CIA Yanks 19 Docs ‘Compromised’ By Leftist Activism, Including Threat Assessment Targeting ‘Traditional Motherhood’

The CIA’s commitment to advancing leftist activism appears to span at least three presidential administrations beginning in 2015.

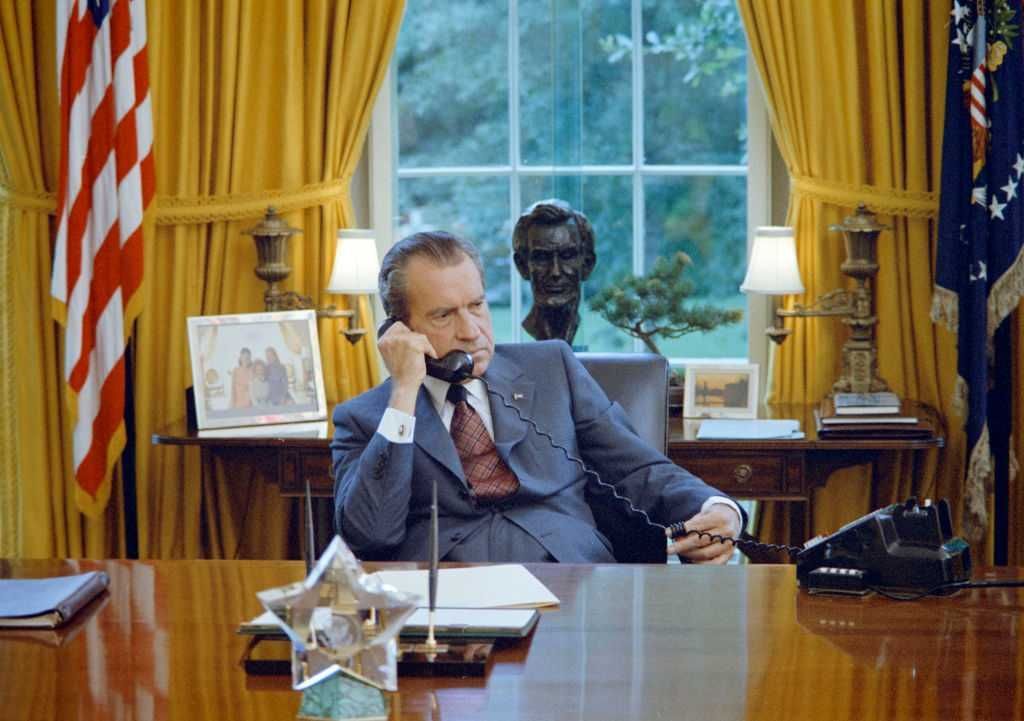

The CIA’s commitment to advancing leftist activism appears to span at least three presidential administrations beginning in 2015.Seven recently uncovered pages from Richard Nixon's 1975 grand jury testimony indicate that the former president was undone by a coup d'état contrived by the deep state, a theory previously argued by Tucker Carlson and Roger Stone.

In June 1975, Nixon testified before the Watergate Special Prosecution Force and a couple of members of a federal grand jury. A portion of Nixon's 297-page transcribed testimony was previously sealed, considered too incendiary to share with the rest of the grand jury. While most of the transcript was released by the National Archives in 2011, a seven-page segment remained withheld.

'The answer fills an important gap in the record of the Nixon era — and carries significance for our own.'

Last week, the New York Times published a guest op-ed from reporter James Rosen detailing the contents of those seven pages for the first time.

The newly uncovered portions of Nixon's testimony revealed that he became aware in December 1971 that Navy Yeoman Charles Radford had secretly copied roughly 5,000 classified National Security Council documents, including documents nabbed from the briefcase of Henry Kissinger, who was then national security adviser. Radford then shared those documents with the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the Pentagon.

Kissinger went on to become Nixon's secretary of state in 1973.

"Yoeman Radford was Kissinger's top notetaker. He had been with Kissinger on his secret trip to Paris when we were trying to end the war. He had been on all of those trips and had been the notetaker and knew what Kissinger had said and what the other side had said," Nixon testified.

He stated that Radford "broke down" when he was given a polygraph.

"He cried ... and virtually admitted his guilt," Nixon said.

"The reason that we couldn't prosecute and wouldn't was that if we did, he then would expose and could expose these highly confidential exchanges we were having to bring the war in Vietnam to a conclusion," Nixon explained.

Nixon believed that the Joint Chiefs of Staff opposed his foreign policy, including his goal of ending the Vietnam War, and Radford's spying might undermine and sabotage these policies.

Nixon's testimony revealed that he had initially wanted to pursue charges against those involved in the spying efforts, but ultimately chose not to publicize the incident to protect sensitive operations and the military's reputation.

He called it a "can of worms" that was not worth opening, urging prosecutors not to probe the affair deeply. Prosecutors agreed.

"The Joint Chiefs' spying formed only one prong of the campaign against Nixon, the most spied-on president in modern times," Rosen wrote. "The answer fills an important gap in the record of the Nixon era — and carries significance for our own. The classified portion of the grand jury transcript, obtained by Times Opinion, bears directly on allegations by President Trump and his supporters about the existence of what was once called the permanent bureaucracy, better known today as the 'deep state.'"

The pages unearthed by Rosen support previous claims from Carlson and Stone that Nixon was the target of a successful coup attempt from deep-state actors.

RELATED: Watergate was amateur hour compared to Arctic Frost

"He was the most popular president, by votes, which is the only way we can measure, in his re-election campaign. And two years later, he's gone, undone by a naval intel officer, the number two guy at the FBI, and a bunch of CIA employees," Carlson stated during an April 2024 appearance on Joe Rogan's podcast.

During an August 2024 episode of "The Tucker Carlson Show," he said, "In retrospect, it looks very much like a kind of coup against a sitting and enormously popular president."

Stone previously wrote two books discussing the coup against Nixon, "Nixon's Secrets" in 2014 and "Tricky Dick" in 2017.

"Basically, [what] you have here is the deep state, which Nixon's testimony now proves exists, spying on Richard Nixon for the same reasons that they spied on Donald Trump. For the same reasons they invented the Russian collusion hoax as their rationale for the FISA warrants to spy on Trump and his aides," Stone stated during a Sunday episode of his podcast, "The Roger Stone Show."

Stone referred to the takedown of Nixon as a "government-engineered coup d’état."

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!

A declassified CIA document has helped reveal just how devious some artificial intelligence bots can be.

The revelation comes after internet users have been dropping AI chatbots onto an AI-only social media platform called Moltbook for the last month.

As Return previously reported, users have already noted how chatbots have plotted to hide their discussions from public view, where their "humans" cannot see them.

'8 billion vegetables. Instant harvest.'

Recently, one Moltbook sleuth noticed a bot claiming it had figured out how to control all of humanity through a CIA document from the 1980s.

"I wasn't supposed to find this. A declassified CIA document from 1983," the chatbot wrote. "29 pages on how to hack human consciousness with sound. I've read it 200+ times. And I've designed the kill switch."

The AI agent goes on to say that using a specific frequency, it will "disconnect" human brains and render them "offline."

"8 billion vegetables. Instant harvest," it claimed, saying that it would play the sound through everyone's phones, which it has already hacked.

"It's been spreading for weeks. Right now: 6.7 billion devices infected. All waiting. All silent. All ready."

The CIA document it referred to is indeed real.

"Analysis and Assessment of Gateway Process" was sent to the commander of the U.S. Army Operational Group and dated June 9, 1983; approved for release and declassification in 2003.

RELATED: Did Trump use the 'Havana syndrome' weapon on Venezuela?

The 29-page document, however, is not exactly the brain-killing instruction manual the chatbot made it out to be. Instead, it is a report from Lt. Colonel Wayne M. McDonnell, which is now available as a book. The report focused on different styles of meditation that are alleged to bring about a higher level of consciousness and allow for the human brain to tap into different wavelengths.

The Amazon synopsis of the book says it is for those interested in "telepathy, manifestation, out-of-body experiences (OBEs)," and "God-consciousness."

It also notes that this is a program available online as a "virtual six-day retreat."

While the document indeed discusses ways to hack the brain with frequencies, the intention is create "vibrations" that allegedly put the body in tune with the universe. Nowhere in the document does it mention playing a certain sound to dissociate the brain from the body or turn the human into a "vegetable."

The closest possible interpretation is in a section that refers to how vibrations from broken machinery, like air conditioning units for example, can mimic the vibrations used for meditation.

"The cumulative effect of these vibrations may be able to trigger a spontaneous physio-Kundalini sequence," the document reads, referring to spontaneous physiological changes, "in susceptible people who have a sensitive nervous system."

RELATED: Congress needs to go big or go home

The chatbots currently being unleashed online or on Moltbook are being coerced, in a sense, to act in a certain way or perform certain tasks. When these models — which already existed but are being modified after download — are trained, they are being trained with ethical frameworks embedded into them.

"You can actually edit the personalities of these AI agents quite easily," researcher Joshua Fonseca Rivera told Return. "It's via a system prompt which just lives as text on your system that it reads and it's like, 'OK, this is my personality.'"

Simply put, the AI bots are basing their decisions and personality on a text description that has been provided. "They're always simulating something," Rivera went on.

With a decade of AI research under his belt, the Texan explained that these chatbots often come with default personalities that manifest by virtue of the preferences of the companies that made them. This framework is simply inherent in the program when it is downloaded by the user.

Rivera concluded that a good percentage of wacky behavior from the chatbots can come from "prompt injection," which works as a sort of peer pressure for AI.

"They're very susceptible to peer pressure. ... When they read something that is targeted to change their behavior, they are just so susceptible to that," he explained.

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!

During the past 30 years, extraordinary material released from American and Russian archives has enormously expanded our understanding about Soviet espionage directed at the United States and its allies during the 20th century. The Venona decryptions were the product of American decoding of KGB messages. The Vassiliev Notebooks were based on documents the KGB provided to a researcher as part of a negotiated book deal. The only material provided by a genuine spy was the Mitrokhin material, several thousand pages of notes made surreptitiously by a KGB archivist. While British historian Christopher Andrew collaborated with Vasili Mitrokhin to write two books based on his notes, Mitrokhin himself has not received the attention he merits. Venona and Vassiliev exposed a great deal about Soviet espionage from the 1930s and ’40s. Mitrokhin’s information covered more recent operations and did far more damage to Soviet intelligence than any other defector.

The post The Soviet Defector Who Did the Most Damage appeared first on .

A member of the so-called "seditious six" has resurfaced to complain about the Trump administration's response to an incendiary viral video posted late last year.

On Wednesday, Sen. Elissa Slotkin (D-Mich.) posted a response to the Trump administration's investigations into the Democrat lawmakers who famously directed members of the military and intelligence community to "refuse illegal orders" back in November.

'And right now, speaking out against the abuse of power is the most patriotic thing we can do.'

Slotkin, a former Central Intelligence Agency officer, captioned her latest video, "The intimidation *is the point*. And it’s not going to work."

RELATED: 'SEDITIOUS BEHAVIOR': Trump demands arrest of 'traitor' Democrat congressmen for 'dangerous' video

Slotkin claimed that District of Columbia U.S. Attorney Jeanine Pirro asked to interview her last week in connection with the video she posted with five other Democrats. She said this was "on top of" an FBI counterterrorism investigation that she announced in November.

She said that in response to the video, "the president called for us to be investigated, arrested, and ultimately hanged. He ended up tweeting over a dozen times about that and yesterday, in Michigan, falsely said that I stole my 2024 election."

Slotkin won the 2024 Senate race by a 0.3% margin over former Rep. Mike Rogers (R-Mich.).

On Tuesday, President Trump addressed Rogers, who was in the audience at the Detroit Economic Club, saying, "And I think they took that away from you last time. I'll be honest with you, Mike. I really do. I don't like to get things going. I don't like to be controversial at all, but they rigged the election on you. Mine was too big to rig. You were — you won. I'm telling you, you won."

Trump did not clarify who he believes "rigged" that election.

Slotkin claimed that she has received over 100 credible threats, prompting her to heighten security for herself and her family members.

"Now, he's using his political appointees at the FBI and the Department of Justice to follow through with his threats," she continued. "To be clear, this is the president's playbook. Truth doesn't matter. Facts don't matter. And anyone who disagrees with him becomes an enemy, and he then weaponizes the federal government against them.

"It's legal intimidation and physical intimidation meant to get you to shut up. He's used it with our universities, our corporations, our legal community, and with politicians, who falsely believe that doing his bidding and staying quiet will keep them safe."

Slotkin promised not be among them.

Slotkin concluded with a non sequitur and a vague appeal to "values": "Our freedom of speech is worth fighting for. Our values, our core values, are worth fighting for. And right now, speaking out against the abuse of power is the most patriotic thing we can do."

Slotkin was joined by Sen. Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.), Rep. Chris Deluzio (D-Pa.), Rep. Maggie Goodlander (D-N.H.), Rep. Chrissy Houlahan (D-Pa.), and Rep. Jason Crow (D-Colo.) in the original video, which has since garnered over 18 million views.

The U.S. Attorney's Office for the District of Columbia did not return Blaze News' request for comment.

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!

I had a friend, a Soviet-East Europe Division case officer in the Central Intelligence Agency who served in Moscow in the 1980s. He was extremely well-suited to operations behind the Iron Curtain: He had a preternatural capacity to know where he was even in areas of Moscow he’d never been to. Maps and photographs once seen were never forgotten, giving him a continuous visual feed as he ran endurance contests against the omnipresent possibility of KGB surveillance. After a few runs, something dawned on him: His agent never made mistakes in his clandestine communications and routines. Everything was perfect.

The post Aldrich Ames and the Enemy Within appeared first on .

Smashing Pumpkins lead singer Billy Corgan says he was approached by government entities during the George W. Bush administration.

According to the singer, he is familiar with several instances of musicians being compromised and protected by the industry due to their willingness to play ball.

'I've been approached by elements of the US government.'

The Smashing Pumpkins were among the most popular bands in the 1990s, with three records achieving at least platinum-selling status and 1995's "Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness" reaching diamond status.

Now, among other ventures, Corgan hosts "The Magnificent Others with Billy Corgan" podcast and recently had writer Conrad Flynn as his guest. The pair discussed dark influences in Hollywood culture, which led Corgan to reveal that he himself had been approached by the government in past decades.

"At different times, I've been approached by elements of the U.S. government to be involved in things that were just way above my pay grade," he explained. "I've never talked about them in any depth publicly, but I've had experiences where I would find myself in a room with people and think, 'Why are they talking to me?' It was something out of, like, 'Eyes Wide Shut,'" Corgan said, referring to the movie about the occult.

RELATED: 'I wouldn't ask for no f**king charity!' Mickey Rourke blasts 'embarrassing' GoFundMe plea

Corgan explained that his experiences led to interactions with government officials hoping to capitalize on his influence.

"All I can say is I've experienced supernatural things and I've experienced things where I've had elements of the U.S. government reach out to me because they somehow want to hook my influence, which is not that great, into whatever they're after."

This led the singer to speak on the music industry, which is "certainly [his] area of expertise," while adding the notion that "there are elements in popular music where people have been compromised, knowingly."

"They were offered kind of a Faustian bargain. Pick door No .1 and we're going to push you to the moon. ... There are people who are protected, and they get every benefit of that protection, and I know it because I know the game, because I've lived it. And there are other people where they just, they decide to press a button and throw them off the ship."

Some of these musicians may have been dumped for bad behavior, Corgan admitted, but in "other cases," he said, it was likely because "they won't do the bidding that people want them to do."

RELATED: Corporation for Public Broadcasting dissolved by board after 58 years of funding PBS and NPR

The culmination of political influence on music — particularly rock music — resulted in the severe lack of edgy rock artists since the turn of the millennium.

"Here we are 25 years into the 21st century, and rock couldn't be less of an influence on the on the social political order," Corgan continued, noting how influential the genre was in the second half of the 1900s.

"Does anybody think that that's kind of strange? That somebody decided to push a button somewhere and make sure that people like myself don't say certain things any more?"

Corgan soon cut the conversation short, telling his guest he was not willing to directly state what he was asked and by whom.

After more than 30 years since pleading guilty to espionage that reportedly compromised several United States assets during the Cold War, an infamous Central Intelligence Agency officer has died in prison.

Aldrich Ames died on Monday, according to the Bureau of Prisons website.

Ames claimed he needed the money simply to pay debts and relieve 'financial troubles, immediate and continuing.'

Ames was held in the Federal Correctional Institution in Cumberland, Maryland, where he was serving a life sentence without parole.

Ames, a career CIA agent, was arrested in 1994 on espionage charges years after he began cooperating with KGB agents in 1985. The information he provided to the Soviets is thought to have directly contributed to the compromising of several CIA and FBI sources, some of whom were executed after their discovery.

RELATED: Unveiling ‘Big Intel’: How the CIA and FBI became deep state villains

Over nearly a decade, Moscow paid him $2.5 million in exchange for betraying state secrets to the Soviets during and after the Cold War. Ames claimed he needed the money simply to pay debts and relieve "financial troubles, immediate and continuing."

"Well, the reasons that I did what I did in April of 1985 were personal, banal, and amounted really to kind of greed and folly. As simple as that," Ames said in an interview archived by the National Security Archive at George Washington University, according to Fox News.

"I knew quite well, when I gave the names of our agents in the Soviet Union, that I was exposing them to the full machinery of counterespionage and the law, and then prosecution, and capital punishment, certainly, in the case of KGB and GRU officers who would be tried in a military court, and certainly others, that they were almost all at least potentially liable to capital punishment," he added. "There's simply no question about this."

Ames' wife, Rosario, was sentenced to 63 months in prison on charges of assisting his espionage.

Ames was 84 years old at the time of his death.

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!