Why California’s ‘model state’ is a warning, not a goal

California’s economic, academic, media, and political establishment still embraces the notion of the state’s inevitable supremacy. “The future depends on us,” Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-Calif.) said at his first inauguration, “and we will seize this moment.” Others see California as deserving and capable of nationhood — a topic that has resurfaced with President Donald Trump’s presidency, as it reflects, in the words of one New York Times columnist, “the shared values of our increasingly tolerant and pluralistic society.”

Critics say this vision is at odds with the facts on the ground. Rather than the exemplar of a new “progressive capitalism” and a model for social justice, California both accommodates the highest number of billionaires and the highest cost-adjusted poverty rate. It has the third-highest gap, behind just Washington, D.C., and Louisiana, between middle- and upper-middle-income earners of any state. Nearly one in five Californians — many working — live in poverty (using a cost-of-living adjusted poverty rate); the Public Policy Institute of California estimates another one in five live in near-poverty — roughly 15 million people in total.

Barely one in three state residents consider California a good place to achieve the American dream. Increasingly, California is where this dream goes to die.

“California” is a model that no longer delivers. Sure, California has a huge gross domestic product, paced largely by high real estate prices and the stock value of a handful of huge tech firms. It retains the inertia from its glory days, particularly in technology and entertainment, but that edge is evaporating as tech firms flee the state and Hollywood productions are shot around the world. For all its strengths, California has the nation’s second-highest rate of unemployment, with lagging job growth, particularly in comparison to its neighbors and chief rivals — notably Texas, Arizona, and Nevada.

The signs of failure are evident on the streets. Roughly half the nation’s homeless population lives in the Golden State, many concentrated in disease- and crime-ridden tent cities in Los Angeles or San Francisco. Barely one in three state residents — and only one in four younger voters — now consider California a good place to achieve the American dream. Increasingly, California is where this dream goes to die.

‘San Francisco gentry liberalism’

The roots of California are long and deep. In August, for example, the New York Times reported how its development into a one-party state controlled by progressive Democrats has made it the country’s center of political corruption.

“Over the last 10 years,” the Times reported, “576 public officials in California have been convicted on federal corruption charges, according to Justice Department reports, exceeding the number of cases in states better known for public corruption, including New York, New Jersey, and Illinois.”

Ironically, the state’s corruption and decline have been expressed through policies long touted as symbols of progressive enlightenment and virtue — the odd marriage of oligarchal wealth and woke political consciousness some describe as “San Francisco gentry liberalism.”

Under this regime, personified by Newsom and former Vice President Kamala Harris (D-Calif.), progressivism has lost its historic embrace of upward mobility and replaced it with an ideology obsessed with race, gender, and climate. It has produced a political leadership class that, for the most part, is largely made up of longtime government or union operatives. In the legislature, the vast majority of Democrats have little to no experience in the private sector. The failure may have been accelerated by the secular decline of the once-powerful Republican Party over the past two decades. This decline removed the incentives for Democrats to concern themselves with moderate voters of either party.

This development represents a distinct break even with California’s pro-growth progressive past, which helped make the Golden State a symbol of American opportunity, innovation, and prosperity. The late historian and one-time state librarian Kevin Starr observed that under the governorship of Democrat Pat Brown in the late 1950s and early 1960s, California enjoyed “a golden age of consensus and achievement, a founding era in which California fashioned and celebrated itself as an emergent nation-state.” In 1971, the economist John Kenneth Galbraith described the state government as run by “a proud, competent civil service,” enjoying some of “the best school systems in the country.”

This may seem something like ancient mythology to most Californians today. If the builder Pat Brown was an exemplar of “Responsible Liberalism,” California’s government today has been ranked by Wallet Hub as the least efficient in delivering services relative to the tax burden. Pat Brown’s son, Jerry, the Democratic governor from 1975 to 1983 and then again from 2011 to 2019, and his successor, Gavin Newsom, epitomize the triumph of ideology over effectiveness. Theirs is a kind of performative progressivism that shrugs about things like roads that are now among the nation’s worst, a high-speed bullet train plagued with endless delays and massive cost overruns, and a failure to boost critical water systems in a perennially drought-threatened state.

In exchange for all this, the progressive regime has stuck ordinary Californians and businesses with some of the nation’s highest taxes and greatest regulatory burdens. California’s business climate is rated at or near the bottom in most business surveys. The Tax Foundation’s 2019 State Business Tax Climate Index, which evaluates taxes in five categories, also lists California at No. 49, with only New Jersey trailing.

These policies have made California exceptionally expensive for both businesses and households. Indeed, according to current estimates, only Hawaii and Massachusetts have a higher cost of living. California has the highest average housing costs, the second-highest transportation costs, and the third-highest food expenses in the country. Much of this is invisible to the top 20% and 5% of California households, who enjoy median incomes of $72,500 and $129,000 — greater than their national counterparts — but is widely felt in the state’s less affluent areas.

Pell-mell into climatism

California progressivism today embraces many causes — undocumented immigrants, transgender kids, reparations for slavery — but nothing has shaped the state’s contemporary politics more in recent years than a commitment to what Newsom described in 2018 as “climate leadership.”

In embracing the catastrophism that defines climate change as an existential threat to life on the planet, Newsom has left behind the old progressive notion of focusing on materially improving people’s lives by embracing inherently uncertain computer models predicting danger.

In California, experts from what Bjorn Lomborg, a leading skeptic of climate catastrophism, calls “the climate industrial complex” provide the justification for staggeringly expensive, socially regressive mandates based on the conjured models. The state mandates greenhouse gas reductions but leaves implementation in the hands of state agencies closely aligned with the green lobby.

This allows the legislature to look the other way as state climate policies knowingly increase poor and working family costs and shift billions of dollars to the wealthy in the relentless pursuit of unilaterally modeled carbon emission targets that even advocates admit cannot possibly “fix” the global climate. Indeed, in 2023, the California Air Resources Board belatedly disclosed that current state climate policies would disproportionately harm households earning less than $100,000 per year while boosting incomes for those above this threshold.

Newsom’s dogged emphasis on climate change — and achieving “carbon neutrality” by 2045 — has meant massive subsidies for wind and solar, mandates to reduce personal car use by nearly three times the temporary cuts caused by pandemic lockdowns, electrification of home appliances at a cost of many thousands of dollars per household, and even cuts to dairy and livestock emissions with technology mandates, accelerating the relocation of these food producers to other states and increasing food prices.

To justify the pain, state regulators estimated that paying for these changes today would prevent future climate damage, all of which depends on highly uncertain projections spanning, in some cases, hundreds of years in the future. The problem is that even if damage projections are remotely accurate, California’s climate law recognizes that the state cannot affect the global climate unless everyone else in the world follows suit. In fact, global emissions are rising, especially from China, which exported over $120 billion in goods and services, notably manufactured goods, often produced with coal, to California in 2023.

Also based on “expert” opinion, the state has embraced a policy to force people to buy electric vehicles by 2035 — a policy increasingly questionable amid slowing demand for these vehicles. Once again, state officials relying on speculative projections proclaim that the policy will benefit the state’s consumers and the environment — although this seems questionable, given, as Volvo suggests, the energy demands of building such cars may take years to have a positive impact.

The price of climate delusion

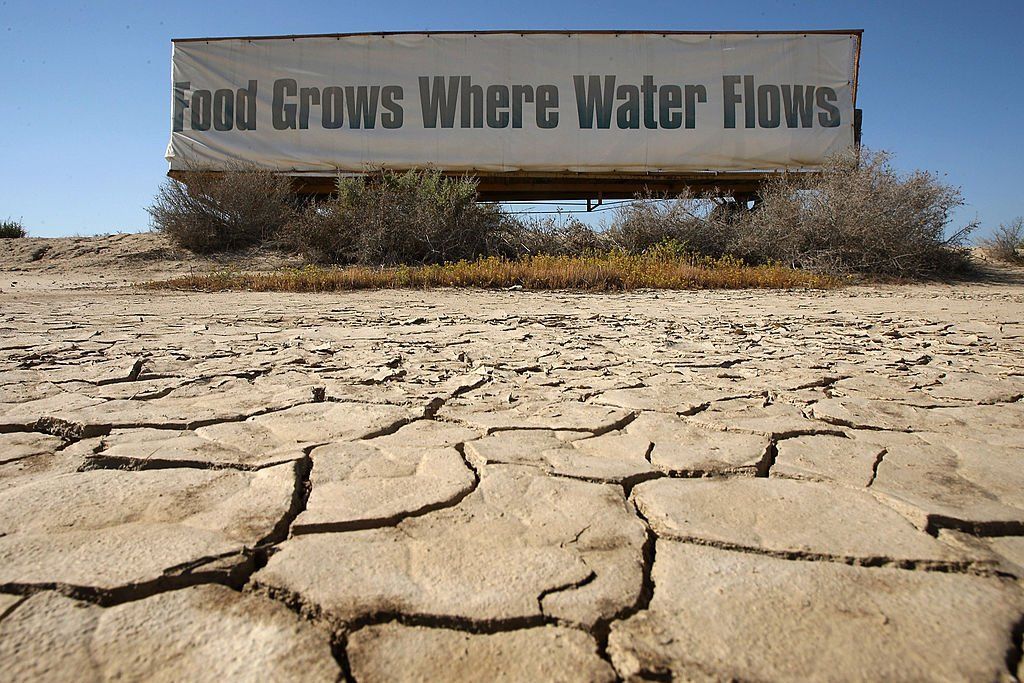

The recent fires that incinerated a swath of Los Angeles revealed the shortcomings of the current climate-obsessed regime. To be sure, Trump’s claim that water policies created the conflagration is largely false, but the lack of attention to water delivery and forest maintenance, a consistent aspect of the Brown-Newsom era, clearly contributed to the intensity of the blaze.

In 2014, California voters overwhelmingly approved a ballot measure allocating $2.7 billion to increase state water storage capacity, including the building of new reservoirs. These facilities would not only improve an aging water system neglected for decades but also capture and store precipitation that may occur in less frequent, more intense storms. Yet even government apologists concede that 10 years later, progress has been too slow, with deeply entrenched bureaucracies issuing permits only at a “glacial” pace.

Rather than building on the achievements of Pat Brown, state officials spent a quarter of a billion dollars helping environmental groups destroy dams and hydroelectric generation along the Klamath River in Northern California. While this effort may yet improve fish habitat as intended, its initial results are sobering. Most of the river’s existing fish, crustaceans, and other organisms were killed by toxic sediment as the dams were removed, and unanticipated tar-pit-like mud exposure trapped large mammals, including protected wild horses. In March 2024, fish that state biologists confidently released into the restored river perished in a mass “die-off” within two days.

These misplaced priorities are also mirrored in Los Angeles, where reservoirs were left empty, leaving water unavailable and water hydrants without pressure. Both the state and local governments have failed to sufficiently fund fire-fighting operations — except for approving lavish pensions.

The climate catastrophists may promote fires as a sign of the coming apocalypse, but still consistently oppose effective fire management, as the Little Hoover Commission found as far back as 2018, discouraging such things as controlled burns and brush clearance. Policies of controlled burns, practiced by Native Americans and in areas like Western Australia, have been largely ignored.

Even as he rails against “misinformation,” Newsom blamed the recent Los Angeles fires, as he has regarding earlier blazes, on climate change. This claim has been widely debunked by scientists like Steve Koonin, Roger Pielke, and the U.S. Geological Service. Undaunted, Newsom’s neat solution appears to be to sue the oil companies for fires made far worse by Newsom’s own policies.

The greening of decline

Charred landscapes and burned houses reflect one legacy of California’s progressive obsessions. The impact of taxes and climate regulations on the overall economy has been more widespread, particularly for minorities and working- and middle-class households, who were once the focus of traditional liberalism.

This shift has been bolstered by the ascendancy of public employee unions and the remarkable growth of the state bureaucracy. California, under Pat Brown, largely avoided public employee unions, but Jerry Brown and other governors reversed this policy. Since 2022, even with budget shortfalls, California has among the highest rates of government sector growth in the country. Today, they are widely seen as a dominant force in Sacramento. Particularly powerful has been the 310,000-member California Teachers Association. Their numbers have continued to swell, even amid budget shortfalls, at a faster rate than private-sector employment.

Public employees, or their union representatives, constitute a powerful part of California’s emerging class hierarchy. Increasingly, their livelihoods are tied to an agenda of ever more regulation and taxes. Public workers, of course, also share these costs, but more regulation also engenders more jobs for the bureaucracy.

Ultimately, California, the birthplace of youth culture, is getting old — with some places more resembling Hawaii than the entrepreneurial powerhouse of the past.

Unfortunately, the vast majority of Californians, particularly the working class, do not enjoy such benefits. In assessing the impacts of climate policies, environmental and civil rights attorney Jennifer Hernandez has dubbed these policies “the Green Jim Crow,” linking the state’s climate regulatory effort to the impoverishment of millions. California has the highest energy prices in the continental U.S., double the national average, which has exacerbated “energy poverty,” particularly among the poor and those in the less temperate interior.

In 2023, Chapman University researcher Bheki Mahalo found that the tech and information sector accounted for close to two-thirds of state GDP, compared to 8.5% in 1985. Virtually every sector associated with blue-collar employment — manufacturing, construction, transportation, and agriculture — has declined while most others have stagnated.

Consider California’s once-vibrant fossil fuel industry. The state’s last major oil firm, Chevron, recently moved to Houston. In 1996, California imported less than 10% of its crude oil from foreign sources. In 2023, foreign suppliers such as Iraq and Saudi Arabia accounted for over 60% of the state’s supplies. This continued shuttering of the state’s fossil fuel industry will cost California as many as 300,000 generally high-paying jobs, roughly half held by minorities, and will devastate, in particular, the San Joaquin Valley, where 40,000 jobs depend on the oil industry.

Other blue-collar industries — construction, manufacturing, logistics, and agriculture — are also suffering under California’s climate policies. Over the past decade, it has fallen into the bottom half of states in manufacturing sector employment, ranking 44th in 2023. Its industrial new job creation has paled in comparison to gains from competitors such as Nevada, Kentucky, Michigan, and Florida. Even without adjusting for costs, no California metro area ranks in the U.S. top 10 in terms of well-paying blue-collar jobs. But four — Ventura, Los Angeles, San Jose, and San Diego — sit among the bottom 10.

But not all the damage has been limited to “the carbon economy.” Progressive climate, labor, and tax policies have chased a broad range of companies out of the state, including an array of leading companies tied to professional services and engineering: Jacobs Engineering, Parsons, Bechtel, Toyota, Mitsubishi, Nissan, Charles Schwab, and McKesson. Even Hollywood is hemorrhaging jobs, and recently, In-N-Out Burger — the state’s widely beloved fast food chain — announced it is planning a move to Tennessee. California is increasingly losing ground both in tech and high-end business services to sprawling, low-density metro areas like Austin, Nashville, Orlando, Charlotte, Salt Lake City, and Raleigh.

California, once the land of opportunity, is the single worst state in the nation when it comes to creating jobs that pay above average, while it is at the top of the heap in creating below-average and low-paying jobs. The state hemorrhaged 1.6 million above-average-paying jobs in the past decade, more than twice as many as any other state. Since 2008, the state has created five times as many low-wage jobs as high-wage jobs. In the past three years, the situation worsened, with 78.1% of all jobs added in California from lower-than-average-paying industries versus 61% for the nation as a whole.

The only sector that has seen big growth in higher-wage jobs has been the government, which is funded by tax receipts from the struggling private sector. Public sector employment is growing at about the same pace as jobs overall in California, but over the decade at twice the national pace. The average annual pay for those public sector government jobs is now almost double that of private sector jobs.

The housing crisis: Middle-class kill shot

The lack of well-paying jobs meshes poorly with high living costs, notably in terms of housing. Here again, climate politics play a critical role in driving high housing prices in California. In the late 1960s, the value of the typical California home was more than four times the average household’s income. Today, it’s worth more than 11 times. The median California home is priced nearly 2.5 times higher than the median national home, according to 2022 census data.

A key driver of this price hike is climate policy restraints on suburban development and single-family housing, supposedly to cut residential emissions. These restrictions push putting new housing close to transit in a state where barely 3% of employees use it to get to work, according to the American Community Survey. Perhaps more to the point, these policies are not what most Californians want. One recent Public Policy Institute of California survey has found that 70% of Californians prefer single-family residences, according to a poll by former Obama campaign pollster David Binder, and oppose legislation, written by state Senator Scott Wiener (D), that banned single-family zoning in much of the state.

The state has tried to sell its density dream as a means to boost production as well as lower prices. It has not worked out. From 2010 to 2023, California’s housing stock rose by just 7.9%, lower than the national increase of 10.3% and well below housing growth in Arizona (13.8%), Nevada (14.7%), Texas (24%), and Florida (16.2%). These states are also the primary beneficiaries of California’s out-migration. An unusually large pool of affluent households is “stuck” and bids up prices in urban rental markets.

Today, home ownership is becoming rarer among California residents. The state now has the nation’s second-lowest home ownership rate, at 55.9%, slightly above New York (55.4%). High prices impact young people, particularly on the home ownership rate.

Home ownership for Californians under 35 has fallen by more than half since 1980 and is plummeting even among people in their 40s and 50s. These initiatives particularly impact minorities. Based on census data analyzed by demographer Wendell Cox, the state’s African-American home ownership rate is 35.5% — well below the national rate of 44% — and the state’s Latino home ownership rate ranked 41st nationwide.

From surfboard to walker?

If you think of California’s wealth-creation machine as a conveyor belt, continually providing generations with a stake in society through their homes, that belt has now stalled. Reduced economic opportunity and lack of affordable housing have created something once thought impossible — population growth well below the national average. In virtually every survey exploring why residents are leaving the state, housing costs are at the top of the list.

Increasingly, California’s demographics resemble the pattern of out-migration long associated with Northeastern and Midwestern states. Since 2000, more than 4 million net domestic migrants, a population about the same as the Seattle metropolitan area, have moved to other parts of the nation from California. Since 2020, the pace has picked up, with almost 1.5 million domestic migrants in just four years.

Many leaving the state are in their 30s and 40s, precisely the group that tends to buy houses and start businesses. In 2022, California lost over 200,000 net migrants older than 25, the bulk of whom had either four-year or associate degrees. The groups showing the biggest tendency to leave, according to IRS numbers, are those in their late 30s to late 50s, which includes people who tend to have families.

At the same time, international migration, long a source of demographic vitality, has lagged behind other key states, notably Texas. As the Brookings Institution has noted, from 2010 to 2018, the foreign-born population of Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, Austin, Columbus, Charlotte, Nashville, and Orlando increased by more than 20%, while San Francisco’s foreign-born population grew only 11% and New York’s by 5%.

The state retains by far the nation’s largest foreign-born population, but even the massive movement allowed under Biden’s open-border policy since 2021 failed to reverse population declines in big California cities. With the border now effectively closed, this last source of population growth is likely to decline.

By losing immigrants and younger people, the state is effectively consuming its “seed corn.” The state’s total fertility rate, long above the national average, is now the nation’s 10th lowest and falling faster than the national average and than its key competitors. Los Angeles and San Francisco rank last and second to last in birth rates among the 53 major U.S. metropolitan areas. In California, only the Riverside and San Bernardino metroplex exceeds the national average for births among women between ages 15 and 50, according to the American Community Survey.

Ultimately, California, the birthplace of youth culture, is getting old — with some places more resembling Hawaii than the entrepreneurial powerhouse of the past. From 2010 to 2018, California aged 50% more rapidly than the rest of the country, according to the American Community Survey. As of 2022, 21% — or 8.3 million people — were over the age of 60 in California, and according to the California Department of Aging, this population is expected to grow by 40% in the next 10 years.By 2036, seniors will be a larger share of the population than kids under the age of 18. California is gradually ditching the surfboard and adopting the walker.

Needed: A new California agenda

Newsom’s response to the state’s decline, rather than a call for major reform, has been for “Trump-proofing” the state, spending tens of millions on lawsuits. Such gestures do not address how California can maintain its status as the epicenter of “the new economy” and address the vast divides between the elite and highly educated and the vast mass of our residents.

Rather than fight the president at every turn, California can find ways to take advantage of the new regime. After all, hanging on to the climate agenda is doing very little good for Californians or the planet. California has reduced its emissions since 2006 at roughly the same rate as the rest of the country. The fires have largely erased even these gains, as does the fact that when people or companies flee the state, their carbon signature tends to increase.

Oddly, Trump could force needed policy changes in order to bring in federal help — something Newsom has already done in regard to water policy. The notion that California has a better model — the rationale for the Newsom-led “resistance” — does not sell in the rest of the country, much less at the White House. In a national 2024 survey conducted for the Los Angeles Times, only 15% of respondents felt that California is a model other states should copy; 39% said the state was not a model and should not be emulated; 87% said the state was too expensive; and 77% would not consider moving to California.

Yet for all its problems, California is far from hopeless, and its promise is not extinguished. It remains uniquely gifted in terms of climate, innovation, and entrepreneurial verve. Sitting at the juncture of Asia, Latin America, and North America, it can once again become, as Kevin Starr noted, America’s “final frontier: of geography and of expectation.”

Editor’s note: This article was originally published by RealClearInvestigations and made available via RealClearWire.

Drought restrictions will almost certainly be back in a state where decades-long dry periods are the norm. Is anyone preparing?

Drought restrictions will almost certainly be back in a state where decades-long dry periods are the norm. Is anyone preparing? California hasn't built a new dam in four decades, and more than 80 percent of the state's winter rainwater is annually wasted.

California hasn't built a new dam in four decades, and more than 80 percent of the state's winter rainwater is annually wasted.

California lawmakers approved a five-year extension of the state's largest power plant as residents brace for weekend blackouts.

California lawmakers approved a five-year extension of the state's largest power plant as residents brace for weekend blackouts. Environmental hazards could be diminished by proper mitigation, turning plant waste products into lucrative commodities.

Environmental hazards could be diminished by proper mitigation, turning plant waste products into lucrative commodities.

Harrison Ford Is Complete Hypocrite About "Climate Change"