History Supports Trump’s Operation To Take Down Maduro

History shows that President Trump is on firm ground when he orders troops into combat – even without congressional approval.

History shows that President Trump is on firm ground when he orders troops into combat – even without congressional approval.There was a time when Thanksgiving pointed toward something higher than stampedes for electronics or a long weekend of football. At its root, Thanksgiving was a public reminder that faith, family, and country are inseparable — and that a free people must recognize the source of their blessings.

Long before Congress fixed the holiday to the end of November, colonies and early states observed floating days of thanksgiving, prayer, and fasting. These were civic acts as much as religious ones: moments when communities asked God to protect them from calamity and guide their families and their nation.

The Continental Congress issued the first national Thanksgiving proclamation in 1777, drafted by Samuel Adams. The delegates called on Americans to acknowledge God’s providence “with Gratitude” and to implore “such farther Blessings as they stand in Need of.”

Twelve years later, President George Washington proclaimed the first federal day of thanksgiving under the Constitution. He asked citizens to gather in public and private worship, to seek forgiveness for “national and other transgressions,” and to pray for the growth of “true religion and virtue.”

Our problems — social, fiscal, and moral — are immense. But they are not greater than the God our ancestors trusted.

Other presidents followed suit. During rising tensions with France in 1798, John Adams declared a national day of “solemn humiliation, fasting, and prayer,” arguing that only a virtuous people could sustain liberty. The next year he called for another day of thanksgiving, urging citizens to set aside work, confess national sins, and recommit themselves to God.

For generations, this was the American understanding: national strength flowed from moral character, and moral character flowed from religious conviction.

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln — responding to years of lobbying by Sarah Josepha Hale — established the last Thursday in November as a permanent national Thanksgiving. Hale saw the holiday as a unifying civic ritual that strengthened families and reminded Americans of their shared heritage.

Calvin Coolidge echoed this tradition in 1924, observing that Thanksgiving revealed “the spiritual strength of the nation.” Even as technology transformed daily life, he insisted that the meaning of the day remain unchanged.

But as the country drifted from an agricultural rhythm and from public expressions of faith, the holiday’s original purpose faded. The deeper meaning — gratitude, repentance, unity — gave way to distraction.

Today, America marks Thanksgiving with a national character far removed from the one our forebears envisioned. The founders believed public acknowledgment of God’s authority anchored liberty. Modern institutions increasingly treat religious conviction as an obstacle.

Court rulings have redefined marriage, narrowed the space for religious conscience, and removed long-standing religious symbols from public grounds. Citizens have been fined, penalized, or jailed for refusing to violate their beliefs. The very freedoms early Americans prayed to preserve are now treated as negotiable.

At the same time, other pillars of national life — family stability, civic order, border security, self-government — erode under cultural and political pressure. As faith recedes, government fills the void. The founders warned that a people who lose their internal moral compass invite external control.

Former House Speaker Robert Winthrop (Whig-Mass.) put it plainly in 1849: A society will be governed “either by the Word of God or by the strong arm of man.”

The collapse of religious conviction in much of Europe created a vacuum quickly filled by ideologies hostile to Western values. America resisted this trend longer, but the rising influence of secularism and identity ideology pushes our society toward the same drift: a nation less confident in its heritage, less united by a common purpose.

Ronald Reagan saw the warning signs decades ago. In his 1989 farewell, he lamented that younger generations were no longer taught to love their country or understand why the Pilgrims came here. Patriotism, once absorbed through family, school, and culture, had been replaced by fashionable cynicism.

Thanksgiving offers the antidote Reagan urged: a return to gratitude, history, and shared purpose.

RELATED: Why we need God’s blessing more than ever

Thanksgiving was meant to be the clearest expression of a nation united by faith, family, and patriotism. It rooted liberty in gratitude and gratitude in God’s providence.

Reagan captured that spirit in 1986, writing that Thanksgiving “underscores our unshakable belief in God as the foundation of our Nation.” That conviction made possible the prosperity and freedom Americans inherited.

Today’s constitutional conservatives must lead in restoring that heritage — not by nostalgia, but by example. Families who teach gratitude, faith, and national purpose build the civic strength the founders believed essential.

Thanksgiving calls each of us to humility: to recognize that national renewal begins with personal renewal. Our problems — social, fiscal, and moral — are immense. But they are not greater than the God our ancestors trusted.

That confidence is the heart of Thanksgiving. It is why the Pilgrims prayed, why Congress proclaimed days of fasting and praise, why Lincoln unified the holiday, and why generations of Americans pause each November to give thanks.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared at Conservative Review in 2015.

What if, in 1968, after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Johnny Carson opened “The Tonight Show” with jibes about how one of King’s own supporters had pulled the trigger? What if he followed with a gag suggesting that President Lyndon Johnson didn’t care much about losing a friend? Or how maybe we need to keep up the pressure on conservatives who think free speech includes engaging those who disagree with them in civil dialogue?

Does anyone believe NBC executives would have shrugged and said, “Let Johnny talk — free speech, you know”? Does anyone think Carson’s 12 million nightly viewers would have treated it as harmless banter and tuned in the next night with curiosity about what he might say next?

Jimmy Kimmel needs to ‘grow a pair,’ take his lumps, and find another venue.

When the members of the first Congress wrote the First Amendment, enshrining freedom of speech, they did it within the context of the words of John Adams: “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

St. Paul puts it this way: “‘I have the right to do anything,’ you say — but not everything is beneficial. ‘I have the right to do anything’ — but I will not be mastered by anything” (1 Corinthians 6:12).

Sadly, I was included in an email from a dear relative who chided anyone who did not protest Jimmy Kimmel’s firing, citing the First Amendment. My relative felt very strongly about this. In his own words, if you didn't loudly defend Kimmel, you needed to “grow a pair.”

My wife and I had just finished watching the entire eight-hour-long, beautiful, uplifting, and spirit-filled memorial service for Charlie Kirk. Before I went to sleep, I decided to clear out my email inbox for the day. Unfortunately, I opened the email from my relative (thinking it was just the usual newsy missive) and read his thoughts.

He had written his opinions before the service, so I am not sure if he would have sent the same message; he made it clear that what happened to Charlie was certainly serious and evil.

My relative used words I had heard before from those who want to virtue signal, while also insisting that doing bad things is not acceptable. It was a variation of this: Yes, what happened to Charlie Kirk was wrong, terrible! But ...

If you hear people on the left — or even people who consider themselves rational, reasonable people “in the middle” who like to play the both-sides-are-wrong card — you need to push back. Comparing the temporary suspension of a mediocre, inconsequential talent like Kimmel to the assassination of a beautiful, influential man like Kirk — well, they are not in the same arena.

Since I was the only one on the email thread who knew Charlie personally (we had been colleagues at Salem Radio), I felt my comments would carry more weight.

I highlighted the Martin Luther King Jr.–Carson comparison and then focused on the “free speech” aspect from a purely business standpoint.

Jimmy Kimmel loses tens of millions of dollars for the network annually. It's been said that his viewership was so low that if you posted a video on X of your cat playing the piano, you could attract more viewers than Kimmel gets on any given night.

Moreover, the claim that Kimmel was denied his First Amendment rights is simply untrue. Kimmel remains free to say whatever he wants anywhere else. For example, when Tucker Carlson (who had the hottest show on Fox, making millions for the network) was canceled for speaking the truth politically, he launched his own “network.”

The funny thing is (no, not jokes from Kimmel’s opening monologues), unsuccessful shows hosted by people with varying degrees of talent get canceled all the time in the world of television. If that were not so, we would all be subjected to the 59th season of “My Mother the Car,”starring Jerry Van Dyke.

RELATED: I experienced Jimmy Kimmel’s lies firsthand. His suspension is justice.

Lackluster shows are replaced by something for which the viewing public actually cares to tune in. The public had clearly tuned out of Kimmel’s show a long time ago.

What Jimmy Kimmel needs to do is “grow a pair,” take his lumps, and find another venue. Nevertheless, Kimmel has (viola!) returned after all, because I suppose the network figures it still hasn’t lost enough money — or influence.

Young Charlie Kirk paid the ultimate price for standing against the obvious evil he saw in plain sight. And in the days, weeks, months, and years ahead, many more, unfortunately, may join him.

My relative closed out his email challenging those of us who didn't agree with him to respond à la Charlie: “Prove me wrong,” he wrote.

I closed my email response to him in a way I think the humble Charlie Kirk might have done: “Jesus said, ‘I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life. No one comes to the Father except through Me'” (John 14:6).

“Prove Him wrong.”

Although America’s 250th birthday is still one year away, there is a fun, unique, and mathematical fact about this year's 249th birthday that will help illustrate just how young America is as a nation.

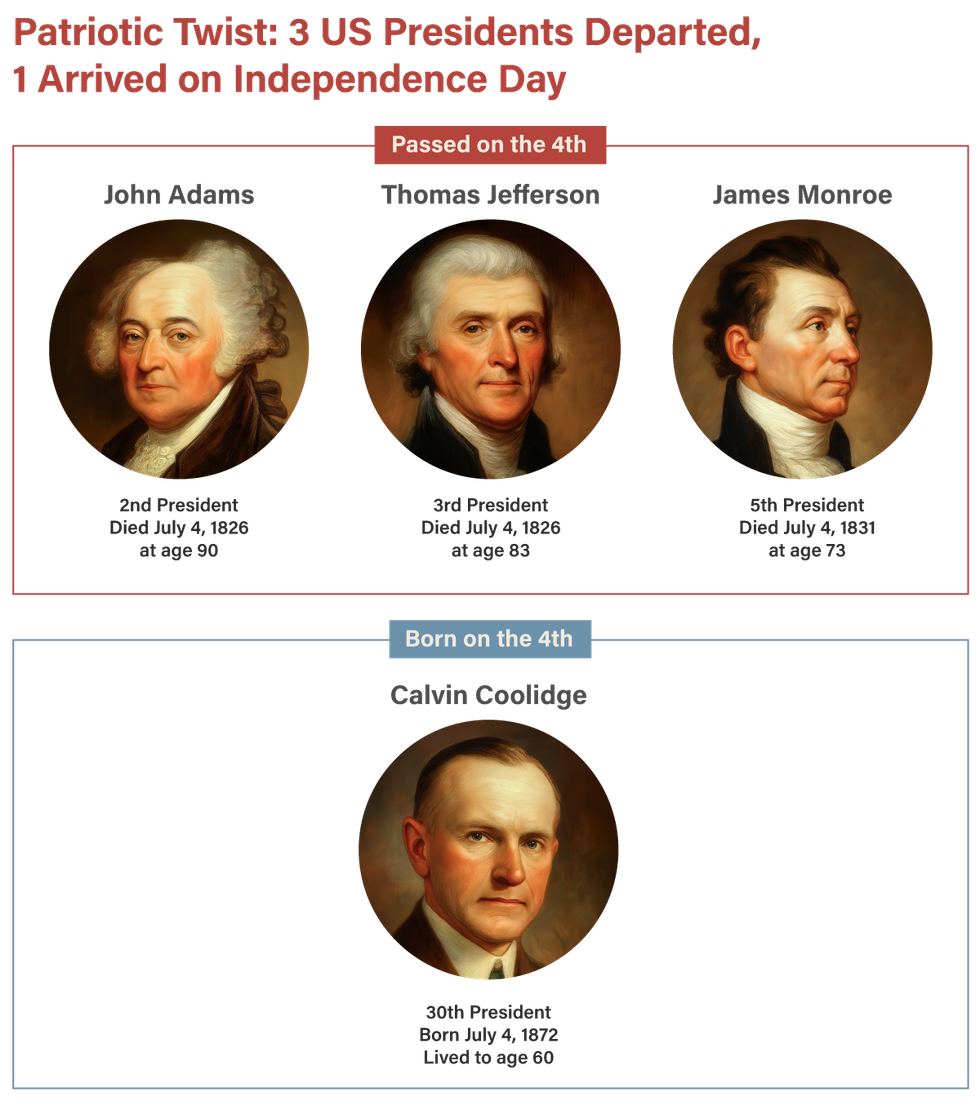

To do that, we can start with the age of President Thomas Jefferson on the day he died — significantly enough, on the day America was celebrating its 50th birthday: July 4, 1826. Jefferson was 83.

Just three 83-year-olds living back-to-back-to-back takes you to the year our nation was founded.

As an interesting aside, our third president was not the only commander in chief whose life was historically tied to America's birthday. President John Adams also died within five hours of Jefferson on July 4, 1826. Five years later, on July 4, 1831, our fifth president and founding father James Monroe also passed away.

Not to be too maudlin, one president was actually born on the Fourth of July. In 1872, Calvin Coolidge came into the world and would grow up to become America's 30th president.

RELATED: Yes, Ken Burns, the founding fathers believed in God — and His ‘divine Providence’

So what does Jefferson’s age of 83 have to do with this year’s national birthday celebration? Well, if you find an 83-year-old person living in America and go all the way back to the year he was born, you would find yourself in 1942. Now, in 1942, find a person who was born 83 years in the past, back to 1859. Finally, find a person born 83 years before that, and you arrive at ... 1776!

Just three 83-year-olds living back-to-back-to-back takes you to the year our nation was founded.

And while we're pondering this age business, it's also fun to look at the relative youth of those who signed the Declaration of Independence, keeping in mind that 56 delegates representing the 13 original colonies actually put their very “lives, fortunes, and sacred honor” on the line when they signed their John Hancock on the document (and, yes, one of them was indeed John Hancock).

Also, with present-day controversy in mind, it is worth noting that none of the representatives signed using an auto-quill.

The average age of the document’s signers was 44 years, which happened to be George Washington's age at the time. And Washington's nemesis across the pond, the other George, King George III of England? He was 38.

The oldest signer of the Declaration was (no surprise) Benjamin Franklin, age 70.

Finally, by now you have probably done the math to figure out the age of Thomas Jefferson — the document’s chief author — when he signed: 33.

Now, enjoy the celebrations and get ready for the biggest one of all, next year’s 250th!

Editor's note: A version of this article appeared originally at American Thinker.

John Adams believed America’s independence should be marked with “pomp, shews, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires and illuminations.” He got his wish. Within a year of the Declaration’s signing on July 4, 1776, celebrations had become a colonies-wide tradition.

The reaction across the Atlantic, however, struck a very different tone.

This wasn’t just about taxes or trade policy. It was about the belief that free men could govern themselves.

The British response was not stunned disbelief or deep introspection. It was mockery — and, ultimately, a grave miscalculation.

The war didn’t begin with the Declaration. A year earlier, in August 1775, King George III had already issued a Proclamation of Rebellion. The crown had stopped viewing the dispute as a matter of political redress. It now saw open revolt.

But the Declaration shifted the terms. What landed in London by mid-August 1776 wasn’t a petition or compromise. It was a bold, philosophical argument for national divorce. In British eyes, it was treason.

British newspapers published the Declaration widely. The London Chronicle printed it, along with other major papers. But few took it seriously. To them, it was just another provocation from unruly colonials.

The elite mocked Thomas Jefferson’s talk of “unalienable rights.” Gen. William Howe, sent to crush the rebellion, called the Declaration “extravagant and inadmissible.” The British state responded accordingly.

RELATED: July 4 exclusive: What we love about America

Within weeks, more than 32,000 British troops — including 8,000 German mercenaries — sailed into New York Harbor. It was the largest overseas force Britain had ever fielded. Howe aimed to stamp out the uprising before year’s end.

The campaign nearly succeeded.

George Washington’s army suffered defeat after defeat, narrowly escaping destruction on Long Island. By autumn, the American position looked hopeless.

But while Britain saw a dying rebellion, France saw a chance to strike.

Even before 1776, French agents had begun quietly arming the colonists. The Declaration gave them a pretext to go farther. Though Louis XVI had no love for democracy, he did have a long memory — and Britain’s victory in the Seven Years’ War had come at France’s expense.

With the Declaration in hand, France could cloak strategic revenge in the language of liberty.

Formal recognition wouldn’t come until 1778, but the shift had begun. French arms, cash, and eventually troops transformed the conflict. What began as a colonial revolt became an international war.

Back in London, the American cause began to attract sympathy in Parliament.

In 1777, future British Prime Minister William Pitt took to the House of Lords to warn his colleagues: “You cannot conquer" America.

He was right.

What Britain failed to grasp was that America hadn’t simply declared independence. It had declared a new theory of government: one grounded in consent, not inheritance.

The crown mistook revolutionary conviction for rhetorical flourish. Britain's government believed the colonists would fold in the face of overwhelming force. But this wasn’t just about taxes or trade policy. It was about the belief that free men could govern themselves.

Ideas like that can stand up to empires — even the most powerful in the world.