Our forefathers prayed on Thanksgiving. We scroll.

There was a time when Thanksgiving pointed toward something higher than stampedes for electronics or a long weekend of football. At its root, Thanksgiving was a public reminder that faith, family, and country are inseparable — and that a free people must recognize the source of their blessings.

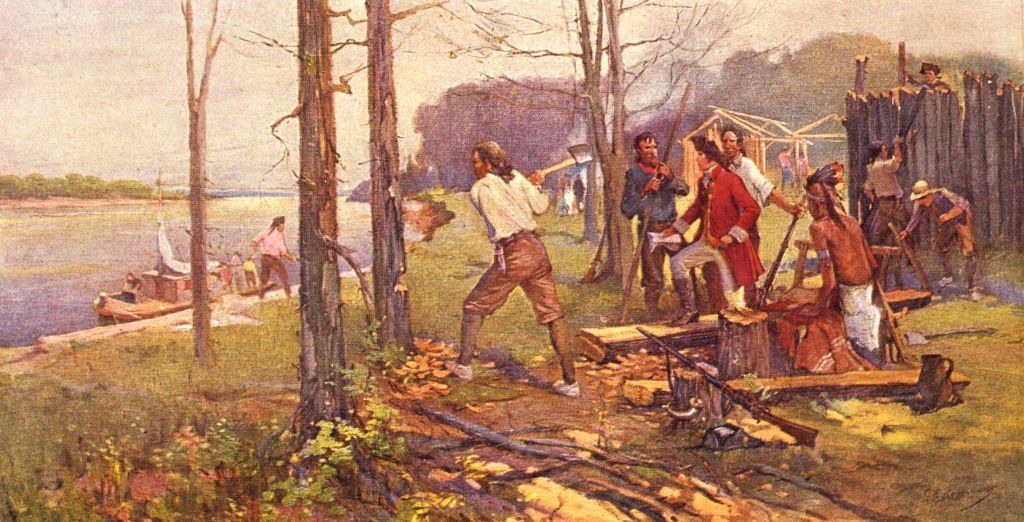

Long before Congress fixed the holiday to the end of November, colonies and early states observed floating days of thanksgiving, prayer, and fasting. These were civic acts as much as religious ones: moments when communities asked God to protect them from calamity and guide their families and their nation.

Grounded in gratitude

The Continental Congress issued the first national Thanksgiving proclamation in 1777, drafted by Samuel Adams. The delegates called on Americans to acknowledge God’s providence “with Gratitude” and to implore “such farther Blessings as they stand in Need of.”

Twelve years later, President George Washington proclaimed the first federal day of thanksgiving under the Constitution. He asked citizens to gather in public and private worship, to seek forgiveness for “national and other transgressions,” and to pray for the growth of “true religion and virtue.”

Our problems — social, fiscal, and moral — are immense. But they are not greater than the God our ancestors trusted.

Other presidents followed suit. During rising tensions with France in 1798, John Adams declared a national day of “solemn humiliation, fasting, and prayer,” arguing that only a virtuous people could sustain liberty. The next year he called for another day of thanksgiving, urging citizens to set aside work, confess national sins, and recommit themselves to God.

For generations, this was the American understanding: national strength flowed from moral character, and moral character flowed from religious conviction.

The evolution of a holiday

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln — responding to years of lobbying by Sarah Josepha Hale — established the last Thursday in November as a permanent national Thanksgiving. Hale saw the holiday as a unifying civic ritual that strengthened families and reminded Americans of their shared heritage.

Calvin Coolidge echoed this tradition in 1924, observing that Thanksgiving revealed “the spiritual strength of the nation.” Even as technology transformed daily life, he insisted that the meaning of the day remain unchanged.

But as the country drifted from an agricultural rhythm and from public expressions of faith, the holiday’s original purpose faded. The deeper meaning — gratitude, repentance, unity — gave way to distraction.

When a nation forgets

Today, America marks Thanksgiving with a national character far removed from the one our forebears envisioned. The founders believed public acknowledgment of God’s authority anchored liberty. Modern institutions increasingly treat religious conviction as an obstacle.

Court rulings have redefined marriage, narrowed the space for religious conscience, and removed long-standing religious symbols from public grounds. Citizens have been fined, penalized, or jailed for refusing to violate their beliefs. The very freedoms early Americans prayed to preserve are now treated as negotiable.

At the same time, other pillars of national life — family stability, civic order, border security, self-government — erode under cultural and political pressure. As faith recedes, government fills the void. The founders warned that a people who lose their internal moral compass invite external control.

Former House Speaker Robert Winthrop (Whig-Mass.) put it plainly in 1849: A society will be governed “either by the Word of God or by the strong arm of man.”

A lesson from history

The collapse of religious conviction in much of Europe created a vacuum quickly filled by ideologies hostile to Western values. America resisted this trend longer, but the rising influence of secularism and identity ideology pushes our society toward the same drift: a nation less confident in its heritage, less united by a common purpose.

Ronald Reagan saw the warning signs decades ago. In his 1989 farewell, he lamented that younger generations were no longer taught to love their country or understand why the Pilgrims came here. Patriotism, once absorbed through family, school, and culture, had been replaced by fashionable cynicism.

Thanksgiving offers the antidote Reagan urged: a return to gratitude, history, and shared purpose.

RELATED: Why we need God’s blessing more than ever

Thanksgiving was meant to be the clearest expression of a nation united by faith, family, and patriotism. It rooted liberty in gratitude and gratitude in God’s providence.

Reagan captured that spirit in 1986, writing that Thanksgiving “underscores our unshakable belief in God as the foundation of our Nation.” That conviction made possible the prosperity and freedom Americans inherited.

Today’s constitutional conservatives must lead in restoring that heritage — not by nostalgia, but by example. Families who teach gratitude, faith, and national purpose build the civic strength the founders believed essential.

A return to gratitude

Thanksgiving calls each of us to humility: to recognize that national renewal begins with personal renewal. Our problems — social, fiscal, and moral — are immense. But they are not greater than the God our ancestors trusted.

That confidence is the heart of Thanksgiving. It is why the Pilgrims prayed, why Congress proclaimed days of fasting and praise, why Lincoln unified the holiday, and why generations of Americans pause each November to give thanks.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared at Conservative Review in 2015.

skynesher via iStock/Getty Images

skynesher via iStock/Getty Images

I don’t mean to sound grabby, but after last week I’ve seen what you can do. Any help to secure a World Cup victory is greatly appreciated.

I don’t mean to sound grabby, but after last week I’ve seen what you can do. Any help to secure a World Cup victory is greatly appreciated.

American poet Ella Wheeler Wilcox's poem 'Thanksgiving' acknowledges that 'Full many a blessing wears the guise / Of worry or of trouble.'

American poet Ella Wheeler Wilcox's poem 'Thanksgiving' acknowledges that 'Full many a blessing wears the guise / Of worry or of trouble.' Only in America are anti-American activists given such liberty to express their disdain for everything our nation represents.

Only in America are anti-American activists given such liberty to express their disdain for everything our nation represents.