Virtue, not power, is the true aim of politics

The great outbreak of evil in these past days stirred a memory of something I used to tell my freshman students on the first day of their introduction to politics class: Politics is about what is good.

We would read together the first sentence of Aristotle’s “Nicomachean Ethics”— an unrivaled introduction to politics:

Every art and every inquiry, and likewise every action and choice, seems to aim at some good, and hence it has been beautifully said that the good is that at which all things aim.

Aristotle goes on quickly to observe in his usual empirical way that many goods exist along with many arts developed to achieve the different goods. The medical art aims at the good of health. The art of shipbuilding aims at building good ships. The military art aims at victory in war. The art of managing the household, which the Greeks called economics, aims at the good of wealth.

Virtue is the end or aim of political life.

Some arts are subordinated to other arts, because the good at which the art aims is subordinate to a larger good, the way the art of the cavalryman is subordinate to the art of the general.

Aristotle then introduces the subject of politics with a great hypothesis: If there exists some good, some end, that we seek for its own sake, and we seek all the rest for the sake of or on account of this one good — if, in other words, we don’t choose everything for the sake of something else, which would make all of our desires empty and pointless — this would be the good itself, in fact the highest good.

He asks: Would not an awareness of this highest good have great weight in a man’s life? Wouldn’t the art of attaining that good be the sovereign or master art encompassing all the ends or goods of the other arts? And isn’t this what we call the art of politics?

The good that the art of politics aims at, he says, is “the human good.” What name do people give to the human good that encompasses all others and lacks nothing? The Greek word, Aristotle says, is eudaimonia, which we usually translate as “happiness” in English. The art of politics is the art of happiness. But it gets even better.

The art of politics is a practical art. It aims not just at knowing what happiness is but at being happy. Thinking happiness through, Aristotle finds that it does not have primarily to do with the body. It is an activity of the soul in accordance with virtue — in fact, in accordance with complete virtue. You can’t be a happy man without being a good or virtuous man. And in this sense, virtue is the end or aim of political life.

Aristotle goes on to distinguish between virtues of character and virtues of intellect, or what we usually call moral and intellectual virtues. He argues that the specific virtue or excellence of the statesman — the political man par excellence — is the intellectual virtue of practical wisdom, what he would call “phronesis.” Phronesis is the only intellectual virtue that is inseparable from moral virtue. According to Aristotle, a man cannot possess phronesis without possessing all the moral virtues actively and in their fullness. He is a man in full.

I would tell students that to make progress in their study of politics — this practical art — they would have to make progress in virtue; they would have to make progress toward the human good; they would have to make progress toward happiness. This is what our semester would be about.

Happiness and politics go together?

If I were lucky, at least one hesitatingly confident realist among the students — they were still too young to be cynics — would be brave enough on this first day of class to raise a hand and say deferentially and politely something like: “What! Have you read a newspaper lately?” (They had newspapers back then.) “Every page is filled with violence, crime, corruption, and somebody grasping for power! To call someone a politician is an insult.”

And so the semester would be off and running.

I would admit that though Aristotle in his “Politics” defines man as a “political animal” because man is a “rational animal” — an animal possessing logos, or reason — he makes an empirical observation at the end of his “Ethics” that will be familiar to anyone who has read a newspaper: Rational creatures though they are, men sometimes do not listen to reason and are carried away by their passions.

Aristotle would agree with Alexander Hamilton, or rather Hamilton agreed with Aristotle, when he wrote in Federalist 15:

"Why has government been instituted at all? Because the passions of men will not conform to the dictates of reason and justice, without constraint.” And with James Madison’s even more famous saying, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary."

In addition, working on our non-angelic human fallibility and culpability, bad education causes us to make mistakes about what is good. For these reasons, Aristotle argues that both education and coercion are central to the art of politics and, alas, that practicing the art of politics is not a leisurely activity. It is the burdensome art of inducing others to do what they ought to do for their own good and happiness, even when they don’t want to.

These days, our children learn in school and online that it is good to shoplift or try to change themselves from a boy to a girl or from a girl to a boy. A shockingly large percentage of them have learned that it is good to kill those who disagree with you.

From his first day in office in 2021, Joe Biden — our then-educator in chief — made it the central point of American politics that being trans was being good and questioning the goodness of being trans was evil. He thrust this bad education into the face of his country — marching trans heroes before the cameras to model the “goodness” that all Americans should admire and publicly praise if they wanted to avoid ostracism, public shaming and canceling, expulsion from school, losing their jobs, being put in jail, or being murdered in cold blood.

Politics requires goodness

Knowing what is good is not easy. A man in ancient Athens with the greatest reputation for wisdom knew only that he did not know what was good. To have what was good, to be good, was so crucial to Socrates — the one thing needful — that it made no sense to do anything else with his life than to try to find out what it was.

RELATED: We all knew political murder was coming home

But we do not need to be philosophers to know that boys cannot become girls, that biological males should not be competing against biological females in sports or sharing their bathrooms, and that killing those who disagree with us is evil. Glenn Ellmers, Salvatori Research Fellow at the Claremont Institute and an old friend, published a short essay on the urgent need, in this increasingly deranged world, to hold on to our common sense.

Machiavelli — the infamous teacher of “realist” politics — seeing unflinchingly what we all could read in the newspaper, taught that in a world where so many are so bad, it is merely common sense that it is necessary for those who would succeed in the art of politics to enter into evil. I would suggest an alternative lesson to students, one that I think is in the spirit of Aristotle: In a world where so many are so bad, it is merely common sense that it is necessary for the good to be great.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published at the American Mind.

Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images

Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images Photo by Harold M. Lambert/Getty Images

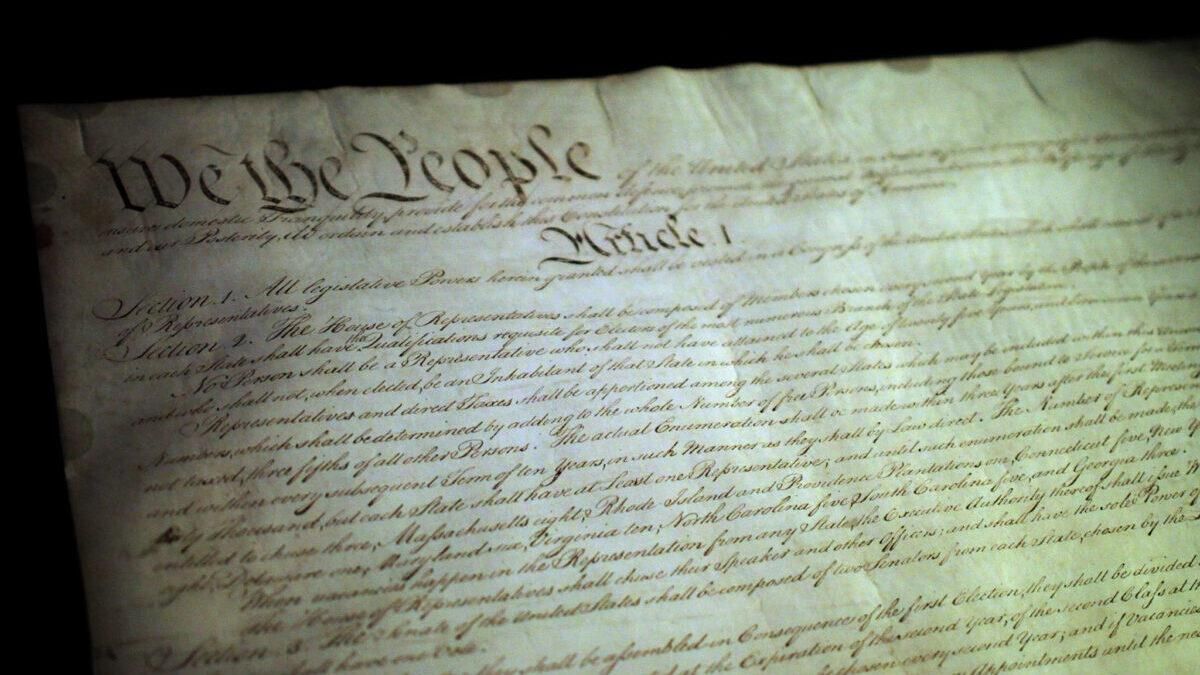

Photo by Harold M. Lambert/Getty Images In four years, Biden used his Article 2, Section 2 powers more than 8,064 times.

In four years, Biden used his Article 2, Section 2 powers more than 8,064 times. If you think the only explanation for a 9-0 Supreme Court decision in Trump's favor is because Sonia Sotomayor is a MAGA extremist, you might need to touch grass.

If you think the only explanation for a 9-0 Supreme Court decision in Trump's favor is because Sonia Sotomayor is a MAGA extremist, you might need to touch grass. Direct democracy not only represents a threat to freedom, but it is a political order that rejects hierarchies both natural and spiritual.

Direct democracy not only represents a threat to freedom, but it is a political order that rejects hierarchies both natural and spiritual. Destroying trust in the court opens the floodgates for government abuse and destabilizes the nation in unprecedented ways.

Destroying trust in the court opens the floodgates for government abuse and destabilizes the nation in unprecedented ways.

Chuck DeVore's historical fiction book 'Crisis of the House Never United: A Novel of Early America' demonstrates not only why procedure and patience matter, but also the genius of the U.S. Constitution.

Chuck DeVore's historical fiction book 'Crisis of the House Never United: A Novel of Early America' demonstrates not only why procedure and patience matter, but also the genius of the U.S. Constitution. The left's push for a popular vote for the presidency directly undermines the electoral system established by our Constitution.

The left's push for a popular vote for the presidency directly undermines the electoral system established by our Constitution.