Scott Adams made Trump plausible before anyone else would

On the timeline of making America great again, two dates in 2015 stand out for anyone who backed Donald Trump before it was safe to do so.

On June 16, 2015, Trump came down the escalator in New York City and announced his run for president. The political class laughed. Conservative pundits mocked him. Commentators treated the whole thing as a stunt. A lifelong Democrat running as a Republican? A celebrity billionaire developer? Please. What a “clown.”

Scott understood something most people never learn: Bad reviews from bad people are good reviews. He also understood how to grieve with honor instead of self-pity.

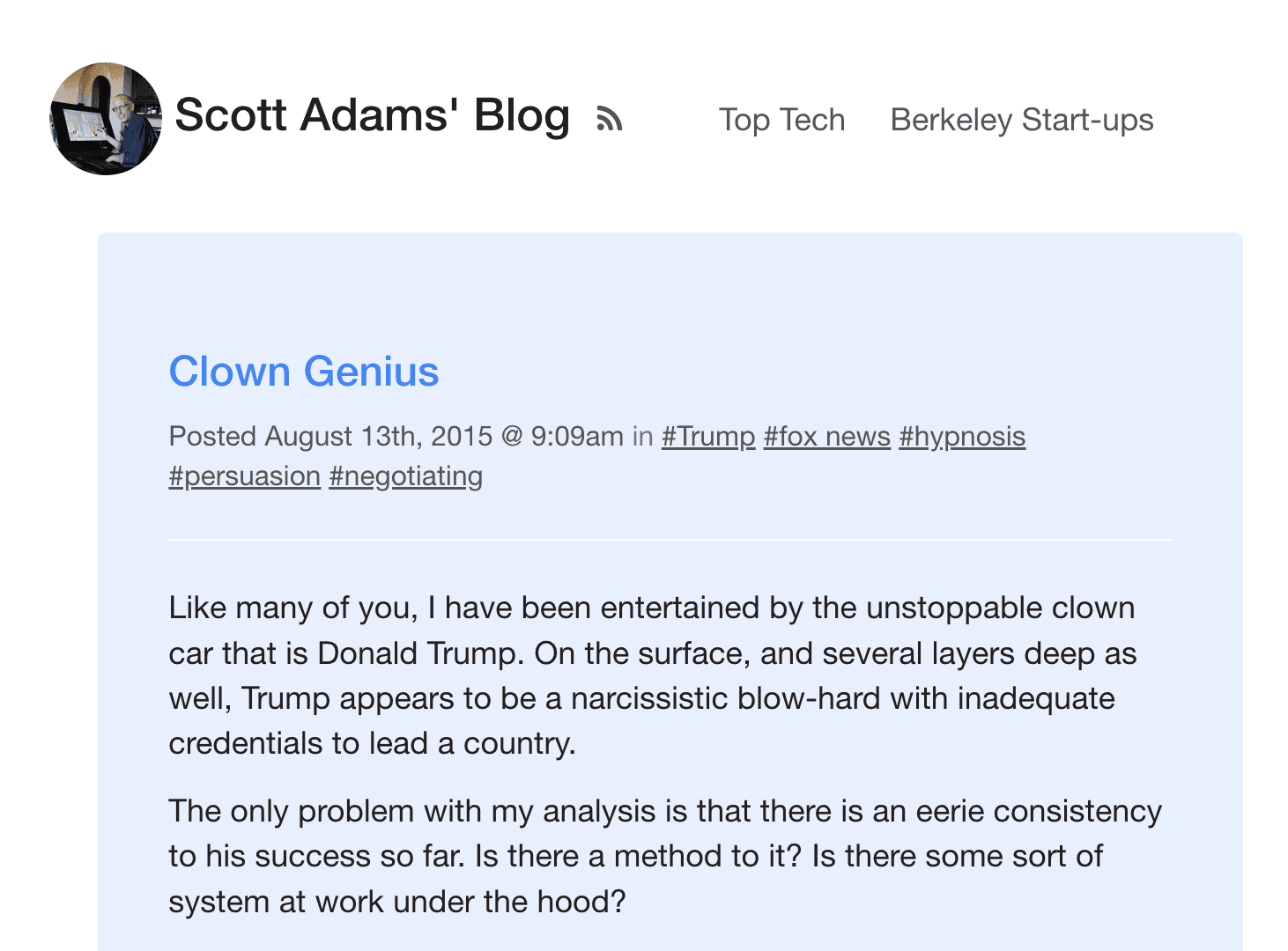

Then came August 13, 2015.

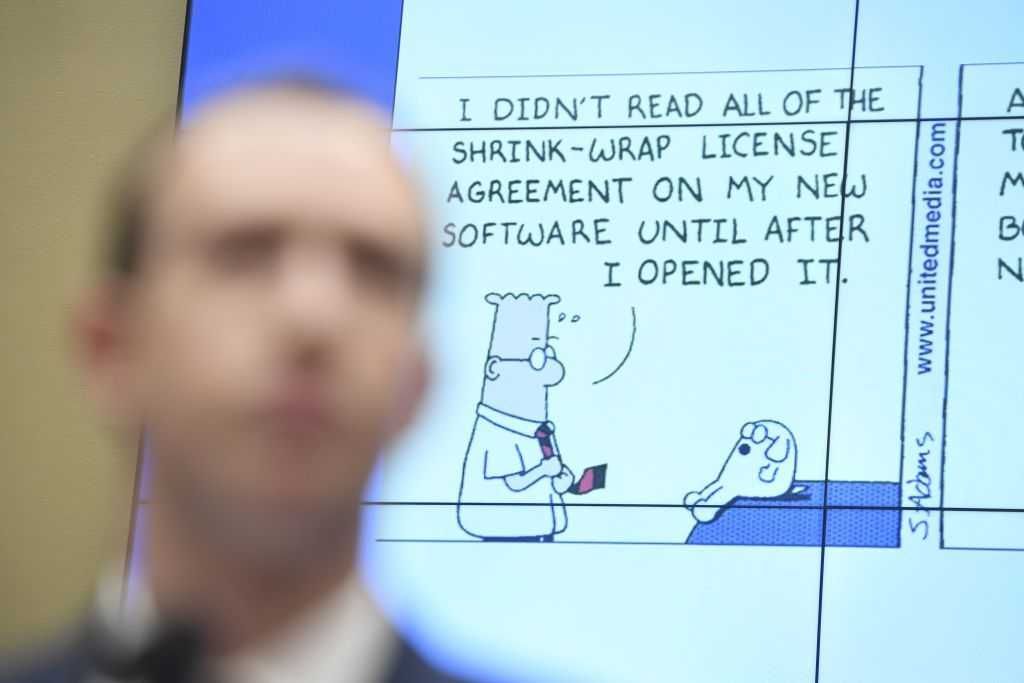

That day, Scott Adams — the creator of “Dilbert” and a best-selling personal development author — published a blog post that reframed the entire race in a single phrase:

Usual frame:

Donald Trump is a clown.

Reframe:

Donald Trump is a clown genius.

That was Adams’ title: “Clown Genius.” And his point was simple: Trump wasn’t improvising. He was persuading. Adams wrote that Trump’s “value proposition” was to “Make America Great,” which meant selling the world on America again — what Adams called “good brand management.”

It sounds obvious now. It didn’t sound obvious then.

Adams became one of the first major nonpolitical public figures to say out loud what millions of Americans were starting to suspect: Trump wasn’t a joke. The joke was the people pretending they couldn’t see what was happening.

That post didn’t just defend Trump. It gave people permission. It gave tens of millions of everyday Americans cover to voice support for the one candidate the establishment of both parties hated more than anyone they had seen in decades. Adams called it before the polls did, and he kept calling it.

And, in the process, he helped change the course of human history.

He later packaged Trump’s persuasion methods into a book-length case study, “Win Bigly.” And famously, he assigned Trump a 98% chance of winning in 2016 — at a time when most of the media treated the idea as laughable.

Adams paid for that courage.

When he backed Trump in 2015, he didn’t just lose polite invitations. He lit his career on fire. He traded lavish speaking fees, safe corporate fame, and establishment approval for permanent exile from respectable opinion.

In October 2025, Adams described the price in stark terms:

When I decided ... to back Trump … I sacrificed everything. I sacrificed my social life. I sacrificed my career. I sacrificed my reputation. I may have sacrificed my health. And I did that because I believed it was worth it. … I’m really happy I lived long enough to see it. It was worth it. … It was worth it to be right.

Independent journalist and filmmaker Mike Cernovich made the point even more bluntly. Adams could have kept quiet, kept the corporate speaking gigs, and died richer. Instead, he chose the lonely road and earned something bigger than money. He became a legend.

For millions, Scott Adams was more than a cartoonist or a commentator. Worldwide, listeners of Scott’s daily show, “Coffee with Scott Adams,”knew him as our “internet dad.” If Trump is the father of MAGA, Scott is its honorary stepfather.

People didn’t just read him. They listened to him. They learned from him. They built confidence from his willingness to say what others wouldn’t.

President Trump made America great again. Scott Adams made Candidate Trump plausible in the first place.

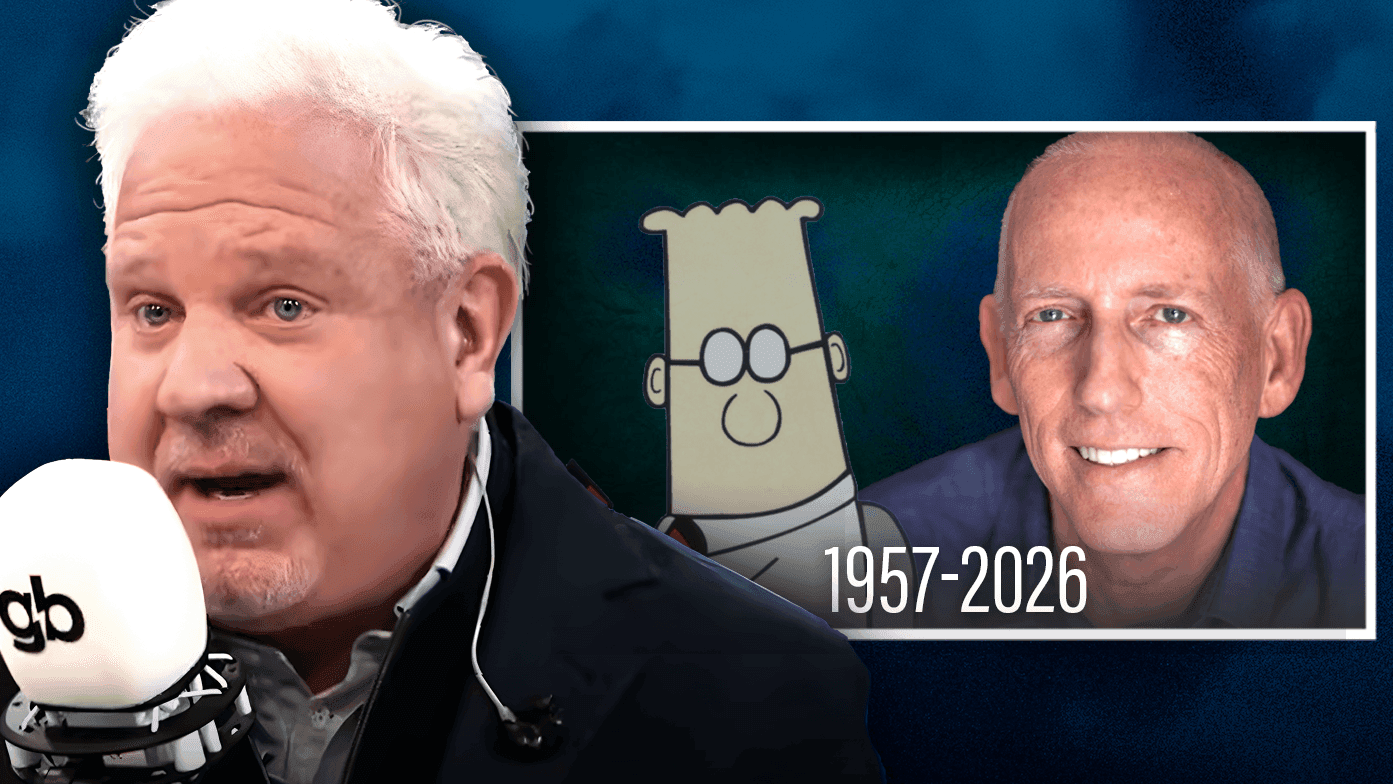

After a long, public battle with prostate cancer, Scott Adams died on Tuesday, January 13. He was 68.

President Trump responded with a tribute that said more than many will admit.

— (@)

“Sadly, the Great Influencer, Scott Adams, has passed away. He was a fantastic guy, who liked and respected me when it wasn’t fashionable to do so. He bravely fought a long battle against a terrible disease. My condolences go out to his family, and all of his many friends and listeners. He will be truly missed. God bless you Scott!”

I’m one of those listeners and friends. More than that, I was Scott’s editor, and I remain the publisher of the Scott Adams library. He brought me on as a contributing editor for “Reframe Your Brain,” a book that has helped thousands of readers apply his signature “reframes” to work, money, relationships, and even faith.

As of this writing, “Reframe Your Brain” is the No. 1 best-seller on Amazon.

RELATED: Glenn Beck remembers Scott Adams: ‘A philosopher disguised as a stick-figure artist’

Near the end of his life, Scott also made a quiet but meaningful choice. He accepted Pascal’s Wager — the simple risk-reward logic that faith in Jesus Christ is worth the bet. He pinned that profession to the top of his X.com profile in his final statement.

Scott was a father figure to me in the most practical sense. I asked his advice the way a son asks his dad. He was happy to oblige. That’s who he was: sharp, funny, and eager to be useful.

Now critics will rush in to re-litigate his controversies, including the 2023 livestream that helped get “Dilbert” pulled from newspapers. I wrote the truth for Newsweek at the time, after his remarks triggered an organized effort to kill his book deal and erase him from public life.

I worked with an author on a not-quite-banned book recently. Dilbert creator and bestselling author Scott Adams had his long-running comic strip ended by multiple newspapers and his forthcoming book contract canceled over some hyperbolic remarks on race that were intended to stir up discussion. Scott Adams’ books were twice banned, but Amazon reversed the decision. … Adams then went to his audience and let them know that there were people who didn’t want his book published, and they responded by buying it, en masse. Sales shot up.

Scott understood something most people never learn: Bad reviews from bad people are good reviews.

He also understood how to grieve with honor instead of self-pity. As he wrote in “Reframe Your Brain”:

When you experience the death of a loved one, your instincts push you into feeling tragedy, loss, and pain. Once you have had enough of that, and when you are ready, start tossing these five words around to release some of the pain: Gratitude. Respect. Honor. Privilege. Service.

Scott Adams lived those words. And now he belongs to the ages.

Scott won bigly.

Thank you, Scott.

SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images

SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images

amphotora / Getty Images

amphotora / Getty Images

Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images

Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images Photo by HANNAH MCKAY/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

Photo by HANNAH MCKAY/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

Mirrorpix/Getty Images

Mirrorpix/Getty Images

Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call Inc. via Getty Images

Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call Inc. via Getty Images

Levin: Precedents and presidents, the left's relentless campaign against Trump