![]()

Does the name Jonathan Keeperman ring a bell?

What about Lomez, the pseudonym Keeperman has used over the past few years while amassing 75,000 followers on X and building a successful publishing company?

'We investigated and reported out the identity of a leading far-right commentator who publishes and platforms prominent racists. ... That isn’t doxxing — it’s straightforward coverage of the most influential political movement in America today.'

Keeperman's online presence is a bit too small-scale to qualify him as an "influencer," and the readership served by Passage Publishing, while growing, is still rather niche. The former high school basketball star lives a quiet life centered on work and family — hardly the profile of someone courting fame. So there's a decent chance you don't know him.

But at least one journalist-activist thinks you should.

G'day, anon!

Earlier this month, a Portland, Oregon-based Australian writer named Jason Wilson published an article in the Guardian under the breathless headline "Revealed: US university lecturer behind far-right Twitter account and publishing house."

Although somewhat grandiosely billed as an "investigation," Wilson's piece confines itself to one simple question: Who is the anonymous writer and publisher known as "Lomez"?

The intrepid muckraker expends 3,000 words to provide the answer, which would seem to be of little interest to anyone outside a certain segment of the very online: Lomez is Jonathan Keeperman, a 41-year-old native Californian with an MFA from UC Irvine, which subsequently employed him as a lecturer in the English department.

Wilson pads his expose by rehashing Keeperman's rise to prominence under this name, noting that his "far-right" X account had managed to amass a modest but respectable 55,000 followers in recent years. Nor does Wilson fail to mention the growing success of the company Keeperman founded in 2021, Passage Publishing.

But all of this was already common knowledge to both Keeperman's supporters and detractors. The bulk of Wilson's reporting consists of clicking his way through public statements that are not in themselves especially incriminating: the X post in support of Kyle Rittenhouse, the articles for the American Mind and IM-1776, the popularization of "longhouse" as a metaphor for feminist overreach.

At times Wilson's penchant to disseminate the obvious leads him to serve as a kind of guerrilla marketer. He dutifully he rattles off a number of the authors whose works are available for purchase on the Passage Publishing site, some of which he notes appear in "lavishly produced" deluxe editions.

Wilson betrays his desperation to make something of this perfectly unremarkable commercial activity when he asks one A. James McAdams, a political scientist who researches "far-right thinkers," to weigh in on what possible motive Keeperman could have had to start a business.

“This is a source of money,” comes the expert response. “The general public does not know about Ernst Jünger, but you can sell his books to the far right, and you can make money.”

Far more rigorous is Wilson's careful assembly of evidence tracing the Lomez identity back to Keeperman. The reporter tracks his quarry down a twisting trail of Whois lookups, LegalZoom LLC filings, and burner Twitter accounts.

Cross-checking biographical details mentioned by the Lomez persona with public information about Keeperman reveals extensive parallels. Both Lomez and Keeperman are third-born children who excelled at high school basketball; both have a father who died in autumn 2022.

Wilson's "Deep Throat" is a former UCI colleague who listens to Lomez podcast appearances and identifies the voice as Keeperman's.

Master of the doxx-posé

Eventually, the reader wearies of all this journalism. He realizes that these meticulously sourced facts won't add up to anything bigger. There's no crime or grand conspiracy at the bottom of this rabbit hole.

For Wilson, stripping Keeperman of his anonymity is its own end. Which makes his article a perfect example of a relatively new nonfiction form, as revolutionary in its way as "New Journalism" was in the '60s. Let's call it the doxx-posé.

The practice of doxxing originated with hackers, who would self-police their community of digital outlaws by broadcasting the identity of anyone who stepped out of line. It later came to mean the publishing of a public figure's personal information (a policeman's or judge's home address, for example) with the implied threat that others would use that information to do the figure harm.

Like its antecedents, the doxx-posé is essentially malicious in intent; what makes it particularly weaselly is the way it disguises that intent as a high-minded act of journalism. The doxx-posé writer pretends to uncover a newsworthy truth without ever explaining why that truth is important.

After all, what's wrong with publishing under an assumed name? There's a long tradition of using pseudonyms and a variety of perfectly respectable reasons for doing so. In 1996, then-Newsweek editor Joe Klein released his Clinton campaign roman à clef "Primary Colors" under the nom de plume "Anonymous." Doing so, Klein recalled a few years ago, gave his novel "a mystical power I hadn’t imagined."

I’d held back my name partly as a goof, an homage to pseudonymous 19th-century serial novels. Benjamin Disraeli and Henry Adams, among others, had employed the conceit; "Sense and Sensibility'" was written by "A Lady.'" To my amazement, members of Clinton’s team began accusing one another of having written it.

The intrigue surrounding it helped the gossipy "Primary Colors" sell millions of copies.

The doxx-posé writer has no time for such genial parlor games. He writes under the assumption that anonymity is no longer a laughing matter. The Lomez mask conceals not a mischievous wag but a kind of terrorist, who uses language to harm the body politic. And so the mask must be removed.

We know this not because Wilson bothers to explain why Keeperman is a threat but because he describes Keepernan with the same vague, meaningless labels with which the left identifies all its ideological enemies: "proto-fascist," "far-right," "anti-LGBTQ+."

The article's sole accomplishment is to attach these shorthand accusations to a real name. And what are we supposed to do with this information? Wilson insinuates that Keeperman's position as a "university lecturer" (he left the job in 2022) was somehow incompatible with his online activities, without explaining why. If there were a conflict of interest, its up to the reader to imagine it.

More creepy is the message Wilson sends by digging into Keeperman's personal life: calling his home, linking to his wedding pictures, looking up property he owns. Ostensibly this is in the service of verifying Keeperman's identity, but the subtext is clear.

Pretty nice life you got here, Mr. Keeperman. It would be a shame if you said anything to ruin it.

When a doxx-posé does upend its target's life, the damage it inflicts retroactively legitimizes the the doxx-posé writer. The punishment proves the guilt. They fired him? I guess he was doing something wrong.

Who doxxes the doxxers?

Align contacted Wilson via email to ask why Keeperman's identity was newsworthy enough to justify a 3,000-word article in a major newspaper. Rejecting the characterization of his article as "doxxing," Wilson replied:

"We investigated and reported out the identity of a leading far-right commentator who publishes and platforms prominent racists, and used anonymity to make threats online and direct unfriendly attention at events in his own community. That isn’t doxxing — it’s straightforward coverage of the most influential political movement in America today."

Wilson's response is disappointingly — yet typically — circular. As in his article, the epithet "racist" is meant to be self-evident, requiring no further proof or explanation. Then there's the nefarious use to which Keeperman allegedly put his anonymity. Lomez's raison de posting seems to be no different from that of countless other, often more prominent anons: making "offensive" jokes and expressing unpopular beliefs.

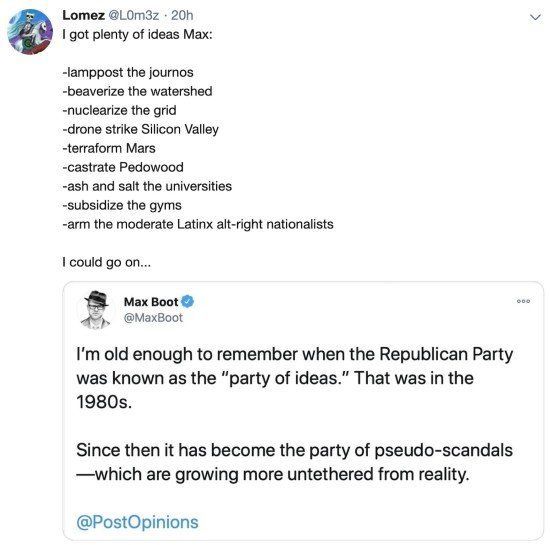

As an example of Keeperman's online "threats," Wilson's email to Align links to an archived post responding to pundit Max Boot's call for a reinvigorated GOP:

![]()

Wilson links to the same post in his article, quoting the first entry in the list and soberly describing it as "an apparent call for summary lynchings of members of the media." He fails to quote any subsequent entries, however, leaving the reader to wonder if he regards proposals to "beaverize the watershed" and "arm the moderate alt-right Latinx nationalists" as little more than idle japes.

As an example of Keeperman "direct[ing] unfriendly attention at events in his own community," Wilson links to a post in which the sometime Montana resident offers critical commentary on an upcoming "family friendly drag show:"

— (@)

While this post failed to make the final cut of Wilson's article, it clearly catches Keeperman in the act of inciting his followers. He openly urges them to question just when drag's raunchy, hypersexualized parodies of femininity supplanted balloon-twisting party clowns as optimal children's entertainment.

Physiognomy check

In Wilson's defense, his article does fail to meet the criteria for doxxing in one crucial respect: Keeperman seems to have suffered few if any negative consequences as a result of his big unmasking.

If anything, Wilson's well-wrought doxx-posé seems to have improved Keeperman's fortunes, prompting multiple displays of solidarity from friends and acquaintances and gaining him more than 20,000 new followers on X.

In post after post, Keeperman supporters marveled at how Wilson inadvertently pulled off a strange kind of reverse character assassination.

Revealed: Lomez is tall and handsome. He can dunk a basketball. His UC Irvine students loved him. His wife is beautiful.

Less kind posters couldn't resist the opportunity to compare Keeperman's chiseled, square-jawed visage to the headshot accompanying Wilson's Guardian bio.

Coming out as Keeperman was also a boon for business. Passage Publishing was quick to capitalize on the publicity by offering free shipping for Steve Sailer's "Noticing" with the cheeky promo code "Wilson." Said anthology soon climbed the Amazon Kindle charts, becoming the number-one new release in "golf" and "statistics" and reaching number two in "social policy."

— (@)

Align originally reached out to Keeperman on May 13, the day before the Guardian article appeared. Our intention was to profile him as a rising entrepreneur.

Neither of us had any way of knowing that fate — in the form of a Media and Communications PhD turned streetwise, immigrant cybersleuth — was about to add a shocking new chapter to Lomez lore. The following interview was conducted via shared Google doc over the period from May 14 through 23.

ALIGN: Is “Lomez” a "Seinfeld" reference? I’ve always wondered.

JONATHAN KEEPERMAN: It is a "Seinfeld" reference. Decades ago, when I started posting on the internet, pre-Twitter, I needed a handle. I must have recently watched a "Seinfeld" episode where Lomez, one of Kramer’s off-screen friends, was mentioned. It was a unique name and, I thought, suitable for an anon.

ALIGN: Jason Wilson's "Guardian" article about you cites one A. James McAdams on your possible motivations for starting Passage Press:

“This is a source of money. The general public does not know about Ernst Jünger, but you can sell his books to the far right, and you can make money.”

Selling books to make money? How accurate a description is this of the Passage Press business model?

JK: What an incisive observation. I don’t know how Dr. McAdams was able to pull back the curtain on our nefarious scheme. No wonder he’s a tenured professor at a prestigious university! Our original business plan was to give our books away for free, and when the communist revolution comes we will be prepared to do our part, but alas, for now, in the pre-dawn of our coming utopia, we have to pay our bills.

McAdams’ comments in the article really are the smoking gun for how utterly corrupt American intellectual life has become. The fact that he calls Ernst Jünger a “far-right” figure, as if to dismiss such a great man’s work with this meaningless phrase, demonstrates these people's utter lack of seriousness. They are either illiterate, willfully ignorant, or brazen liars. I don’t know which of those is worse, and I suspect it’s a combination of all three.

Jünger is one of the most brilliant and complex writers of the 20th century. "Storm of Steel" is perhaps the most profound firsthand account of the experience of war that has ever been written. Jünger’s writing on art, religion, philosophy, and the totalizing tendencies of modernity transcend the petty ideological games these people demand we play. No wonder they hate him. Anybody with a soul will take great comfort in Jünger’s writing and be elevated by him. Truthfully, it breaks my heart that people who presume to be our intellectual betters have failed so spectacularly and stooped to such bottom-feeding invective. They are unworthy of uttering Jünger’s name.

ALIGN: But seriously: What are the economics of publishing like these days? On the one hand, I assume printing on demand saves money; on the other hand, nobody reads books. On the other other hand, you can more easily target the audience who is interested in your book without big, wasteful marketing campaigns.

JK: Publishing is a difficult business that really only works at volume. That’s why it’s such a hard industry to break into. You capture small margins and have to sell a lot of books before you can break even. That is the old logic, anyway.

We’ve found a new model for selling books that captures both the luxury consumer who values nice physical objects made with care and the price-sensitive consumer who just wants to read a regular old paperback. So this means on the one hand selling small-batch, hand-crafted books with very fine materials at a premium (our Patrician Editions), and then selling a paperback version once those are accounted for.

Just how much this model can scale is anyone’s guess, but so far we’ve sold out of everything we’ve printed, so we will continue down this path until the market tells us otherwise.

ALIGN: Could you describe — in as much detail as you can bear — the origin of Passage Publishing? Did it start with the more or less spontaneous announcement of the Passage Prize in response to a Twitter exchange?

JK: “The more or less spontaneous announcement of the Passage Prize” is correct. I did not set out to start a publishing company. As recent reports confirm, I had a comfortable job as an academic and wasn’t trying (at least not consciously) to find an escape hatch.

Around mid-2020 or so, just as COVID hysteria was peaking, I began to observe that culture was stuck. Not stuck accidentally, but as a result of systematically excluding certain types of art and stories from certain types of people.

This was not a novel observation. I think just about everyone, from every corner of the culture, was feeling and even saying the same things. So I thought, "Why not try to do something about this, however modest?"

My idea was to take $10,000 of my own money and put it up as a prize for an art and literature contest. I wanted to see what kinds of talent I might be able to dredge up from the online ferment.

The project then took on a life of its own. Long story short: I ended up receiving over 2,000 submissions and raising another $10,000 in prize money. I had some great judges helping me along the way; they deserve as much credit as anyone for the project's success. We turned the winning submissions into a book and sold out the entire print run, which created enough revenue to fund the second prize.

It was obvious at that point that we were on to something. But I hadn’t yet taken a cent from the project; in fact, I'd lost a not insignificant amount of money along the way. I knew that if I wanted to sustain this work, I’d have to start thinking a little bigger. That’s when I formulated the idea for a proper publishing company, and the rest, as they say, is history.

ALIGN: Was Michael Anton’s article “The Tom Wolfe Model” an influence on Passage Publishing?

JK: It was. I had the idea for something like the Passage Prize for awhile, and there are some old threads of mine on Twitter where I’m speculating about what new patronage networks for art and culture might look like, but Anton’s essay really catalyzed my thinking and helped validate my hunch that I was not alone in these thoughts.

ALIGN: How do you pay authors? Publishing, like music, is one of those industries people often speak of as “broken” — especially when it comes to artists making a decent living. Do you see what you’re doing as offering any kind of replicable, long-term solution?

JK: We are experimenting with royalty structure and have a current model that breaks slightly from the Big Five. Paying our authors is of course important, but what the industry needs to figure out is what value a publisher actually adds for writers, many of whom have large enough social media followings to serve as their own marketing apparatus.

One thing we do is make really high-quality physical books that writers can’t make themselves. We’ve also had a lot of success with events and readings that get authors in front of a paid audience. We are building a community around our writers and readers that is different from anything mainstream publishers are doing (or frankly capable of doing).

ALIGN: What kind of marketing does Passage Publishing do? Does having a relatively large follower count on X allow you to rely mostly on “word of mouth”?

JK: So far, word of mouth on Twitter has been our best and really only form of marketing. At the scale we are at, this works, and our audience has continued to grow.

Big social media flash points like Steve Sailer’s ongoing dispute with Will Stancil, or my recent micro-moment in the spotlight, help get us in front of even more eyes. We believe in our work. And we believe that readers, wherever they may be, who find our stuff will be impressed enough to stick around to buy the next thing.

Brick by brick. Organic growth. Keep publishing great books. That’s the formula. That’s the tweet.

ALIGN: Do you deal with any kind of censorship? I was able to find "Noticing" on Amazon; then again, it’s “not available” for whatever reason.

JK: So far we have not dealt with any institutional censorship. Amazon, with a few notable exceptions, has been pretty good in the past about allowing all sorts of books on their platform. I don’t foresee that changing, though it’s possible I’m being naive.

We know we will be under fire — see the Guardian’s hysterical reporting as an example — but we are agile. We control most of our own production and distribution. If bottlenecks around censorship show up, we will pivot and find solutions.

ALIGN: How important is Amazon to independent publishing? Self-published writers have told me it’s essential, like it or not. Is it different for you?

JK: We only started selling books on Amazon a couple of weeks ago. Our direct sales model from our website has sustained us so far. But yes, Amazon is a behemoth. I don’t know that a book business can thrive without them. But again, if Amazon decides to take radical action and start censoring Ernst Jünger, I suppose we will adapt to that too.

ALIGN: What kind of administrative etc. overhead do you have? I assume you can just use ready-made ecommerce tools (I could be wrong)? What about editing and design? Marketing? Printing?

JK: There are ready-made services that can do some of this stuff, and AI may help with some design and editing efficiencies, but there is nothing like the human touch. We have a lean staff, but we do have a staff. We also work with a handful of designers and editors on contract. Normal startup environment, I suppose.

ALIGN: I particularly like the design of the three Peter Kemp covers. And for different reasons, the cover of “Noticing” — something about that featureless silhouette evokes the '70s educational TV programming of my youth.

JK: Yes, our designers are really incredible artists, two of whom I found through the Passage Prize. Book design in general, like the rest of the industry, is mostly pretty dull. These book covers all more or less look the same and speak to a bygone era of information design. Like with everything else we do, we want to shake up the visual landscape. We want books that really stick out on your shelf. Our design for Nick Land’s "Xenosystems" is a great example of this. But then, not all authors should be treated with this approach. Steve Sailer is not Nick Land, and his style of quiet, reasonable punditry needs a visual language to match.

ALIGN: Is it possible (or advisable) to have handshake (or very simple) legal agreements with writers — or do lawyers need to get involved?

JK: I value a firm handshake as much as the next guy, but just as good fences make good neighbors, good contracts make good business partners. That’s been my experience, anyway.

ALIGN: Many of the works you publish are public domain. All curatorial taste and market savvy aside, is publishing authors like Conrad, Jünger, and Kemp as easy as choosing what’s out there, “cutting and pasting” and then repackaging?

JK: It could be that easy, but again we want to offer value to our readers they can’t get elsewhere. Anything we publish will come with something that has a Passage signature. In our new collection of stories from H.P. Lovecraft, for example, we commissioned the great comic artist Alex Wisner to create original drawings for each story. In our forthcoming three-volume set of Robert E. Howard books, we commissioned a scholar on his work to craft new introductions and contextualize Howard’s work.

ALIGN: I assume the company takes its name from Jünger’s “The Forest Passage.” Could you describe what that book means to you — and how it speaks to Passage Publishing’s mission?

JK: That’s correct. I think Jünger’s "Forest Passage" is one of the most important pieces of writing of the last century and is perhaps more relevant now than ever. The book asks what it means to stand apart from and outside a totalizing cultural and political leviathan, one that wants to reduce us to meek, unrelenting surrender.

Jünger describes this state as omnipresent and all-seeing. Even worse, it's impossible to locate — it surrounds you like a miasmatic fog. To me, that image is quite powerful. As is the place Jünger proposes as an alternative: the wild, undomesticated forest where men — “forest rebels” in Jünger's parlance — can gather the imaginative and moral courage to find their way to something new. This is the whole concept of Passage in a nutshell.

ALIGN: Most of the works you republish seem to have developed a certain following on the “dissident right” (or what have you). To what extent are you reacting to what the “scene” is talking about, and to what extent are you introducing books and writers to them?

JK: We are not reacting. There are a certain number of writers that have gained meme status on the right — Evola and Spengler come to mind — and there is certainly nothing at all wrong with reading those guys or publishing them, but we have our own vision, our own canon of forgotten or what I call “obscured” writers that we are trying to reintroduce to the public.

We are starting from the premise that people’s mental models for the world are broken or at least woefully incomplete. Their understanding of history has been purposefully constrained and intended to nudge people toward very particular conclusions about how we are supposed to think and act in the current year. People are carrying around these narratives without even realizing it. We want to disrupt that. We want to jar those closed-off spaces open and allow for a fuller picture of the world to come through.

ALIGN: One thing I’ve noticed about many of my “normie” friends — regardless of their politics — is this untroubled assumption that all of the old cultural gatekeeping institutions are both still relevant and still functional. Even conservatives who know enough to bash CNN and “fake news” don’t know or care who Steve Sailer is, for example. If he had something important to say, he’d have a TV show or write Ann Coulter-level best-sellers.

JK: Yes, it’s a curious thing. I’ve written about epistemic authority quite a bit and how officialdom gets cemented in the collective consciousness. Who produces truth? Conservatives laugh at the left when they ask this question, as if it’s just some postmodern gobbledygook — the truth is the truth, after all. But it's highly salient.

When we look at any event — be it January 6, the pandemic, George Floyd’s death, etc. — we are inevitably dealing in matters of interpretation. Even the driest, most just-the-facts-ma’am summary of these events has normative implications based on what facts are included and what aren’t.

And in every instance, the official narrative about "what happened" gets constructed by a web of self-reinforcing institutions that all share a very narrow ideological framework. [Passage Publishing author] Curtis Yarvin famously calls this web of institutions the cathedral. We need to jam these networks up and offer an alternative web of self-verifying channels of information.

ALIGN: The lack of curiosity seems even more pronounced when it comes to literature. I know I used to write off the idea that anything artistically worthwhile was happening online. Wondering what your experience was in realizing its potential— especially as someone who explored the more traditionally credentialing MFA route.

JK: There’s a temptation to think you are slumming it by writing and growing an audience online, that there is something lesser about this ecosystem than what is on offer in normie publishing. I reject this totally. The normie lit world (with certain exceptions, among them friends of mine who have succeeded there) is just mind-numbingly boring.

There is no risk-taking. No wildness. It is a sewing circle. So the online world has been a blessing. There is tremendous raw talent and a readership that actually cares about ideas. I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

ALIGN: While I’m on the topic, did you go through an analogous red-pill conversion at some point?

JK: No real red-pilling for me. My path is somewhat unusual in that I’ve more or less always been on this side of the fence. I was reading Sailer when I was 20 years old. While I was no fan of Bush in high school, I would side with Pat Buchanan when I’d watch "The McLaughlin Group" with my dad (much to his dismay), and I always cited Richard Nixon as my favorite modern president. Granted, the latter was something of a troll ... at any rate, I'm not sure what formed my political inclinations. I think I was just born this way.

ALIGN: I follow a lot of marketing guru accounts on X, and one consistent theme is the counterintuitive popularity of “high-ticket offers” — people want to pay a lot of money for something you tell them is worth it. Is that your experience with the Sailer “Patrician Edition”?

JK: I don’t have strong intuitions about marketing or consumer behavior. Truth be told, these Patrician Editions were my business partner’s idea, and I personally feel a bit weird asking people to spend that kind of money on a book. But his instincts are correct and mine aren’t on this. So when he tells me to jump, I jump.

ALIGN: Speaking of Sailer, I may be slow, but I only recently got the "Gone Golfing" reference on those hats you sell. Brilliant! Just copped one in navy.

JK: Maybe we'll do Sailer-themed driver covers next.

ALIGN: Could you describe any mistakes you made or lessons you learned in the course of building up this company?

JK: Most of the things you do running a business, in my experience, anyway, is a mistake in the sense that there was some alternative thing you could’ve done that would’ve been slightly more optimal. It’s a constant process of iterating on your mistakes.

So no, there really isn’t anything I can point to where I’d say “We really screwed that up.” The things that keep me up at night are the little things. I know of about a dozen typos and formatting errors throughout our books that I failed to catch during editing. This drives me crazy. But I’ve come to learn that the vast majority of consumers don’t see these things and trust that when we do make mistakes, we’ll fix them for the next time (and we will).

ALIGN: Any big breakthroughs in the business? Landing a writer or reaching a certain sales milestone?

JK: So far we’ve been very lucky to get exactly the writers we wanted in order to kick off this project. I have to give a special thanks to Curtis Yarvin, who agreed to let me put "Unqualified Reservations" into physical print before I really had a business at all.

That book, which attempted to take Yarvin’s influential blog and convert it to printed media, really was a proof of concept. I didn’t know what I was doing and went through quite a bit of editorial experimentation to figure it out.

The process is not as straightforward as you might think. How do you take a text that is native to the internet — each page containing dozens of hyperlinks (a device central to the writer’s style) and make that accessible to a reader holding the text in his hands as a book?

I encourage you to buy "Unqualified Reservations" to figure out how we pulled it off, but some of the innovations we developed we were later able to apply to the writing of Steve Sailer and Nick Land, both of whom were also gracious enough to give me their business.

ALIGN: To me it’s evident that you have good taste and that anything with the Passage imprimatur is worth checking out.

JK: I agree.

ALIGN: That said, how would you pitch some of your wares to someone going in completely cold? "Noticing," or the Kemp trilogy, or Jünger.

JK: It’s a good question. Where do you start with any of this stuff? I will say that I think it’s all of a piece. Nothing we are publishing is chosen haphazardly. All of this work helps fill out a mental map that, broadly speaking, encompasses what some might call the new right (though I confess I don’t like that term and have my reasons for rejecting it).

In any case, these ideas don’t need to be discovered linearly. One book doesn’t necessarily lead to the next. There is probably a good bit of wisdom in starting with the oldest stuff first, but if I had to offer a suggestion, I’d just say, “Go with your gut.”

ALIGN: What are your plans for the future?

JK: My plans are simple: Keep publishing good, important work that appeals to a broad readership. Disseminate books that can help rebalance our narrative and intellectual foundations so that we can make better decisions both politically and in our own private lives.

ALIGN: What about your own writing?

JK: Unfortunately, my own writing has been put on hold. Maybe one day I will get back to writing fiction, but for now my time and creative energies are best spent servicing the work of others.

ALIGN: Is there a useful name for this “scene” of people building alternative institutions and infrastructure? I never know what to call it when “pitching” to people who aren’t very online. Some shorthand would be useful.

JK: I don’t like labels. To the extent there is a scene, I don’t see it as my job to identify it, lest it becomes too rigid and therefore uninteresting. What this “thing” is, at bottom, is simply a cluster on a social graph, with many overlapping adjacent clusters. Political language like “right,” “dissident right,” “new right,” or whatever doesn’t really belong to us. It’s the language of the people who want to ghettoize what we’re doing, and while I am sympathetic to Conquest’s Law, I would rather not play according to the rules of my enemy’s rhetorical games.

ALIGN: Roughly speaking, I don’t think it’s about an ideology check as much as it is the conscious and public commitment to trusting your own senses and conclusions and any wisdom older than Obama’s second term. People of various political beliefs united by the willingness to realign themselves to proper, true incentives: family, faith, community prosperity, order — human flourishing, basically. As opposed to all the fake incentives DEI etc has installed.

JK: Yes, correct. I’ve described this attitude as “pre-political.” I’m not sure that is a sticky phrase, or even a good one, but I think we should be thinking about our cultural projects outside the frame of politics. They have a political dimension, no doubt, and I’m not trying to suggest that politics don’t matter, or politics are fake or cringe or something, but rather that the creative enterprise, the artistic gesture is derived from more fundamental impulses, more personal impulses, biological and spiritual impulses.