James Talarico's false gospel of consent

In his 1539 tour de force "The Institutes of the Christian Religion," John Calvin wrote:

And it becomes us to remember that Satan has his miracles, which, although they are tricks rather than true wonders, are still such as to delude the ignorant and unwary.

That warning feels timely when Scripture is invoked not to illuminate truth, but to sanctify the spirit of the age.

American Christians increasingly encounter Scripture filtered through political frameworks that recast its central doctrines in therapeutic or ideological terms.

Pro-choice Jesus?

Texas Democrat state Rep. James Talarico recently argued on Joe Rogan’s podcast that the Bible affirms a woman’s right to abortion. His reasoning centers on the story of Mary in Luke 1. According to Talarico, before the Incarnation, God sought Mary’s consent. From that, he concludes that “creation has to be done with consent” and that forcing a woman to carry a child is inconsistent with the life and ministry of Jesus.

Specifically, Talarico asserted that the Bible — the inerrant and infallible word of God and the most important moral road map ever given to humanity — supports a woman’s right to kill her unborn child. On Rogan’s show, he grounded that claim in the story of Mary:

Before God comes over Mary, and we have the Incarnation, God asks for Mary’s consent. … The angel comes down and asks Mary if this is something she wants to do, and she says … let it be done. … To me that is an affirmation … that creation has to be done with consent. You cannot force someone to create. … It has to be done with freedom. … And to me that is absolutely consistent with the ministry and life and death of Jesus.

This is a remarkable interpretation, because it is not what Luke says.

Assent vs. consent

In Luke 1:26-38, Gabriel does not ask Mary a question or seek her permission. Across major English translations and historic Christian traditions alike, the text records no request for consent — only a declaration of what God will do. Gabriel announces: “Fear not, Mary: for thou hast found favour with God. And, behold, thou shalt conceive in thy womb, and bring forth a son, and shalt call his name Jesus.”

The only question in the entire exchange is Mary’s — after she is told what will happen: “How shall this be, seeing I know not a man?” Gabriel replies by pointing to God’s power: “For with God nothing shall be impossible.” Mary then responds, “Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it unto me according to thy word.”

That is assent — humble submission to God’s revealed will — not consent in the modern, contractual sense. Assent is agreement; consent is permission. Mary was not asked for permission. She freely expressed obedience to what had been declared.

Throughout Scripture, when God acts to fulfill His redemptive purposes, He does not canvass human preferences. In Job 1, when Satan is permitted to test Job’s faith, God does not first consult Job. On the road to Damascus, the risen Christ does not ask Saul whether he is open to a career change. He confronts him, humbles him, and commissions him.

God’s sovereignty is not contingent upon human authorization.

Projecting politics

To read Luke 1 as a divine appeal for permission is to project modern autonomy backward into an ancient text. It is eisegesis dressed up as compassion. It reshapes the Incarnation — the central miracle of Christianity — into an endorsement of procedural self-determination. That move says more about contemporary politics than it does about first-century Judea.

Talarico is right about one thing: The conception of a child is a holy matter. But holiness in Scripture is not synonymous with personal autonomy. Holiness is what belongs to God and reflects His purposes.

Christians have historically distinguished between God’s unique act of creation ex nihilo and human procreation within creation. A child conceived by a man and a woman bears the image of God. That image is not a private possession to be revoked; it is a gift.

To ground abortion rights in the Annunciation is therefore doubly strained. First, because the text does not describe a request for consent. Second, because the child at the center of the story is not an abstraction but the incarnate Son of God — the clearest possible affirmation that life in the womb is not disposable.

RELATED: Is Trump targeting Talarico? Colbert’s lie exposed

God's justice, not class warfare

Talarico also invokes Mary’s Magnificat — her song in Luke 1:46-55 — emphasizing its language about scattering the proud and sending the rich away empty. This has long been read in some quarters as evidence that Jesus’ mission was primarily political: a revolutionary program of economic leveling.

Yet the Gospels resist that reduction. Jesus speaks often about wealth, but His warnings concern idolatry of the heart, not the mere possession of resources. In parable after parable, wealthy figures appear without blanket condemnation. The dividing line is not income but allegiance — whether one serves God or mammon.

The Magnificat celebrates God’s justice, not class warfare. It announces the reversal of human pride before divine authority. To turn it into a manifesto for contemporary policy debates is to flatten its theological depth.

There is a broader concern here than one legislator or one podcast appearance.

American Christians increasingly encounter Scripture filtered through political frameworks that recast its central doctrines in therapeutic or ideological terms. Words like “justice,” “freedom,” and “consent” are imported into passages that were written to reveal God’s character and His plan of redemption, not to ratify modern slogans.

When believers lack grounding in the text itself, such reinterpretations can sound persuasive. They appeal to familiar moral intuitions and baptize contemporary assumptions with biblical language.

But the authority of Scripture rests not in its adaptability to the spirit of the age, but in its resistance to it. When politics begins rewriting the Annunciation, Christians should recognize the warning signs.

False prophets

Jesus Himself warned of such distortions: “And then if any man shall say to you, Lo, here is Christ; or, lo, he is there; believe him not: For false Christs and false prophets shall rise, and shall show signs and wonders to seduce, if it were possible, even the elect” (Mark 13:21-22).

The danger is not always open hostility to the faith. It is the subtle refashioning of Christ in our own image.

The Annunciation is not a lesson in personal sovereignty. It is a revelation of divine initiative. God acts; Mary receives. Her greatness lies not in negotiating terms, but in faithful obedience: “Behold the handmaid of the Lord.”

That posture — humility before God’s word — is increasingly countercultural. It does not flatter our sense of autonomy. It does not place human choice at the center of the story.

Yet Christianity has always insisted that salvation begins with surrender, not self-assertion.

To know the Bible

James Talarico may fade from public attention. The temptation to refashion Scripture in the image of prevailing politics will not. The greater danger is not that politicians cite the Bible inaccurately. It is that Christians cease to know it well enough to recognize the difference.

A nation unfamiliar with its founding documents is vulnerable to distortion. A church unfamiliar with its Scriptures is vulnerable to something worse.

The more believers read, wrestle with, and internalize the Bible, the less susceptible they will be to interpretations that trade theological substance for cultural applause.

The Incarnation does not endorse a “gospel of consent.” It proclaims a sovereign God who enters history for the salvation of His people — and a young woman who responds not with negotiation, but with trust.

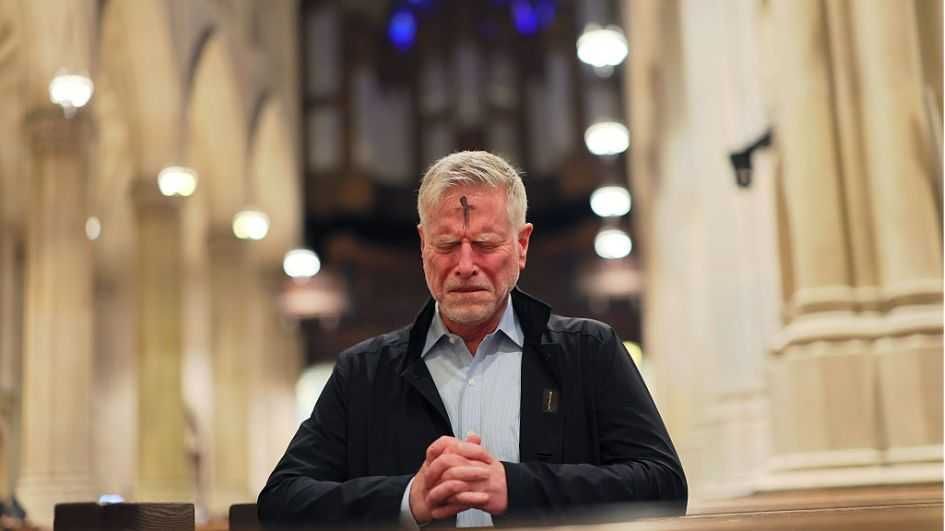

Sydney Morning Herald/Antonio Ribiero/Getty Images

Sydney Morning Herald/Antonio Ribiero/Getty Images

Photo by Bloomberg/Getty Images

Photo by Bloomberg/Getty Images

St. Francis of Assisi. Photo by: Bildagentur-online/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

St. Francis of Assisi. Photo by: Bildagentur-online/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

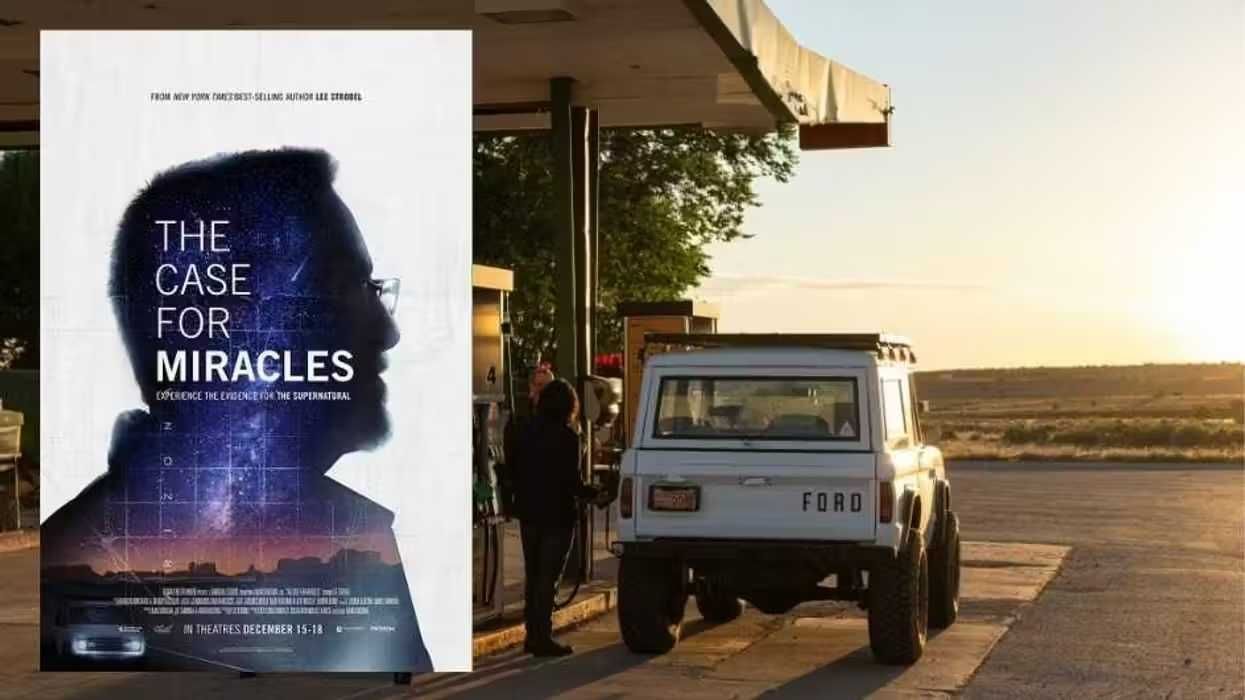

Fathom Entertainment

Fathom Entertainment People who live by the assumption that all faith is a meaningless and expedient surface posture can't speak to people who have actual faith.

People who live by the assumption that all faith is a meaningless and expedient surface posture can't speak to people who have actual faith.

Photo by Trent Nelson/The Salt Lake Tribune/Getty Images

Photo by Trent Nelson/The Salt Lake Tribune/Getty Images

Photo by David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images

Photo by David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images

'Dawson's Creek' (1997). Photo by Warner Bros./Getty Images

'Dawson's Creek' (1997). Photo by Warner Bros./Getty Images