Without George Washington, America Wouldn’t Have A 250th Birthday

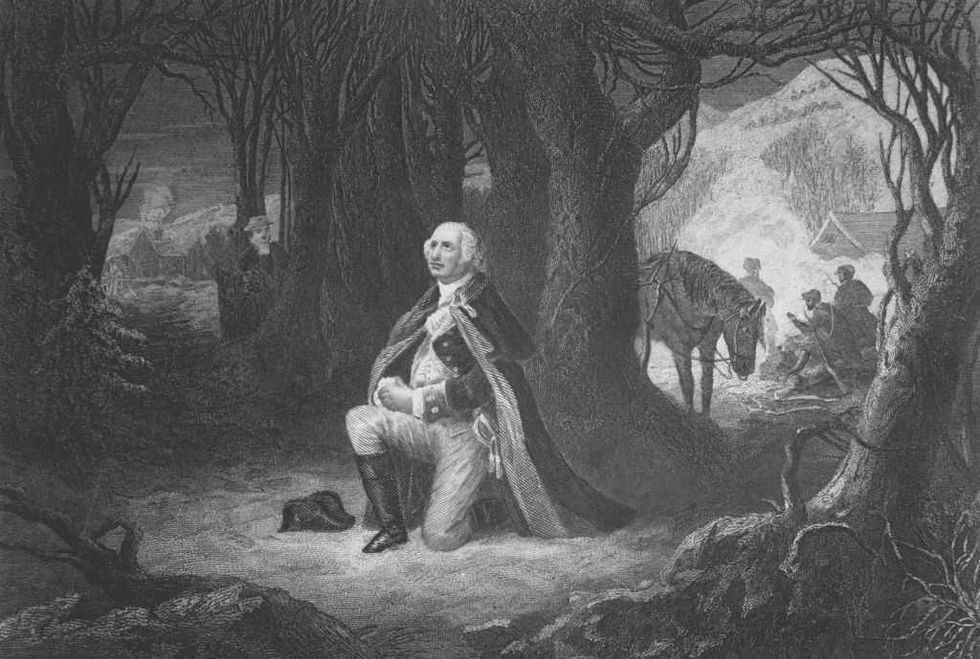

No one looms larger in the story of our nation's struggle for independence than George Washington, who today seems almost mythical.

No one looms larger in the story of our nation's struggle for independence than George Washington, who today seems almost mythical.Earlier this week, Secretary of War Pete Hegseth announced that he would be overhauling yet another aspect of the military: the Chaplain Corps.

On Tuesday, Hegseth explained a directive that will effectively overhaul the United States Chaplain Corps, "the spiritual and moral backbone of our nation's forces" that, for hundreds of years, "ministered" to the "souls" of American servicemen and women, as he explained in the video.

'In an atmosphere of political correctness and secular humanism, chaplains have been minimized, viewed by many as therapists instead of ministers.'

Hegseth recounted the long history of the Chaplain Corps, which dates back to 1775, when George Washington himself established it. The "weakening" of this important institution has become "a real problem for our nation's military," Hegseth said.

"Sadly, as part of the ongoing war on warriors, in recent decades its role has been degraded," Hegseth said in the video. "In an atmosphere of political correctness and secular humanism, chaplains have been minimized, viewed by many as therapists instead of ministers. Faith and virtue were traded for self-help and self-care."

As evidence of the New Age influence in the military, Hegseth referred to the United States Army's Spiritual Fitness Guide, which mentions "God" only once and "virtue" not at all, even as 82% of the military identify as "religious."

Hegseth ordered the elimination of this "unacceptable and unserious" Spiritual Fitness Guide and the simplification of the Faith and Belief Coding System, an "overly complex" classification system of over 200 different beliefs.

The Faith and Belief Code was apparently expanded in March 2017. The expansion went into more detailed distinctions among Protestant denominations, and it included alternate belief systems like "Magick and Spiritualist," "Wicca," "Pagan," "New Age Churches," "Humanist," and "Heathen."

Hegseth promised more changes in the near future, saying that there will be a "top-down cultural shift" in the military that puts "spiritual well-being on the same footing as mental and physical health."

"We are going to make the Chaplain Corps great again," he posted on X.

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!

There was a time when Thanksgiving pointed toward something higher than stampedes for electronics or a long weekend of football. At its root, Thanksgiving was a public reminder that faith, family, and country are inseparable — and that a free people must recognize the source of their blessings.

Long before Congress fixed the holiday to the end of November, colonies and early states observed floating days of thanksgiving, prayer, and fasting. These were civic acts as much as religious ones: moments when communities asked God to protect them from calamity and guide their families and their nation.

The Continental Congress issued the first national Thanksgiving proclamation in 1777, drafted by Samuel Adams. The delegates called on Americans to acknowledge God’s providence “with Gratitude” and to implore “such farther Blessings as they stand in Need of.”

Twelve years later, President George Washington proclaimed the first federal day of thanksgiving under the Constitution. He asked citizens to gather in public and private worship, to seek forgiveness for “national and other transgressions,” and to pray for the growth of “true religion and virtue.”

Our problems — social, fiscal, and moral — are immense. But they are not greater than the God our ancestors trusted.

Other presidents followed suit. During rising tensions with France in 1798, John Adams declared a national day of “solemn humiliation, fasting, and prayer,” arguing that only a virtuous people could sustain liberty. The next year he called for another day of thanksgiving, urging citizens to set aside work, confess national sins, and recommit themselves to God.

For generations, this was the American understanding: national strength flowed from moral character, and moral character flowed from religious conviction.

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln — responding to years of lobbying by Sarah Josepha Hale — established the last Thursday in November as a permanent national Thanksgiving. Hale saw the holiday as a unifying civic ritual that strengthened families and reminded Americans of their shared heritage.

Calvin Coolidge echoed this tradition in 1924, observing that Thanksgiving revealed “the spiritual strength of the nation.” Even as technology transformed daily life, he insisted that the meaning of the day remain unchanged.

But as the country drifted from an agricultural rhythm and from public expressions of faith, the holiday’s original purpose faded. The deeper meaning — gratitude, repentance, unity — gave way to distraction.

Today, America marks Thanksgiving with a national character far removed from the one our forebears envisioned. The founders believed public acknowledgment of God’s authority anchored liberty. Modern institutions increasingly treat religious conviction as an obstacle.

Court rulings have redefined marriage, narrowed the space for religious conscience, and removed long-standing religious symbols from public grounds. Citizens have been fined, penalized, or jailed for refusing to violate their beliefs. The very freedoms early Americans prayed to preserve are now treated as negotiable.

At the same time, other pillars of national life — family stability, civic order, border security, self-government — erode under cultural and political pressure. As faith recedes, government fills the void. The founders warned that a people who lose their internal moral compass invite external control.

Former House Speaker Robert Winthrop (Whig-Mass.) put it plainly in 1849: A society will be governed “either by the Word of God or by the strong arm of man.”

The collapse of religious conviction in much of Europe created a vacuum quickly filled by ideologies hostile to Western values. America resisted this trend longer, but the rising influence of secularism and identity ideology pushes our society toward the same drift: a nation less confident in its heritage, less united by a common purpose.

Ronald Reagan saw the warning signs decades ago. In his 1989 farewell, he lamented that younger generations were no longer taught to love their country or understand why the Pilgrims came here. Patriotism, once absorbed through family, school, and culture, had been replaced by fashionable cynicism.

Thanksgiving offers the antidote Reagan urged: a return to gratitude, history, and shared purpose.

RELATED: Why we need God’s blessing more than ever

Thanksgiving was meant to be the clearest expression of a nation united by faith, family, and patriotism. It rooted liberty in gratitude and gratitude in God’s providence.

Reagan captured that spirit in 1986, writing that Thanksgiving “underscores our unshakable belief in God as the foundation of our Nation.” That conviction made possible the prosperity and freedom Americans inherited.

Today’s constitutional conservatives must lead in restoring that heritage — not by nostalgia, but by example. Families who teach gratitude, faith, and national purpose build the civic strength the founders believed essential.

Thanksgiving calls each of us to humility: to recognize that national renewal begins with personal renewal. Our problems — social, fiscal, and moral — are immense. But they are not greater than the God our ancestors trusted.

That confidence is the heart of Thanksgiving. It is why the Pilgrims prayed, why Congress proclaimed days of fasting and praise, why Lincoln unified the holiday, and why generations of Americans pause each November to give thanks.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared at Conservative Review in 2015.

Thanksgiving is an annual reminder of our nation’s Christian roots and our godly heritage. Although Virginia proclaims that the first Thanksgiving was in Jamestown in 1619 — not in Plymouth in 1621 — the Plymouth one became the prototype of our annual celebrations.

George Washington was the first president under the Constitution to declare a national day of thanksgiving, and President Lincoln was the first to declare Thanksgiving an annual holiday.

'It is the indispensable Duty of all Men to adore the superintending Providence of Almighty God; to acknowledge with Gratitude their Obligation to him for Benefits received, and to implore such further Blessings as they stand in Need of ...'

However, Samuel Adams, with the help of two other continental congressmen, was the first to declare a National Day of Thanksgiving for America as an independent nation.

The time was the fall of 1777. Overall, it seemed that things were not going well for the United States. Americans lost the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, which Dr. Peter Lillback notes was our "first 9/11."

George Washington saw that the Brandywine defeat meant the impending fall of Philadelphia, our nation’s capital at the time, into the hands of the British.

So Congress had to flee westward, first to Lancaster and then to York, Pennsylvania. Washington and his troops had to flee westward also. They ended up in a place called Valley Forge. The worst was yet to come with the brutal winter there.

Meanwhile, on October 7, 1777, there was a victory at Saratoga, New York. Samuel Adams of Boston, a key leader in American independence, saw that we as a nation could rejoice in this act of divine Providence. So — with the help of fellow Continental Congressmen Rev. John Witherspoon of New Jersey and Richard Henry Lee of Virginia — Samuel Adams wrote our country’s first thanksgiving declaration as an independent nation.

This is what they wrote in that First National Thanksgiving Proclamation, November 1, 1777: "It is the indispensable Duty of all Men to adore the superintending Providence of Almighty God; to acknowledge with Gratitude their Obligation to him for Benefits received, and to implore such further Blessings as they stand in Need of.”

As humans, as Christians, we should be grateful. They continue, “And it having pleased him in his abundant Mercy, not only to continue to us the innumerable Bounties of his common Providence; but also to smile upon us in the Prosecution of a just and necessary War, for the Defense and Establishment of our unalienable Rights and Liberties; particularly in that he hath been pleased, in so great a Measure, to prosper the Means used for the Support of our Troops, and to crown our Arms with most signal success.”

I think it’s fair to say that Adams, Witherspoon, and Lee were looking for the good news (the Saratoga victory) in a sea of bad news (American setbacks, the latest of which was the defeat at Brandywine).

They continue: “It is therefore recommended to the legislative or executive Powers of these UNITED STATES to set apart THURSDAY, the eighteenth Day of December next, for SOLEMN THANKSGIVING and PRAISE.”

And what were the Americans to do during that day of Thanksgiving and praise? To confess “their manifold sins … that it may please GOD through the Merits of JESUS CHRIST, mercifully to forgive and blot them out of Remembrance; That it may please him graciously to afford his Blessing on the Governments of these States respectively, and prosper the public Council of the whole.”

RELATED: That we may all unite in rendering unto our Creator our sincere and humble thanks

If someone prayed like this in Congress today, people might try to drive him out of town on a rail — like the leftist members of Congress who blew a gasket when California minister Jack Hibbs prayed in the name of Jesus in Congress in early 2024.

Writing on behalf of Congress, Adams, Witherspoon, and Lee continue: “To inspire our Commanders, both by Land and Sea, and all under them, with that Wisdom and Fortitude which may render them fit Instruments, under the Providence of Almighty GOD, to secure for these United States, the greatest of all human Blessings, INDEPENDENCE and PEACE.”

They also prayed for God “to prosper the Trade and Manufactures of the People,” as well as the farmers, for success of the crops. They also asked for God’s help in the schools, which they note are “so necessary for cultivating the Principles of true Liberty, Virtue and Piety, under his nurturing Hand; and to prosper the Means of Religion, for the promotion and enlargement of that Kingdom, which consisteth ‘in Righteousness, Peace and Joy in the Holy Ghost.’”

This prayer proclamation is no namby-pamby type of prayer such as we might hear from Congress these days. These are bold proclamations of faith, showing the pro-Christian side of the founding fathers that we rarely hear about these days.

This article is adapted from an essay originally published at Jerry Newcombe's website.

The horrific assassination of Charlie Kirk in September should have united Americans. Instead, it split them even further. Conservatives watched too many of their countrymen on the left openly cheer the murder, and even weak denunciations often suggested Kirk got what he deserved.

For a time, the right rallied — praising Kirk and demanding justice. That unity didn’t last. A furious fight over Kirk’s legacy followed, and that’s worse than politics: It’s destroying the movement he built.

Charlie Kirk’s death was a monstrous crime. Let it not become the occasion for tearing the movement he led to pieces.

George Washington spent much of his Farewell Address warning the young republic about foreign entanglements. He praised American separation from Europe’s great power intrigues and warned that making any foreign state a favored nation would corrupt domestic politics. Washington foresaw factions forming around foreign loyalties and predicted patriots who raised concerns about foreign influence would be branded traitors.

His warning applies now, and the fracture cuts through conservatism itself. The United States has long allied with Israel — sharing intelligence, aid, and military cooperation. Many conservatives, especially evangelicals, treat support for Israel as near-religious obligation. Others point to practical security benefits in the Middle East. That religious devotion makes criticism of the relationship politically perilous. You can denounce Britain or Germany without being vilified. Question our alliance with Israel, and you risk immediate slurs — racist, anti-Semite, bigot.

As Washington warned, centering policy on a foreign nation invites domestic discord and foreign meddling. Qatar and other Gulf states now pour money into U.S. institutions. Diasporas like India attempt to consolidate as a power bloc. None of this would surprise Washington. It was predictable. Still, both sides chatter past his counsel — and refuse the restraint he urged.

Charlie Kirk excelled at coalition building and peacemaking. He united disparate conservatives behind Trump and MAGA. That’s why the civil war over his death is so corrosive. Conspiracy theories swirl. Former allies denounce one another in his name. Private texts between Kirk and fellow influencers have been leaked and used as weapons. The spectacle is inhuman.

The impulse to treat Kirk’s private words as scripture echoes how people now treat the Constitution — stripping context until the document becomes a cudgel for whatever program you prefer. Left and right both reduce texts to proof texts; neither seeks the actual meaning.

Kirk’s position on Israel was complicated. He loved and supported the state and saw biblical significance in its existence, yet he also held America First concerns about military commitments and complained about pressure from Zionist donors who pushed TPUSA to cancel conservatives. He sought to defuse right-wing animosity toward Israel through messaging at home and tempering excesses abroad. His views were nuanced — like most people tend to be when the shouting stops.

Instead of using the outrage over his assassination to crush the left-wing terror network behind it, too many conservatives turned inward and drew long knives. One faction hates Israel so fiercely it would harm America; another treats any deviation from absolute support as treason.

At the moment, conservatives should unify for survival, they trade blows over purity tests.

The reality is simple: Israel will remain. The conservative movement needs a coherent strategy. Religious devotion among evangelicals will persist, but it’s waning among younger Christians. Pro-Israel advocates must make a practical case to younger conservatives if they want broad support. Those who question the tie to Israel will keep growing in number.

If pro-Israel conservatives want to avoid the radicalization they fear, they must tolerate dissent within the coalition without staging public witch hunts. Those who seek to re-evaluate the relationship should keep arguments factual and pragmatic. Washington’s cautions about favored nations and about letting hatred sabotage the country remain relevant.

RELATED: Christians are refusing to compromise — and it’s terrifying all the right people

We saw, after Kirk’s killing, how large segments of the left revealed a murderous contempt for conservatives. That truth cannot be unseen. But within conservatism, the critical question is whether your rival on the right is an opponent to debate or an enemy to be excised. Zionist or skeptic, neither camp is calling for your child to be shot. That low bar — refusing to wish literal violence on fellow citizens — must hold if conservatives hope to form a durable coalition.

This is not an appeal to centrism. I have my views and have argued them plainly. But Kirk wanted a movement that could hold together. He worked to build a broad tent. The conservative civil war must end because the stakes are too high.

If conservatives continue sniping through Kirk’s memory, they will squander their political capital and invite worse divisions. Washington warned us what happens when foreign loyalties and religious fervor distort public life; he warned that factional hatred breaks nations. Conservatives ought to remember that now — not to moderate principle for its own sake, but to preserve the only structure that allows principle to matter: a functioning political majority.

Charlie Kirk’s death was a monstrous crime. Let it not become the occasion for tearing the movement he led to pieces. The left must be opposed forcefully and without mercy in politics, but infighting on the right hands them victory. Put down the knives. Honor Kirk by building the coalition he believed in — or watch the movement dissolve into impotence.

The United States faces an existential threat from the accelerating military power of communist China — a buildup fueled by decades of massive economic expansion. If America intends to counter Beijing’s ambitions, it must grow faster, leaner, and more efficient. Economic strength is national security.

The ongoing government shutdown may not be popular, but it gives President Trump a rare opportunity to make good on his campaign pledge to drain — and redesign — “the swamp.” Streamlining the federal government isn’t just good politics. It’s a matter of survival.

A government that builds wealth rather than expands debt can out-produce China, sustain deterrence, and restore the American ideal of self-government.

George Washington ran the nation with four Cabinet departments: war, treasury, state, and the attorney general. The Department of the Interior came later, followed by the Department of Agriculture, added by Abraham Lincoln in 1862 when America was an agrarian power.

The modern Cabinet, by contrast, is a bureaucratic junkyard built more in reaction to political problems than by design. The Labor Department was carved from the Commerce Department to appease the unions. Lyndon Johnson invented the Department of Transportation. Jimmy Carter established the Department of Energy in response to the Arab oil embargo. The Department of Homeland Security and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence emerged after 9/11.

The result is a patchwork of agencies wired together with duct tape, overlap, and patronage. A government designed for crisis management has become a permanent crisis unto itself.

A return to first principles starts with a single question: How can we accelerate American productivity?

The answer: consolidate. Merge the Departments of Commerce, Labor, Agriculture, Transportation, and Energy into a Department of National Economy. One Cabinet secretary, five undersecretaries, one mission: to expand the flow of goods and services that generate national wealth.

The new department’s motto should be a straightforward question: What did your enterprise do today to increase the wealth of the United States?

Fewer bureaucracies mean fewer fiefdoms, less redundancy, and enormous cost savings. Synergy replaces stovepipes. The government’s economic engine becomes a single machine instead of six competing engines running on taxpayer fuel.

Homeland Security should be absorbed by the U.S. Coast Guard, which already functions as a paramilitary force with both military and police authority, much like Italy’s Carabinieri. Under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, DHS personnel would share discipline, training, and accountability.

FEMA would cease to be a dumping ground for political hacks. Any discrimination in disaster aid — such as punishing Trump voters — would trigger a court-martial.

The Secret Service would focus solely on protective duties, handing its financial-crime work to the FBI. The secretary of the Coast Guard would gain a seat in the Cabinet.

The Office of Director of National Intelligence should be re-established as the Office of Strategic Services, commanded by a figure in the tradition of Major General “Wild Bill” Donovan. Elements of U.S. Special Operations Command would be seconded to the new OSS, reviving its World War II lineage.

All intelligence agencies — CIA, DIA, FBI, the State Department, DEA, and the service branches — should share common foundational training. The current decline in discipline and capability at the National Intelligence University, worsened by the DEI policies of its leadership, demands urgent correction. Diversity cannot come at the expense of competence.

RELATED: Memo to Hegseth: Our military’s problem isn’t only fitness. It’s bad education.

At the Department of Justice, dissolve the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. Shift alcohol and tobacco oversight to the DEA, firearms and explosives to the U.S. Marshals.

Let the DEA also absorb the Food and Drug Administration, which would become its research and standards division.

Return the FBI to pure investigation — armed but without arrest powers. Enforcement should rest with the U.S. Marshals. Counterintelligence would move to the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency, reinforced by the Naval Criminal Investigative Service.

The IRS should be dismantled and replaced with a small agency built around a flat-tax model such as the Hall-Rabushka plan.

Move the Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response to Homeland Security. Send its Office of Climate Change and Health Equity to NOAA — or eliminate it entirely.

At the Department of Housing and Urban Development, expand the inspector general’s office tenfold and pay bonuses for rooting out fraud.

The Pentagon needs its own overhaul. Because of China’s rapid military buildup, the Air Force’s Global Strike Command should be separated from U.S. Strategic Command and report directly to the secretary of war and the president under its historic name — Strategic Air Command.

Submarines and silos are invisible; bombers are not. Deterrence depends on visibility. A line of B-1s, B-2s, B-52s, and 100 new B-21 Raider stealth bombers, all bearing the mailed-fist insignia of the old SAC, would send an unmistakable message to Beijing.

With Trump back in the White House, this moment is ripe for radical efficiency. A government that builds wealth rather than expands debt can out-produce China, sustain deterrence, and restore the American ideal of self-government.

George Washington’s government fit inside a single carriage. We won’t return to that scale — but we can rediscover that spirit. A lean, unified, strategically organized government would make wealth creation easier, limit bureaucratic overreach, and preserve the republic for the long fight ahead.

When 20-year-old loner Thomas Matthew Crooks ascended a sloped roof in Butler County, Pennsylvania, and opened fire, he unleashed a torrent of clichés. Commentators and public figures avoided the term “assassination attempt,” even if the AR-15 was trained on the head of the Republican Party’s nominee for president. Instead, they condemned “political violence.”

“There is absolutely no place for political violence in our democracy,” former President Barack Obama said. One year later, he added the word “despicable” to his condemnation of the assassin who killed Charlie Kirk. That was an upgrade from two weeks prior, when he described the shooting at Annunciation Catholic School by a transgender person as merely “unnecessary.”

Those in power are not only failing to enforce order, but also excusing and even actively promoting the conditions that undermine a peaceful, stable, and orderly regime.

Anyone fluent in post-9/11 rhetoric knows that political violence is the domain of terrorists and lone wolf ideologues, whose manifestos will soon be unearthed by federal investigators, deciphered by the high priests of our therapeutic age, and debated by partisans on cable TV.

The attempt to reduce it to the mere atomized individual, however, is a modern novelty. From the American Revolution to the Civil War, from the 1863 draft riots to the 1968 MLK riots, from the spring of Rodney King to the summer of George Floyd, the United States has a long history of people resorting to violence to achieve political ends by way of the mob.

Since the January 6 riot that followed the 2020 election, the left has persistently attempted to paint the right as particularly prone to mob action. But as the online response to the murder of Charlie Kirk demonstrates — with thousands of leftists openly celebrating the gory, public assassination of a young father — the vitriol that drives mob violence is endemic to American political discourse and a perpetual threat to order.

America’s founders understood this all too well.

In August 1786, a violent insurrection ripped through the peaceful Massachusetts countryside. After the end of the Revolutionary War, many American soldiers found themselves caught in a vise, with debt collectors on one side and a government unable to make good on back pay on the other. A disgruntled former officer in the Continental Army named Daniel Shays led a violent rebellion aimed at breaking the vise at gunpoint.

“Commotions of this sort, like snow-balls, gather strength as they roll, if there is no opposition in the way to divide and crumble them,” George Washington wrote in a letter, striking a serene tone in the face of an insurrection. James Madison was less forgiving: “In all very numerous assemblies, of whatever character composed, passion never fails to wrest the sceptre from reason. Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob,” he wrote inFederalist 55. Inspired by Shays’ Rebellion and seeking to rein in the excesses of democracy, lawmakers called for the Constitutional Convention in the summer of 1787.

If the United States Constitution was borne out of political chaos, why does the current moment strike so many as distinctly perilous? Classical political philosophy offers us a clearer answer to this question than modern psychoanalysis. The most pointed debate among philosophers throughout the centuries has centered on how to prevent mob violence and ensure that most unnatural of things: political order.

In Plato’s “Republic," the work that stands at the headwaters of the Western tradition of political philosophy, Socrates argues that the only truly just society is one in which philosophers are kings and kings are philosophers. As a rule, democracy devolves into tyranny, for mob rule inevitably breeds impulsive citizens who become focused on petty pleasures. The resulting disorder eventually becomes so unbearable that a demagogue arises, promising to restore order and peace.

The classically educated founders picked up on these ideas — mediated through Aristotle, Cicero, John Locke, and Montesquieu, among others — as they developed the structure of the new American government. The Constitution’s mixed government was explicitly designed to establish a political order that would take into consideration the sentiments and interests of the people without yielding to mob rule at the expense of order. The founders took for granted that powerful elites would necessarily be interested in upholding the regime from which they derived their authority.

History has often seen disaffected elites stoke insurrections to defenestrate a ruling class that shut them out of public life. The famous case of the Catilinarian Conspiracy in late republican Rome, in which a disgruntled aristocrat named Catiline attempted to overthrow the republic during the consulship of Cicero, serves as a striking example.

In the 21st century, we face a different phenomenon: Those in power are not only failing to enforce order, but also excusing and even actively promoting the conditions that undermine a peaceful, stable, and orderly regime.

The points of erosion are numerous. The public cheerleading of assassinations can be dismissed as noise from the rabble, but it is more difficult to ignore the numerous calls from elites for civic conflagration. Newspapers are promoting historically dubious revisionism that undermines the moral legitimacy of the Constitution. Billionaire-backed prosecutors decline to prosecute violent crime.

For years, those in power at best ignored — and at worst encouraged — mob-driven chaos in American social life, resulting in declining trust in institutions, lowered expectations for basic public order, coarsened or altogether discarded social mores, and a general sense on all sides that Western civilization is breaking down.

Without a populace capable of self-control, liberty becomes impossible.

The United States has, of course, faced more robust political violence than what we are witnessing today. But even during the Civil War — brutal by any standard — a certain civility tended to obtain between the combatants. As Abraham Lincoln noted in his second inaugural address, “Both [sides] read the same Bible and pray to the same God.” Even in the midst of a horrific war, a shared sense of ultimate things somewhat tempered the disorder and destruction — and crucially promoted a semblance of reconciliation once the war ended.

Our modern disorder runs deeper. The shattering of fundamental shared assumptions about virtually anything leaves political opponents looking less like fellow citizens to be persuaded and more like enemies to be subdued.

Charlie Kirk, despite his relative political moderation and his persistent willingness to engage in attempts at persuasion, continues to be smeared by many as a “Nazi propagandist.” The willful refusal to distinguish between mostly run-of-the-mill American conservatism and the murderous foreign ideology known as National Socialism is telling. The implication is not subtle: If you disagree with me, you are my enemy — and I am justified in cheering your murder.

Fellow citizens who persistently view their political opponents as enemies and existential threats cannot long exist in a shared political community.

“Democracy is on the ballot,” the popular refrain goes, but rarely is democracy undermined by a single election. It is instead undermined by a gradual decline in public spiritedness and private virtue, as well as the loss of social trust and good faith necessary to avoid violence.

The chief prosecutors against institutional authority are not disaffected Catalines but the ruling class itself. This arrangement may work for a while, but both political theory and common sense suggest that it is volatile and unlikely to last for long.

Political order, in general, requires a degree of virtue, public-spiritedness, and good will among the citizenry. James Madison in Federalist 55 remarks that, of all the possible permutations of government that have yet been conceived, republican government is uniquely dependent upon order and institutional legitimacy:

As there is a degree of depravity in mankind which requires a certain degree of circumspection and distrust, so there are other qualities in human nature which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence. Republican government presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form.

In short, republican government requires citizens who can govern themselves, an antidote to the passions that precede mayhem and assassination. Without a populace capable of self-control, liberty becomes impossible. Under such conditions, the releasing of restraints never liberates — it only promotes mob-like behavior.

RELATED: Radical killers turned campus heroes: How colleges idolize political violence

The disorder of Shays’ Rebellion prompted the drafting of the Constitution, initiating what has sometimes been called an “experiment in ordered liberty.” That experiment was put to the test beginning in 1791 in Western Pennsylvania. The Whiskey Rebellion reached a crisis in Bower Hill, Pennsylvania, about 50 miles south of modern-day Butler, when a mob of 600 disgruntled residents laid siege to a federal tax collector. With the blessing of the Supreme Court Chief Justice and Federalistco-author John Jay, President George Washington assembled troops to put down the rebellion.

Washington wrote in a proclamation:

I have accordingly determined [to call the militia], feeling the deepest regret for the occasion, but withal the most solemn conviction that the essential interests of the Union demand it, that the very existence of government and the fundamental principles of social order are materially involved in the issue, and that the patriotism and firmness of all good citizens are seriously called upon, as occasions may require, to aid in the effectual suppression of so fatal a spirit.

Washington left Philadelphia to march thousands of state militiamen into the rebel haven of Western Pennsylvania. The insurrectionists surrendered without firing a shot.

Our new era of political violence rolls on, with Charlie Kirk’s murder being only the latest and most prominent example. Our leaders assure us they will ride out into the field just as Washington once did. Whether they will use their presence and influence to suppress or encourage “so fatal a spirit” remains an open question.

Editor’s note: A version of this article was published originally at the American Mind.

As a woman in a leadership role of a Christian organization, I appreciate the opportunities available to me in modern America. Women can and do lead with great effectiveness in countless contexts as the Lord calls and equips women to advance His kingdom.

But let me say something that will sound scandalous to modern ears: National leadership belongs to men, and the 19th Amendment was a mistake.

Western imagination continues to swallow, without chewing, the dogma that men and women are virtually interchangeable in every respect but reproduction.

Does that shock you?

It probably does, and we have the rise of feminism and its pervasive influence on the West to thank for that.

The factory settings of the American mind are thoroughly feminist. We instinctively view women rising into roles once held exclusively by men as positive. But rarely do we pause to contemplate whether such role-swapping might actually be a factor in the sharp moral decline of the last century.

The Western imagination continues to swallow, without chewing, the dogma that men and women are virtually interchangeable in every respect but reproduction. But this is biological and biblical falsehood dressed in cultural orthodoxy. Men and women are different to the core — in body, brain, hormones, and God-given roles.

How could we possibly ignore the reality that these vast differences will have a significant impact on our institutions if we liberally swap women into governing roles?

The emotional, nurturing leanings of femininity are God-ordained. In their proper place and function, they are a strength. But when it comes to the leadership of a nation, feminine traits are an inherent weakness.

Is it time we began reconsidering this?

At the recent memorial for Charlie Kirk, masculine and feminine, government and personal were on full display. In an unforgettable moment, Erika Kirk publicly forgave her husband’s alleged murderer. This was a faithful demonstration of the gospel of God’s grace. It was right.

Not long before that, Stephen Miller, in no uncertain terms, made it abundantly clear that our enemies must be destroyed. This was a faithful demonstration of God’s justice and role of government: wielding the sword against the evildoer. It was right.

RELATED: How Erika Kirk answered the hardest question of all

For the government to absolve the doer of a wicked deed and refrain from doing justice would be evil. For an individual to forgive is right. This tension is complementary, but blurring the lines is catastrophic. While there may be the rare exception of women who understand this and are able to unflinchingly pursue justice against evildoers, the truth remains that men are intrinsically designed by their Creator for that in a way that women are not.

Seeing men and women as interchangeable in the halls of government has opened our nation up to all manner of evil. Favoring the nurturing tendencies of female leadership over the strength and forcefulness of male leadership has allowed our nation to be infiltrated by those who hate us, using the Trojan horse of misplaced compassion.

Not long ago, few questioned whether men should lead their families and their nation.

Leadership of this kind was understood as God’s assignment to men. Departure from this was the exception — not the goal. Scripture itself portrays the rule of women and children over men as a sign of divine judgment, not of blessing (Isaiah 3:12).

When 56 men signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776, no one raised an eyebrow at their failure to assemble a gender-balanced cast of signers. The signers knew they were risking their lives by writing their names on that document, and this extreme risk has always been understood to be the God-given role of men.

Voting rights, originally limited to land-owning males, followed a simple principle: Those given authority with the vote should also bear a tangible interest in society’s future. They should have skin in the game.

George Washington once warned: “It is to be lamented that more attention has not been paid to the qualifications of electors. Without property, or with little, the common interest will be disregarded or postponed to that of individuals.”

This was neither a call to oppress nor arbitrary discrimination, but it was a protective recognition of human nature. A man with land, family, and livelihood invested in the community was far less likely to cast votes carelessly than someone detached from such responsibilities.

Change came gradually. By the 1820s and 1830s, property requirements for white men were swept away in the name of “universal manhood suffrage.” By 1856, every state allowed men to vote regardless of land ownership.

This was celebrated as progress — but it marked a philosophical turning point. Authority was no longer tethered to responsibility.

The 19th century brought the women’s suffrage movement, culminating in the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. What had for millennia across the globe been seen as natural order was reframed as injustice. Strong male leadership as an ideal was abandoned in favor of sameness.

RELATED: Misogyny? Please: Our real problem is female entitlement

Instead of viewing womanhood as a high calling of influence through nurture, wisdom, and faithfulness, women began rejecting the way God has naturally wired us in order to become functionally men.

Are our families stronger for it? Is our society more stable?

Of course not. Broken homes abound. Men shrink back in passivity. Women carry burdens they were never meant to bear. Children grow up without clear models of what it means to be a man or a woman.

Feminism is destroying us, and Christians hardly want to give it a look. A Christian today would likely recoil in horror at the idea of strongly preferring a male candidate vs. a female candidate, all other conditions being equal. But this idea is thoroughly biblical.

The stats are undeniable that unmarried women vote overwhelmingly Democrat, citing the “right” to murder their own babies as a primary issue. This should deeply trouble every thoughtful, Christian conservative. Yet suggest repealing the 19th Amendment and returning to the heavily limited voting rights advocated by the founding fathers, and the negative response from Christians will be more intense than the response to blasphemy against our Creator.

Robust debate is healthy and good for a flourishing society. Disagreement is not a bad thing. But feminism is one of the key culprits that has effectively shut down vibrant debate. All that is required is an accusation of meanness or offense, and the conversation is over before it begins.

Women are experts at leveraging this to our advantage. Men have allowed this to happen.

If America and, more importantly, the church are to recover, we must shed the feminist factory settings and return to God’s blueprint. Men and women are equal in dignity but distinct in design. Women can lead in many contexts — but national headship, church eldership, and family authority are given by God to men.

That is not oppression; it is order. It is not diminishing; it is dignifying. When men and women live according to God’s good design, society flourishes, families strengthen, and the watching world sees something of Christ on display.