![]()

Andrew Patrick Nelson Rides Again

I did not approach this article lightly. I actually went a little overboard in my journey to unveil the film’s mystique.

Since we began our Wednesday Western journey a few months ago, "Stagecoach" has been on heavy rotation. Of the movies I watch obsessively, I have probably watched "Stagecoach" the most, or at least as much as "True Grit" and "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance."

It just never stops being profoundly beautiful. It’s not just the perfect Western; it might actually be the perfect movie. I read everything I could find, dove into the story as deeply as I could. My first draft was 10,000 words long, and it was scattered, chunky, and at times barely coherent. The second draft sank as well. I was wandering the desert, folks. I had begun to feel lost in my own passion for this masterpiece.

So I turned to the Western evangelist himself, Andrew Patrick Nelson, who just began his role as chief curator at Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West, which has been named the top Western museum in the nation by True West magazine. The first part of this article lays out some context that’s useful for the Q&A.

It was an electric conversation. We dove deep, yet we barely covered "Stagecoach" in its entirety.

Here’s the full interview:

Is Stagecoach the best movie ever made? Interview with Andrew Patrick Nelsonwww.youtube.com

(Video and audio used with permission from Kevin Ryan.)

Where you can find it

"Stagecoach" is remarkably easy to find — thank God.

Amazon Prime: Free with subscription. MAX: Subscription. Tubi: Free. AppleTV: $3.99 to rent, $14.99 to buy. Fubo: Subscription. Sling: Free. PlutoTV: Free. Xumo: Free

Coach Ford

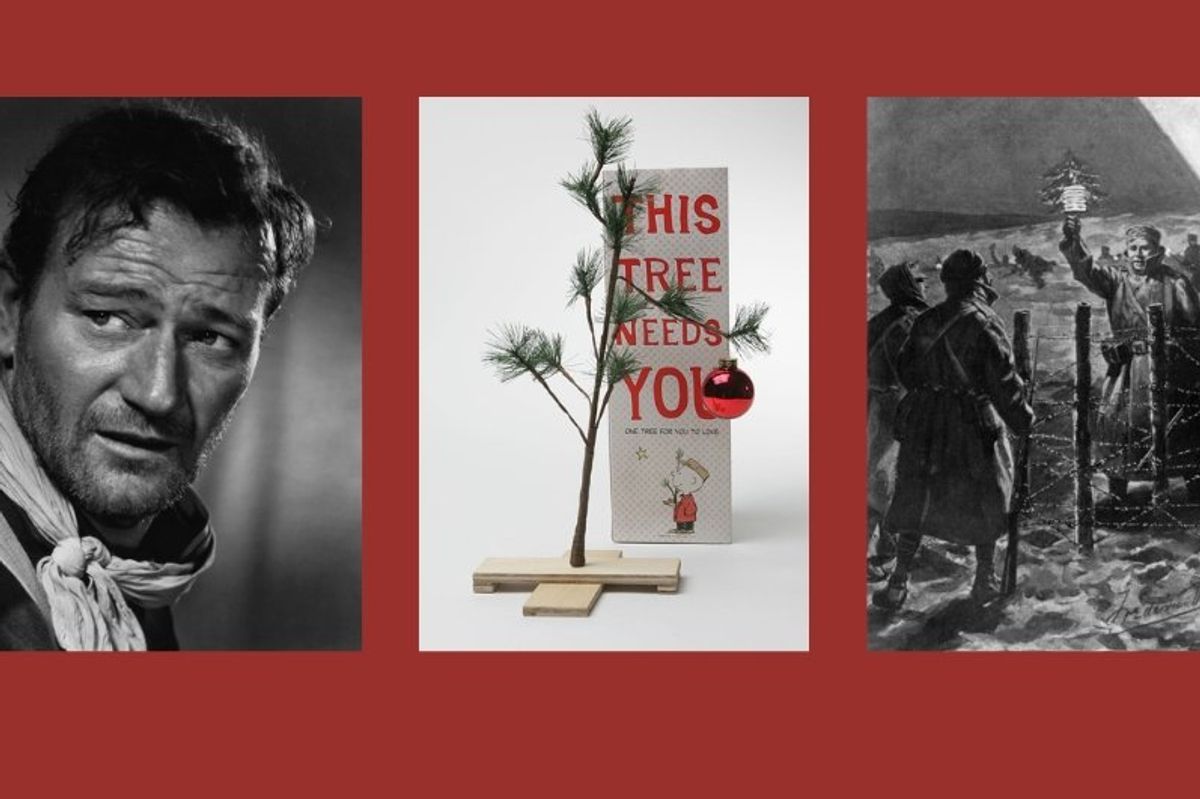

"Stagecoach" was the first of John Ford’s 14 collaborations with John Wayne. It also marked the first Western that John Ford filmed in the iconic Monument Valley on the border between Arizona and Utah, a cinematic choice that shaped the optics of all future Westerns.

![]() Archive Photos/Getty Images

Archive Photos/Getty Images

John Ford, with his record four Oscars for Best Director, had a reputation for being volatile and antagonistic on set. Andrew Patrick Nelson walks us through this more below.

Ford was especially ruthless to the Duke, who viewed Ford as an authority figure deserving a kind of artistic obedience. Ford shaped Wayne's voice, his walk, his reactions. At one point, Ford shouted at Wayne, “Why are you moving your mouth so much? Don't you know you don't act with your mouth in pictures? You act with your eyes."

John Wayne talks about it in Peter Bogdanovich's documentary "Directed by John Ford."

Wayne was 30 years old at the time, with about a decade in the industry. He referred to Ford as “Pappy” and, more telling, “Coach.”

“Took us about a week to make that picture, and it was fun all the way. Pappy always knew how to keep what we call a ‘happy set.’ And I was usually the butt of the jokes on that happy set.”

For all of Ford’s seeming brutality, he truly believed in the Duke. In a letter, Ford said of John Wayne: "He'll be the biggest star ever because he is the perfect 'everyman.'”

"Stagecoach" is itself the ballad of the Everyman. Watching it, again and again, you’ll say, “This is just so good.”

'Stage to Lordsburg'

"Stagecoach" is based on Ernest Haycox’s “Stage to Lordsburg,” a 30-page short story you can read in one sitting. The language is sparse but whimsical in a frontier way. One sentence in particular captures its purpose: “They were all strangers packed closely together, with nothing in common save a destination.”

It captures the brutality of the American West, where people drop dead or collapse without eliciting much of a response. The story offers much less of the liveliness found in the movie’s ensemble approach, where the collective breaks into factions as the stagecoach launches toward Lordsburg.

The film is better than the story, but that’s not exactly fair because the film is one of the best ever made. It is the "Citizen Kane" of Westerns. A cinematic triumph, a genre-transcending film. It lifted the Western genre from the realm of the B movie and raised it to the rank of Hollywood feature film.

Nine strange people

The film somehow manages to feel simultaneously claustrophobic and too wide open.

At its core, it is a human story. The dialogue is as rich as the strife is constant, a dynamism that could just as easily have made it a stage play. In this sense, "Stagecoach" has more in common with "The Breakfast Club" than many of the Westerns that preceded it.

The film’s tagline captures this: “A powerful story of nine strange people.”

![]() United Artists/Getty Images

United Artists/Getty Images

At first, they seem to be Western stock characters. The drunk doctor, the banished prostitute, the stoic cardsharp, the taciturn salesman, the snotty socialite, the judicious marshal riding shotgun, and Buck, played by the wonderful Andy Devine, a John Ford mainstay, the “sweetheart”-repeating driver who could easily have been played by Chris Farley.

John Wayne stars as the kind-natured gunslinger Ringo Kid, who has just broken out of prison in order to avenge the deaths of his brother and father. This is young John Wayne: rail-thin, with a smile that hasn’t been Marlboroed into crease lines.

The film takes place during a stagecoach trek from Arizona Territory to Lordsburg, New Mexico, as Geronimo and his Apache warriors terrorize the area. Despite the danger, nine passengers cram into the Overland stage.

The rivalry between Dallas, the prostitute, and Lucy, the highfalutin snob, is revealing. The clash of femininity is dramatic, like a comparison between the two Marys: Mary Magdalen and Mary the mother of Christ Jesus. There are a ton of flaws with this comparison — Mary never had to learn not to be judgmental, but she did give birth in the middle of nowhere.

But the point is that Dallas, the whore, proves to be supremely maternal. Ford’s brilliance (and it is his, because none of it appears in the Haycox short story) is in how he weaves this revelation into the overall love story of Ringo and Dallas.

Each character undergoes anguish and frustration and joy, among countless other intense emotions.

It turns out to be ahead of its time in several ways. At one point, the acerbic banker, who scurried out of town with a briefcase full of embezzled loot, goes on a moralistic rant, complaining that “what this country needs is a businessman for president.”

Eccentrics trapped on a journey through hell is not an especially new narrative, but it has proven to be an unexpectedly difficult one to pull off well. "Stagecoach" does this and more, revealing the beautiful complexities of human relationships: love, death, and life.

Q&A with Andrew Patrick Nelson

ALIGN: It’s impossible to fully capture why "Stagecoach" is so great, but let’s start with John Wayne’s entrance, when he spins the Winchester and the camera jerks toward him and there's a slight change in his expression.

ANDREW PATRICK NELSON: That's one of the most famous introductions in the history of cinema. It's of course not the first time audiences had seen John Wayne. They'd seen a lot of John Wayne up to this point, dozens of B Westerns by this point.

But the way that that scene is constructed, you kind of get a sense that there's a sound off screen. We go outside, we see characters looking at something, we cut to what they're looking at, and then we get that remarkable push in. There's even a moment where it goes out of focus and then back into focus. This tells us that this is maybe a different John Wayne, and your observation about the grimace is a really good one, that there's a kind of darkness to this character lurking beneath the kind of the boyishness or even the cocking of the rifle as a kind of playful gesture, in some way kind of ostentatious. And that is an important part of the character for the rest of the movie.

You could argue that that's an important part of who John Wayne is for the rest of his career. Somebody who has a kind of a world-weariness, has seen things, kind of has an inner darkness and yet feels compelled to do the right thing.

So there you have Orson Welles telling you that essentially everything you need to know about making movies is in "Stagecoach." And I think there's something to that.

ALIGN: So that was the end of his career in B movies?

NELSON: No, it wasn't. That's the funny thing. You know, people sometimes talk about "Stagecoach" as the movie that relaunched Wayne's career, quite famously, or maybe infamously. He was in a film in 1930 called "The Big Trail." That was the first movie where he got the name John Wayne — he was Marion Morrison by birth. And that film was intended to launch him as a superstar, but it did not do very well for a variety of reasons. So he spends the rest of the '30s making B Westerns for studios like Republic. So in 1939, he's still under contract with Republic.

![]() Fil:The Big Trail (1930 film poster).jpg – Wikipediano.m.wikipedia.org

Fil:The Big Trail (1930 film poster).jpg – Wikipediano.m.wikipedia.org

So he keeps making B westerns for the next, I think, five years or so. It's really not until, I would say, "Red River" is kind of the next real turning point in his career when he's unquestionably an A-list star, one of the biggest if not the biggest star in the world.

ALIGN: What an interesting movie to make him a star.

NELSON: Yeah, well, I think there's some continuity there. You know, a number of biographers of Wayne have sort of zeroed in on "Red River" as the moment that he kind of establishes the template for a lot of his later roles, where he's sort of playing an older man in that point, which he would grow into over the course of the next two decades. He's sort of that melancholy figure, world-weary but also a guide to younger men, a kind of reluctant authority figure. And he plays variations of that particular character in most of his best-known roles from the mid-1940s on.

![]() Universal History Archive/Red River

Universal History Archive/Red River

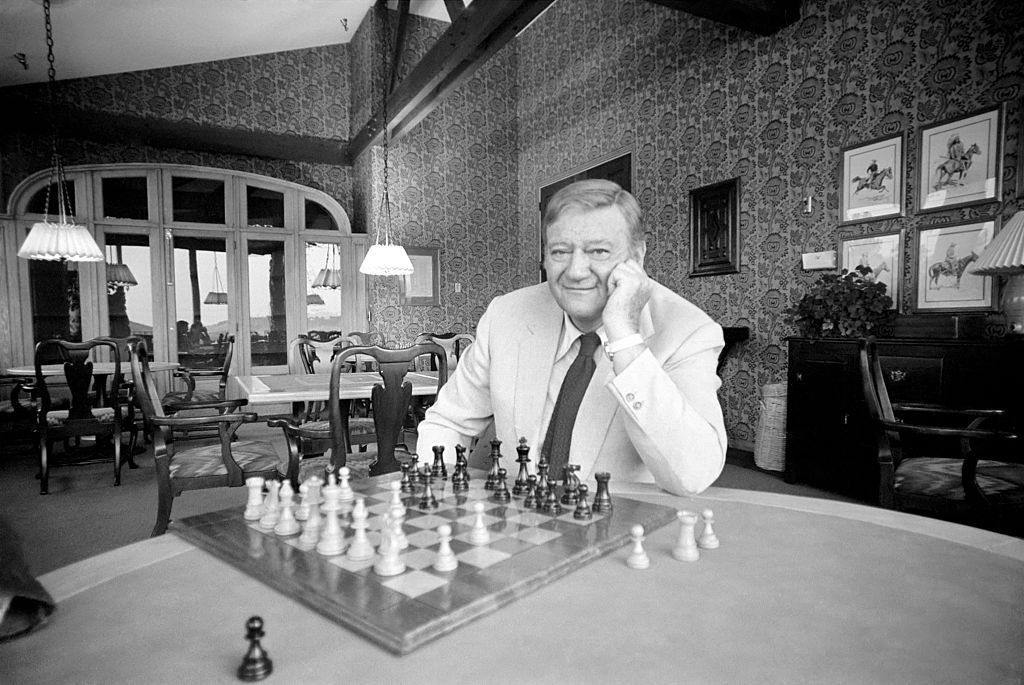

ALIGN: Where does "Stagecoach" stand in the timeline of Ford and Wayne?

NELSON: Ford and Wayne meet each other in the late 1920s. Wayne has some small roles in early Ford pictures, but the standard narrative, and there are people who offer alternatives, is that Ford took great offense when Wayne took Raoul Walsh up on his offer to be the lead in "The Big Trail."

And, you know, Ford and Wayne have an interesting relationship. One way to put it would be kind of adversarial, but one of great respect. I think it's telling that Wayne called Ford "Coach." Because I think that's something of the relationship. So this is a moment where in one telling Ford is letting Wayne come back into the fold, that he has a role for him. It's in an ensemble, so it's not really the protagonist in the sense of getting the most screen time or anything like that.

And Wayne at that point wasn't the most famous actor in the picture. Claire Trevor gets top billing. Thomas Mitchell is very famous at that point. But this is the moment that kind of rekindles something that had begun and continues on.

But again, I'll tell the famous story about "Red River." Supposedly after Wayne makes "Red River," Ford was shown the picture by Hawks and he says something like, "I never knew that big, dumb son of a bitch could act."

And it's after that point that we begin to get pictures like "The Searchers," for example, with Ford and Wayne, or "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance." But you can't overstate the importance of "Stagecoach" and re-establishing what is the most famous and most important actor/director combination in the history of Western movies.

ALIGN: "Stagecoach" is an ensemble film. How does this make it unique as a Western?

NELSON: On the theatrical release poster for "Stagecoach," the tagline is “A Powerful Story of Nine Strange People." Which is a strange tagline for a Western. It's not what you're expecting, right? It isn't it isn't “a thrilling adventure of the Old West" or something like that.

So the context there is important. Around this time, the mid- to late 1930s, Hollywood was really big on ensemble dramas and was big on trying to find stories where you could get a big cast, a couple of big names, but a lot of supporting characters, and confine them in a particular location for the duration of the movie so as to create some drama.

"Grand Hotel" is a famous example of this. So "Stagecoach"; in a way it's "Grand Hotel" out West, where we get this eclectic cast of characters.

And we find a narrative conceit that will keep them together, people who wouldn't ordinarily be together in the same location for a prolonged period of time. So that in a way, it makes "Stagecoach" a kind of different Western because it's not like the Westerns that follow. The imperiled stagecoach doesn't become one of the great conventional Western stories.

It's not the story of the righteous lawman or the antihero outlaw or the wagon train or the building of the railroad or the pioneers. It's very unique in that respect. But it is also important for the Western because of those characters. A few years ago, Cowboys and Indians magazine redid its list of top 100 Western movies. And the senior film writer there is Joe Leydon, who's a friend of mine. And I had him on my podcast, and I asked him about something in particular that happened when he redid the list. So what he did is he made "Stagecoach," in his view, the greatest Western ever and put "The Searchers" down to number two, which I thought very controversial.

So I of course confronted him about this, and you know, his response, in part, and this is a great point, is that in "Stagecoach" you have so many of the conventional Western characters that we would come to associate with the genre. Now they didn't establish these character types, but they certainly cemented or maybe crystallized is a better word. Now, you have all of them there. And even though they don't necessarily appear together in the same configuration, they kind of, I don't know, propagate or proliferate in the Western from this point on.

So in terms of influence, it is difficult to overstate the movie's significance.

ALIGN: As we've talked about before, there's also a connection to some sort of archetype that existed in the West. Let’s start with Doc Boone.

NELSON: In general, Ford is much more interested in society's outcasts, let's say. And it's such that he finds ways to make characters who in a different Western could be an upstanding member of society — the town doctor — into an outcast. His first appearance, we see him inebriated. We see him being kicked out of town. So Ford has a particular facility with that.

And it's something that later filmmakers pick up on, and it kind of makes historical sense because if you're a physician, you had access to alcohol and other drugs. The laudanum-abusing doctor, the ether-abusing doctor. We see that in later Westerns, even in "Deadwood." But it makes what could be a very stock character into a much more complex one, and that's what Ford is really good at.

And that's what the best Westerns do. I mean, you can't say enough good things about Thomas Mitchell's performance, though. It is so moving, the pathos. We just have a great deal of sympathy for this character who has a great moment of triumph in the film where he is able to overcome his vices in the name of a higher calling, maybe the highest calling in his profession. But Ford is not the type of filmmaker to suggest that all of a sudden the character is better. He begins drinking immediately, he kind of descends back into the morass where we found him initially. It's really quite remarkable. And then he continues to have that rise and fall arc. It's really remarkable.

ALIGN: Ford has a lot of boozy humor.

NELSON: Boozy humor. That's a good way of putting it. I mean, one of the most, I suppose, criticized aspects of Ford's films is his preference for a kind of broad humor, slapstick humor, humor that is based in what some might perceive to be ethnic stereotypes. A lot of scenes that revolve around drunkenness and drinking and things of that nature.

And some people see these moments as kind of weaknesses of his movies, but I see them more as his interest in trying to provide us with fully fleshed-out characters, three-dimensional characters who can have moments of sadness and moments of happiness and moments of embarrassment and so on. And that makes for more interesting characters.

So, you know, is Doc Boone as compelling a character if he isn't drunkenly reciting Shakespeare at different moments or insulting people? I mean, we get that, but then we also get these moments of great sadness and pathos. I mean, that's the richness of human experience that Ford is very skilled at offering audiences.

For a film that's less than two hours long, I think it's pretty remarkable how fully fleshed-out the characters are. And again, I think it's that balance of what a recognizable genre like the Western makes possible that we see a character type and we think, “OK, well, we're familiar with this.” Like we're bringing some information.

So there's a certain economy in the storytelling that maybe you don't have to do as much to establish who this character might be or what the profession is, because you can rely on the audience's knowledge. And then that frees you up to spend more time on the nuances, sort of on the complexities. And he does that with really every character trapped in that stagecoach. Each has a kind of arc where they get a comeuppance, they get redemption, they get a moment of heroism.

It's really ... deftly handled because, you know, as you would know, it's hard to tell a story with a lot of characters and do them all justice, which is why we see it so infrequently.

ALIGN: Let’s talk Andy Devine. What a fascinating actor.

NELSON: He pops up in many, many of Ford's films. Devine is a character actor and he has a signature attribute, and that is his his voice. So you kind of hear that voice, there's a very few actors, maybe Walter Brennan is another where, you know, you hear the voice and you think, “OK, well, I know who that is.”

And they're called character actors for a reason, because they tend to play similar characters, but similar is not the same. And, you know, Devine is a different sort of character in "Stagecoach" than when he's playing Cookie as a sidekick to Roy Rogers or something like that. He's a different character in "Stagecoach" than he is in a later picture like "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance."

The point of that character is to help provide a contrast with some of the other characters, while still providing his moment of heroism, his character in "Stagecoach."

He's still wounded. He's still driving the stagecoach with one arm — he still gets his moment of heroism. But broadly, I mean, Devine was there to be the comic relief and to help us appreciate the more stoic qualities, let's say, in some of the people he found himself around. But I mean, a great, great, great performer.

ALIGN: Andy Devine and Ford kind of butted heads on set, right?

NELSON: That's my understanding. Obviously actors are not the characters that they play. You know, sometimes they have a vested interest in making us believe that there's some continuity between who they are and what we see, because we want to believe we're getting something authentic as opposed to a great performance of a piece of deceptive artifice, something like that. But I mean, yeah, Devine can hold his own. And this is one of any number of anecdotes about Ford, who would push people.

He would push them and push them and needle them and he would berate them. And very often it worked, but he would often get actors to this sort of moment where they would finally say "enough" and they would push back. And that's the moment where you probably had earned Ford's respect. Now, today we recognize there are many problems with that type of leadership style.

But in the case of Devine, this was a guy who was able to stand up, and then he has a very long and productive relationship with Ford after this. I mean, he's in almost every Ford Western.

ALIGN: And it's also not unusual. Like Kubrick was notorious for basically bullying some of his actors.

NELSON: Hitchcock falls into that vein too. And, you know, there are complexities here, because if you were to talk to some of the actors, they wouldn't see it the same way as some observers did in terms of the relationships being abusive. But this is one of the challenging things about film history.

There’s a particular dynamic on set with great directors — and this isn't unique to film; this was in the theater as well, the dance, other arts. This idea that you needed not to encourage but to kind of berate people, to get them into a state where they could push themselves, where you could break down certain barriers.

Controversial by today's standards. But I always go back to the fact that when these people looked back on their relationships, working with these directors, whether it's a Kubrick or a Hitchcock, most of the time, they tell a very different story than sort of a straightforward one of hierarchy and abuse and so on. I mean, there are nuances to human relationships. They're complex and troubled, and that's certainly the case with artists, maybe more so.

Maybe this sounds like an excuse, but it's the idea that Ford saw something in Wayne. Maybe he didn't see it as clearly until Howard Hawks had coaxed an amazing performance out of him. But he saw something, and they developed a relationship where he knew how to get great performances out of Wayne. And I think Wayne understood that when he was working with Ford, he was going to be better.

And so he allowed Ford to get away with things that very few other directors could get away with. Maybe Wellman, maybe Hawks, to a lesser degree. But Wayne is a willing participant in this. He understands the nature of the collaboration. And it's hard to argue with what we see on screen. The Wayne we see in "Stagecoach" is in many ways the Wayne of Republic serials.

Many of those B movies do have hints of that darkness, but, you know, Ford brings it out in his direction, his understanding that, for example, characters can convey more just with a glance. There are some really important moments in "Stagecoach" and also in later films like "The Searchers" where all Wayne does is he kind of stares off into space. He just sort of … looks. And Wayne has talked about this as something that Ford encouraged, that he would play some mood music off set, which maybe he is a layover from Ford's silent days. And he would tell him just kind of like look and feel. And in those moments when the Ringo Kid is sitting on the floor of the stagecoach and he's sort of staring off into space he's sort of contemplating the horrible deed that he has to do to rectify the injustice against him.

I mean, there are few moments in cinema just as powerful as that glance. And it's one of a number of glances, right? It goes back to that introduction where we have that look on his face and the dialogue is minimal. I mean, that's the mark of a great filmmaker doing something with variations and getting an amazing, sensitive performance out of an actor that many wouldn't think was capable of that.

ALIGN: I like your use of that word sensitive too, because it's a mix of that. And you can see death on his face a couple of times as he realizes that his father and his brother are dead and he's got to kill two people or three, three brothers, in order to rectify those deaths.

NELSON: That's the tragedy of the Western. You know, I often bring this up when people tell me that Westerns are just straightforward, triumphalist narratives. The Western hero is a fundamentally tragic character, usually because he's, as you said, he's sort of marked by violence and death.

And then he needs to exact some kind of vengeance, but because of his association with violence and death. He actually has no place in the society that he is often helping to bring into being. and "Stagecoach" is a great example. Spoiler alert for those who haven't seen it, but at the end of the movie ... we start in one town, which seems to be full of sanctimonious busybodies. And then we arrive in another town that does seem to have some law and order, but they quickly disappear.

And it seems to be populated solely by gangsters and whores and, as a kind of encouraging vision of what the nascent frontier civilization is going to become, neither is very attractive. And so at the end of the movie, you have the hero and heroine leaving society for Mexico, safe from the blessings of civilization, as Doc Boone puts it. So there's, again, this kind of great tragedy and darkness in the Western; you're going back to these early films, these early sound films like "Stagecoach."

ALIGN: I love Ford’s gift for irony, like you were saying about the Ladies of the Law and Order League.

NELSON: There's no shortage in Westerns of temperance leagues that are sanctimonious and hypocritical. You know, the last time we talked, you asked me about the depiction of religion or Christianity in the Western. And I think I kind of fumbled that answer, but when I thought about it, there aren't a lot of great depictions of preachers, for example, in Westerns.

And I think there's a sort of a general sense, definitely in Ford's films, maybe other great Westerns, that the institutions of man are corruptible because we ourselves are all fallen and we're sinners. And so we can't help but make institutions that are going to be likewise corrupt. I mean, I think most Westerns are about this.

And at the same time, they invoke this idea of a kind of a higher authority, a cosmic justice, that there are these moments when great men of skill and violence, they're not so much ... taking the law into their own hands; they're kind of exacting a type of justice that can't exist on the earthly plane because it's been corrupted, something like that. But that is like a deeply sad and troubling implication of the Western. And yet we see it time and time and time again. And I find that just fascinating.

ALIGN: That's a great transition to another character whom I find fascinating, which is the whiskey drummer whose name I forgot. So that's perfect because nobody remembers his name. Nobody remembers his occupation.

NELSON: So the actor is Donald Meek and the character is Peacock. Now you have timid, nervous, another great performance that comes out in, you know, the stutters, the slips, the inability in most cases to stand up to Doc Boone.

The interesting character, the whiskey drummer again, who could be a very conventional character, but we get a guy who's nominally from the East, even though he keeps making the distinction that he's not from Kansas City, Missouri, he's from Kansas City, Kansas. And we understand that one is east and one is west, baby. So he's at least conceptualizing himself in this way. And he again has one of these great moments where he becomes the kind of conscience of the picture at a particular junction.

But that is followed up with when they're crossing the desert and the wind is blowing and they're all caked in dust and Boone has started drinking again, and he tries to get Boone to stop, but he can't.

ALIGN: Talk to me about Ernest Haycox.

NELSON: Ernest Haycox was a prolific writer, mostly of short stories, especially in the 1930s and '40s. But before and after that, I think he has over 300 credits to his name, wrote mostly in Collier's weekly in the '30s and then switched over to the Saturday Evening Post.

And there's a writer named Richard W. Etulain who has written a really good book about Haycox. So if people are interested in him, that's the book to read. You know, he makes a case that what Haycox was able to do is kind of elevate the Western from a sort of formulaic and somewhat lowbrow form of popular fiction to something that was more sophisticated and respectable. And he did that in a number of ways.

His attention to history and historical details was somewhat different. His interest in three-dimensional characters, let's say. So he's a major figure in the popularization of not only the Western but also a particular type of Western that lent itself well to serious cinema in some cases. "Stage to Lordsburg" was a story published in Collier's magazine in 1937. Probably his most famous work is the basis for "Stagecoach."

And as you mentioned earlier, the movie is different from the story in many ways. It's cinematic in ways that the story is not, but very important. Let's see. "Troubleshooter" was a story from 1936 that became serialized as "Union Pacific," another Western released in 1939. So, you know, in this important year for Western movies, it's telling that two of those movies have their inspiration in the work of this one great writer.

ALIGN: Any final words on "Stagecoach"? We barely touched it. We dove in deep. We had a deep discussion and yet just barely touched the surface.

NELSON: I think it's an important film. I think there's so many stories told about it. Maybe the one to end on is the Orson Welles anecdote, where famously Orson Welles in his early 20s was, in the late 1930s, given kind of an unprecedented contract by RKO studios to make movies.

He had proven himself as kind of wonder kid of the theater and was given almost complete authorial agency over the production of a film, and he of course had very limited experience with motion pictures and yet was able to turn out "Citizen Kane," you know, which many would argue is the greatest film of all time. And when Wells was asked how did you learn to make movies, he would say that he just watched "Stagecoach" over and over and over again. So there you have Orson Welles telling you that essentially everything you need to know about making movies is in "Stagecoach." And I think there's something to that. It is very easy to find one particular thing about the film and to go very deep.

And then you begin making connections between that one thing and other things, and you understand just how thoughtful and sophisticated the picture is. So it may not be as good as "The Searchers," but it is hard to name many Westerns better than "Stagecoach."

Broken Bow Country: Meet the 17-year-old behind a viral Western clothing brand

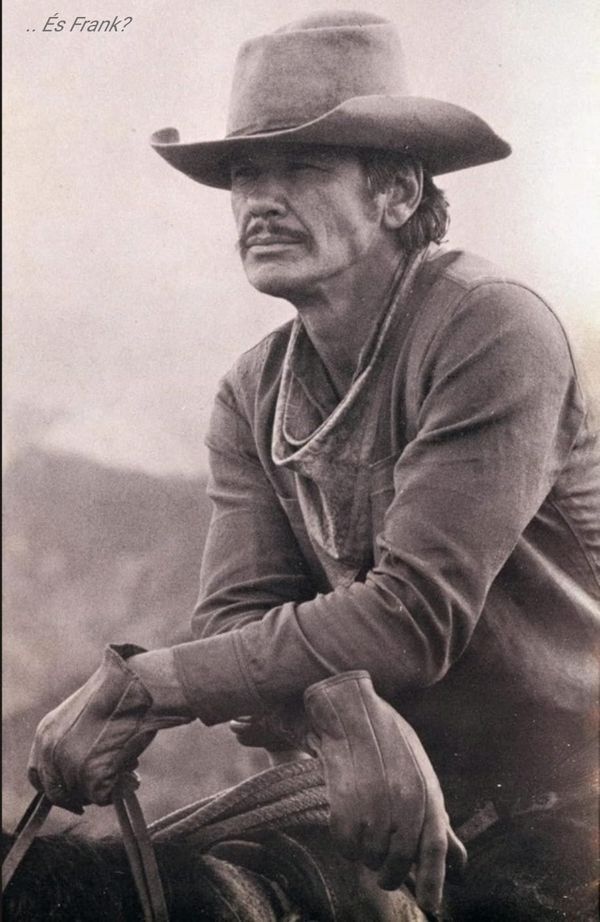

Broken Bow Country: Meet the 17-year-old behind a viral Western clothing brand Back to the old western | Charles Bronson as Chino in classic western film 'The Valdez Horses' in 1973 | Facebook

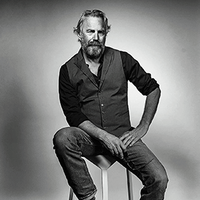

Back to the old western | Charles Bronson as Chino in classic western film 'The Valdez Horses' in 1973 | Facebook Kevin Costner & MW (@modernwest) on X

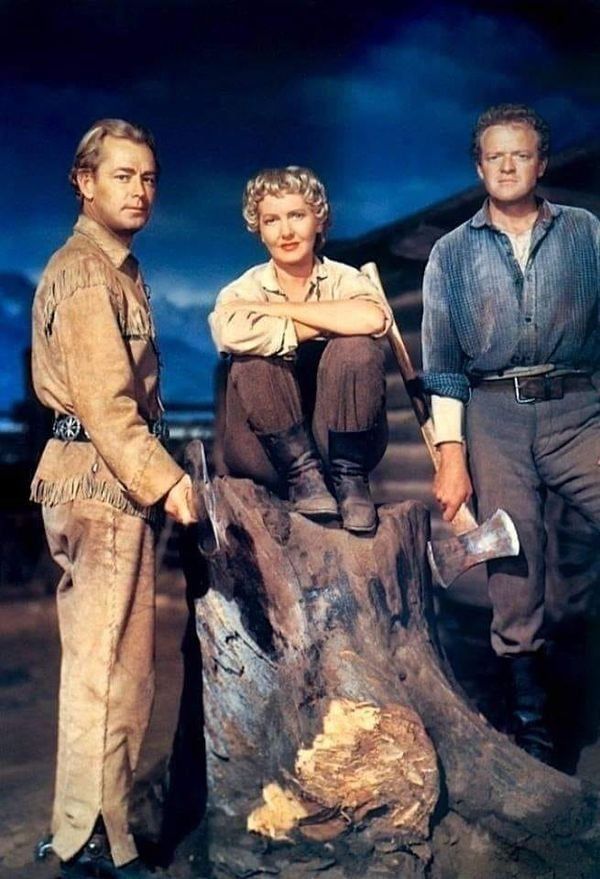

Kevin Costner & MW (@modernwest) on X Best cowboy movies forever | Alan Ladd, Jean Arthur, and Van Heflin in "Shane" (1953) | Facebook

Best cowboy movies forever | Alan Ladd, Jean Arthur, and Van Heflin in "Shane" (1953) | Facebook

Archive Photos/Getty Images

Archive Photos/Getty Images United Artists/Getty Images

United Artists/Getty Images Fil:The Big Trail (1930 film poster).jpg – Wikipedia

Fil:The Big Trail (1930 film poster).jpg – Wikipedia Universal History Archive/Red River

Universal History Archive/Red River Moviegoers consistently appreciate characters like John Wick, the noble outlaw, the cowboy in a bulletproof Armani suit.

Moviegoers consistently appreciate characters like John Wick, the noble outlaw, the cowboy in a bulletproof Armani suit.