society, far removed from urban centers. Their status as humble laborers ensured that they lacked power and influence. They were poor, uneducated, and dirty from working with animals.

On top of that, David was young at a time when a man’s age was indicative of his worth, especially as a warrior. From every angle, he was unfit to face Goliath.

But no matter. Faith and courage rooted in God would be his wings.

And they were, from the moment he slung the fatal stone to the moment of his crowning as the king of Israel.

There is no better story of a marginalized person rising to greatness than David’s. It’s a story worthy of the blessed hands of Michelangelo, a story worthy of a legacy that lasts all of human history.

Price’s nameless bronze woman, by contrast, is rooted in the fleeting values of modern DEI and identity politics, unlikely to outlast her creator.

Come June, the statue will be removed from its temporary post in Times Square and whisked away to some private gallery or worse — to storage. There, it will meet the same sad fate as the majority of contemporary art. Its impact will be but a ripple in a pond that quickly fades and is forgotten.

But I don’t necessarily place the blame on Price. To quote the article I mentioned above, “a culture starved of deep convictions is shallow soil, unconducive to the growth of great artists.”

If we want to produce great art again, we have to cultivate values that strengthen the human spirit, calling us out of darkness and into light — whether we are marginalized or privileged.

Only then will we create art that is truly grounded in the stars.