911 calls from deadly Maui fires reveal overwhelmed system, clogged streets, vulnerable seniors

On August 8, 2023, ferocious wildfires wracked the West Maui city of Lahaina, causing residents to panic and reducing many of their beautiful seaside homes to rubble. Blaze News was given copies of hundreds of 911 calls made on or to the island that fateful day, and these calls offer unique and deeply personal insights into what the horrific experience was like for those on the ground.

With 100 people confirmed dead and four still missing, the Maui fires are now considered the worst in modern U.S. history. Thus, as might be expected, the 911 calls made in the midst of the fires paint a grim picture. Through our observations of these calls, Blaze News learned about limited water and human resources dispersed across the island, seniors left abandoned, and streets clogged with vehicles as flames and smoke surrounded them, threatening the people inside.

Blaze News received these calls from Charles Couger, the founder of Blue Tarp Productions and an associate of Blaze Media, who received the calls as the result of a Freedom of Information Act request. Couger requested all 911 calls from 3 p.m. until 5 p.m. on August 8, but he received calls as early as midnight and as late as 5:30 p.m. Blaze News did not receive any 911 calls between the hours of 10 a.m. and 3:30 p.m.

Except in a few instances that Blaze News presumes to have been accidental, officials redacted all caller names and addresses before releasing the calls to protect callers' privacy.

'The whole forest is on fire': The Upcountry Maui fires

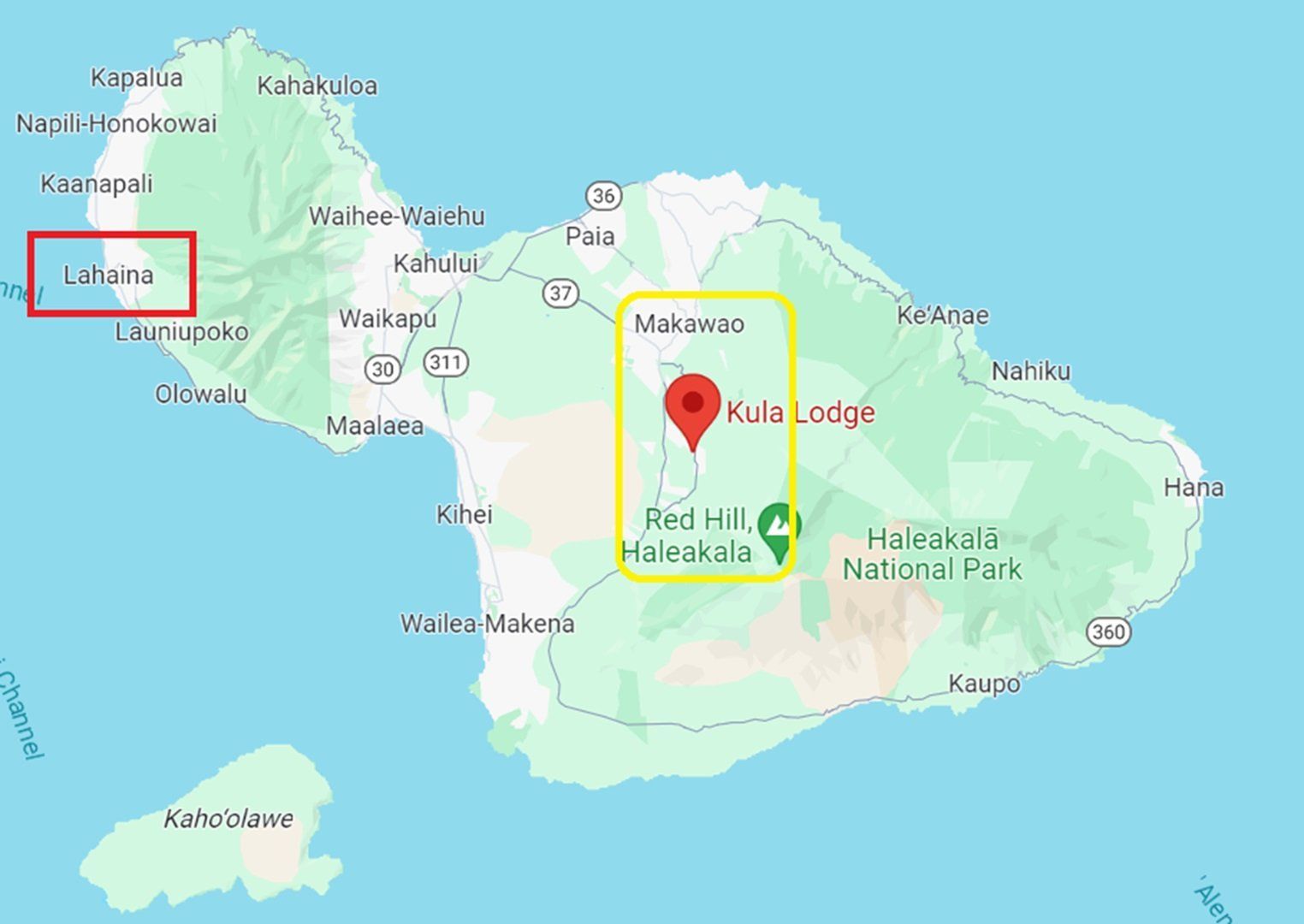

While much of the reporting has focused on the fires in Lahaina, the story of the Maui fires actually begins on another part of the island in an area known as Upcountry. Just before 11 p.m. on August 7, 2023, a surveillance camera at the Maui Bird Conservation Center in the rural Upcountry community of Olinda captured a strange flash, and shortly after midnight on August 8, officials reported a brush fire in that area.

At about the same time, 911 dispatchers began fielding calls about an enormous fire along Olinda Road by the bird sanctuary. This fire and a subsequent fire beneath the Kula Lodge in nearby Kula spread quickly, and together they eventually became known as the Upcountry Maui fires.

At 12:38 a.m., a mother called to relay a terrifying report from her daughter about the fires. "My daughter was trying to go home to the top of Olinda. She just called, freaking out, [saying,] 'The whole forest is on fire, Mom,'" the woman said.

That call came shortly after midnight, in the earliest stages of the fires. By 5:18 p.m. that afternoon, a 911 operator told a concerned resident that the "big fire" she had seen was "below Kula Lodge," confirming that the fires that began more than 17 hours earlier had not abated.

These Upcountry fires were indeed relentless, raging for days and then smoldering for weeks afterward. In all, about 1,000 acres of Kula and the city of Olinda were destroyed.

'The electric went pop': The early-morning fire in Lahaina

The route from Upcountry to Lahaina extends about 40 miles through mountainous terrain, so there is no indication that the Upcountry fires directly led to the fires that eventually broke out in Lahaina. However, Bob Marshall — the CEO of Whisker Labs, which sells in-home devices that detect electrical fires — tells ABC News in the video below that the Lahaina electrical grid became "incredibly stressed" on Monday night and into Tuesday morning, the morning of the Lahaina fires.

At that time, Hurricane Dora also swirled over the ocean south of the Hawaiian Islands, and winds on Maui were especially strong in the days leading up to the fires. Hawaii Gov. Josh Green (D) later claimed some gusts on August 8 reached 81 mph, though others put the number closer to 65 mph. Between the powerful winds and unusually dry conditions, the Lahaina region was especially vulnerable to a fire outbreak.

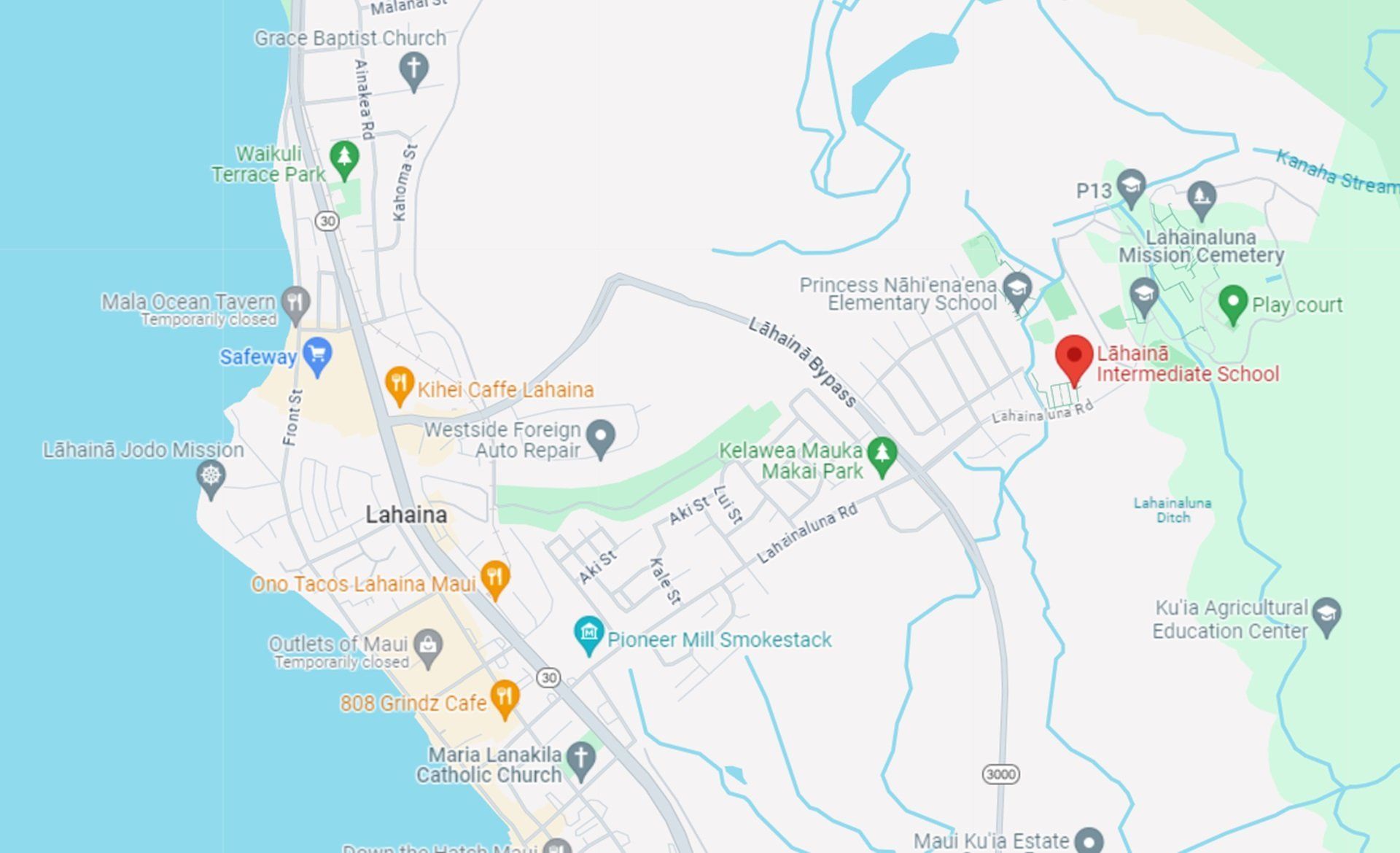

At 6:34 a.m. on August 8, some six hours after the Upcountry fires started, a Lahaina woman called to report a brush fire that began after a "pop" from an electrical unit near Lahaina Intermediate School, located at the intersection of Ho'okahua Street and Lahainaluna Road. "There's a fire by ... Intermediate," she said. "I saw the electric went pop."

Officials later determined that the fire began from a downed power line.

In the next four minutes, 911 received five other calls about the fire at Lahaina Intermediate and the surrounding area along Lahainaluna. Though some of the callers expressed heightened concern as the fire crept nearer and nearer to homes in the neighborhood, this early-morning Lahaina fire apparently remained on the ground, and by 9 a.m., the fire department declared it to be "100 percent contained."

'Someone should have stayed': The early-morning fire reignites

About five or six hours after the fire department declared the early-morning fire in the Lahaina Intermediate School neighborhood to be completely "contained," it flared up once again. Only this time, it spread quickly, growing in size and scope.

Exactly when the fire restarted is difficult to pinpoint, but a recent article from the Hawaii Tribune-Herald provided some clues. The Tribune-Herald claimed that the morning fire was never really extinguished and that it began to burn again almost as soon as "fire crews departed."

"I was angry because they were leaving the area unattended," said 58-year-old Juan Advincula, who witnessed firefighters battle the morning fire. "It was the winds, the dryness, and the embers I was afraid of. Someone should have stayed."

Because Blaze News did not review any 911 calls between 10 a.m. and 3:30 p.m., we could not independently verify that reporting. But whatever the reason for the fire's resurgence, people in Lahaina began calling 911 in the middle of the afternoon on August 8 with truly frightening reports:

- "There's a fire by my condo," said a caller at 3:37 p.m.

- "The electric pole behind our house ... went down. ... And it's dangling," said another a minute later.

- "Smoke [is] everywhere outside my window," a woman reported at 3:46 p.m.

- "It appears that there might be a structure fire, perhaps on the next block up," someone else reported at 3:47 p.m.

Between 3:30 and 4:00 p.m., Maui dispatchers received nearly 40 calls, more than one per minute, though some of these calls related to the Upcountry fires, which still continued to rage.

Because of the Upcountry fires and other emergencies, the Maui County Fire Department and other county officials later defended the decision to dispatch firefighters elsewhere once the early-morning fire was considered "contained." County Fire Chief Brad Ventura noted that at that point, firefighters were needed for "numerous additional calls for service in other parts of West Maui," especially for downed power lines.

The county also issued a news release about a week after the fires, clarifying the difference between "contained" and "extinguished" fires. Contained "means that firefighters have the blaze fully surrounded by a perimeter, inside which it can still burn," the news release said, according to the Tribune-Herald. "A fire is declared ‘extinguished’ when fire personnel believe there is nothing left burning."

The Maui County Fire Department did not respond to Blaze News' request for comment.

'I just had to leave him': Some seniors left to fend for themselves

Perhaps the most heartbreaking calls from the Maui fires involved members of older generations, some of whom were significantly disabled. On multiple occasions, callers reported that elderly residents were trapped in their houses or apartments, with no ability to evacuate the area without help — help that may never have arrived.

A woman from the Hale Mahaolu Eono senior community near Lahainaluna and Kelawea Street called at 3:33 p.m. to say that several residents were still in their units even though community managers left earlier in the day. "My neighbor next door, she's very elderly, and then two doors down, she's 97," the woman said. She also mentioned a 90-year-old woman as well.

During the course of her nine-minute conversation with dispatch — an unusually long call compared to the others made that day — a fire broke out just across the street. "Oh, no, no. We're on fire. F***. ... There's bushes on fire," she exclaimed as fire alarms wailed in the background.

"It's too windy and smoky to go outdoors, and the air is, like, super, super hot," she added.

The woman, who had no car, eventually managed to flag down a stranger to give her a ride, but it does not appear that any of the elderly residents joined her in the car. And sadly, "multiple people" from Hale Mahaolu Eono are listed among the dead, reported the AP, another outlet that accessed copies of the 911 calls via FOIA request.

The residents at Hale Mahaolu Eono were hardly the only Lahaina seniors who were especially vulnerable during the fire. Just three minutes before the Hale Mahaolu Eono call, another woman dialed 911 to report that her uncle was "trapped." Though the caller did not mention the man's age, she did describe him as "handicapped."

"I live on Lahainaluna Road, and our house is right next to the fire, and my uncle is still trapped in the house," she said. "... He's handicapped, and he needs an escort out."

Yet another woman called at about the same time to report that she was forced to leave an aged, incapacitated family member inside his residence so that she could try to save the rest of her family. "He's an 88-year-old man. He cannot transport. He would literally have to be carried out," she explained to the operator. "... I just had to leave him because I have the rest of my family in the car."

The woman informed 911 that the sliding door to the residence was unlocked in the hopes that medics could come to his aid.

About an hour later at 4:29 p.m., as a motorist was speaking with an operator to try to figure out a way out of Lahaina, he interrupted their conversation with an alarming exclamation: "The old folks' home is on fire! The old folks' home is on fire, and there's probably old folks still in there!"

The identity of the "old folks' home" in question is unclear, but according to other callers, it was located across from the Lahaina Surf apartment complex on Waine'e Street, a few blocks from the ocean and nearly two miles west of Lahaina Intermediate School, where the fire first began. According to a dispatcher, the call center received "multiple calls" about that fire.

Twenty minutes after the reports about the fire at the "old folks' home," at 4:49 p.m., a man called to report that he and his wife were unable to evacuate their residence because the wind was too strong for his wife to venture down several flights of stairs. "She walked outside, and the wind almost blew her over, and she can't get down the four flights of stairs," the worried husband said. "So we can't get out of here, and we're surrounded by smoke."

Despite the couple's dire predicament, the operator had few options to offer, as so many first responders had been dispatched to fight the fires. "Where's your neighbors?" the operator wondered. "Do you have anyone around you that can help you?" When the man indicated that the "bunch of girls" nearby were unlikely to be much help, the operator replied, "Well, let me try my best to get a hold of somebody, OK, and try to send them your way."

Less than 10 minutes later, at 4:56 p.m., a man called from outside Lahaina, fretting about his parents who were still in town, as his dad stayed behind, trying in vain to put out the fire that had spread to his house. "My parents are stuck. ... They can't get out," the son began.

"They just called to say, 'I love you. We're not going to make it,'" he added with calm desperation.

Unfortunately, Blaze News was not able to learn whether these callers or their loved ones survived the fires, but the vast majority of those who perished in the fires were older. Of the deceased victims, almost 75% were at least 60 years old and a dozen were at least 80. The oldest victim was 97.

'There's no way out': Severe traffic jams keep people stuck in Lahaina

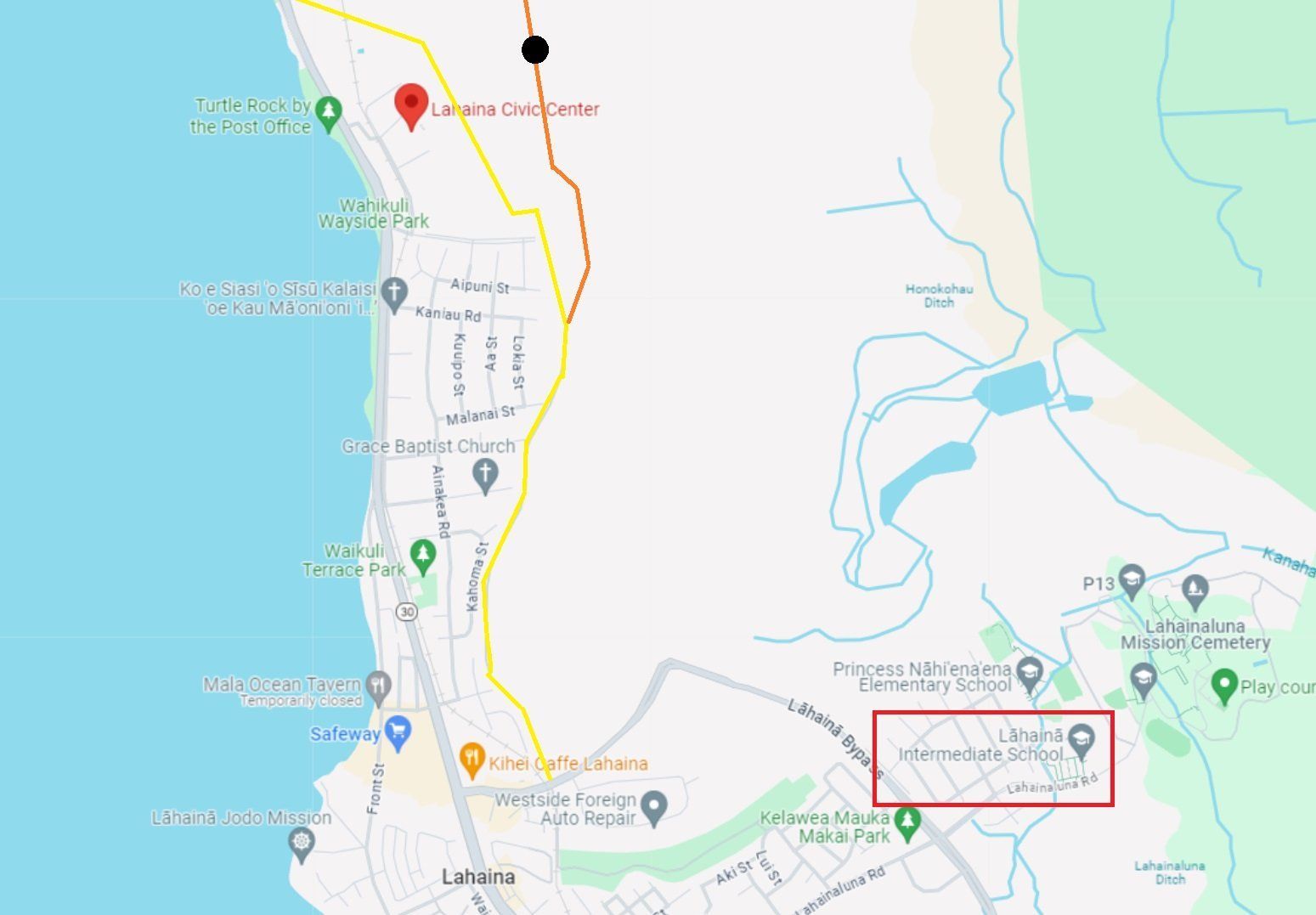

Another common concern for callers was the difficulty in escaping Lahaina by vehicle. By 3:30 p.m., the Lahaina Civic Center had already been set up as a designated shelter for fire refugees, and many people had access to transportation. But major roads like Front Street along the water and Lahainaluna Road, where the early-morning fire started, were soon clogged with cars.

- "Hi, I was just calling to see if there's any policeman directing traffic on Lahainaluna," one caller asked at 4:01 p.m.

- "I'm calling from Front Street, and ... we are stuck here," said another call made at the same time. "... We're wondering if there's any road closures or what's going on."

- "Hi. I'm stuck in the traffic trying to get out of the Kanakea area, and it looks like a house on Kanakea Loop may have caught on fire," said another a minute later. The Kanakea Loop is a neighborhood a few blocks north of Lahainaluna Road.

- "There's no way out, and we're trying to evacuate because the cops previously evacuated, but there is no way out. We're all trapped in the street," a person with a family in the car reported at 4:09 p.m. The family ultimately decided to leave their vehicle and walk.

They weren't the only ones who chose to go by foot rather than by car. As the hours ticked by and gas, cell phone power, and patience began to dwindle, more and more people abandoned their cars and made a run for it, some for the civic center, others for the ocean. Though no one should be criticized for making choices to protect themselves and their families, leaving vehicles in the middle of the street did create an issue for those still hoping to drive away from Lahaina.

One caller described the problem on a call made at 5:30 p.m.: "We don't know where we could go because people are just leaving their cars in the street, and we can't move up."

The dispatcher's response to that caller echoed the responses given to many frustrated drivers anxious to get away from the fire and smoke: Stay the course. "Just stay in your vehicle and be patient with the traffic, OK? There's traffic all over the place, traffic jams, and they're trying to alleviate that right now," the dispatcher said.

Another literal roadblock popped up unexpectedly just as some people thought they had discovered a route to safety. It seems that for a while, first responders were diverting cars onto a dirt road locally referred to as the old cane haul road, as well as to a bike path connected to it. The old cane haul road is located less than a mile inland from the ocean, just behind the Lahaina Civic Center, and runs parallel to Hawaii 30, the main road that follows the western coast of West Maui.

Not only would the old cane haul road have alleviated some of the traffic, but it would have led escapees to the shelter established at the civic center. The plan seemed to work for a while, but according to one woman, "just some guy" who was "not an authority" blocked the route, forcing cars to go back the way they came.

"The guy that closed the gate ... said we cannot go in any more because there's, like, lots of power lines down there," the woman explained to 911 at about 4:50 p.m. "So we go back, but we don't know where to go."

Though that caller never mentioned the old cane haul road specifically, her repeated references to the "dirt road" and her description of a blocked path match a report made by another woman less than five minutes later, at 4:54 p.m. "They routed us straight through on the cane haul road, instead of going down to the main highway [HI 30]," that woman said. "And then now, they shut the gate for everybody to go through, and they put us going back towards the fire."

Someone eventually unlocked the gate, the Honolulu Civil Beat later reported, allowing "several dozen cars" to turn toward the civic center or flee the area. However, others returned to Lahaina and back to the fire. "It’s just sad to even think about," Saman Dias, the chair of a bicycling nonprofit, told the outlet.

Two months after the fires, the Civil Beat openly questioned whether better utilizing the old cane haul road — itself the entry point of what the outlet called "a lesser-known network of private roads" that guide users further inland — could have saved lives that day. Maui County officials have been tight-lipped, with the Joint Information Center telling the outlet that retrospectively questioning the use of the old cane haul road was "irresponsible" during an ongoing investigation into the fires.

'Callous indifference': Electricity continues to flow across Maui

High winds and other conditions had already caused many residences and commercial buildings in Lahaina to lose power before, during, and after the fires, but Hawaiian Electric Co. — which powers 95% of Hawaii, including most of Maui — never shut down its electrical power grid. That decision to keep electricity flowing through the city has led to severe backlash against HECO from critics who claim that electricity exacerbated the wildfire catastrophe.

Such critics point to other fire-prone areas of the U.S., such as parts of California, which have policies in place to shut electricity down pre-emptively when conditions increase the likelihood of fire. Maui, however, has no such protocols.

In a statement issued days after the fires, HECO defended itself for not de-energizing regions of Hawaii during days of exceptionally high winds. The statement indicated that shutting the system down without prior notice would make firefighters' jobs more difficult since Lahaina water pumps require electricity.

Whether the continued flow of electricity contributed to the Lahaina fires has not yet been determined, but HECO currently faces more than a dozen lawsuits that claim the utility company was at least partially responsible for the fires. "To operate Hawaiian Electric’s power lines under these conditions was reckless and represented an abdication of their fiduciary duties and a callous indifference to the loss of human life, tangible property, and natural habitat," one lawsuit read.

HECO did not respond to the Civil Beat's request for comment on the lawsuits.

'I need an ambulance': Other noteworthy events mentioned in the 911 calls

There are a few other events that occurred in Maui on August 8 that, while not directly related to the above topics, are still worth noting.

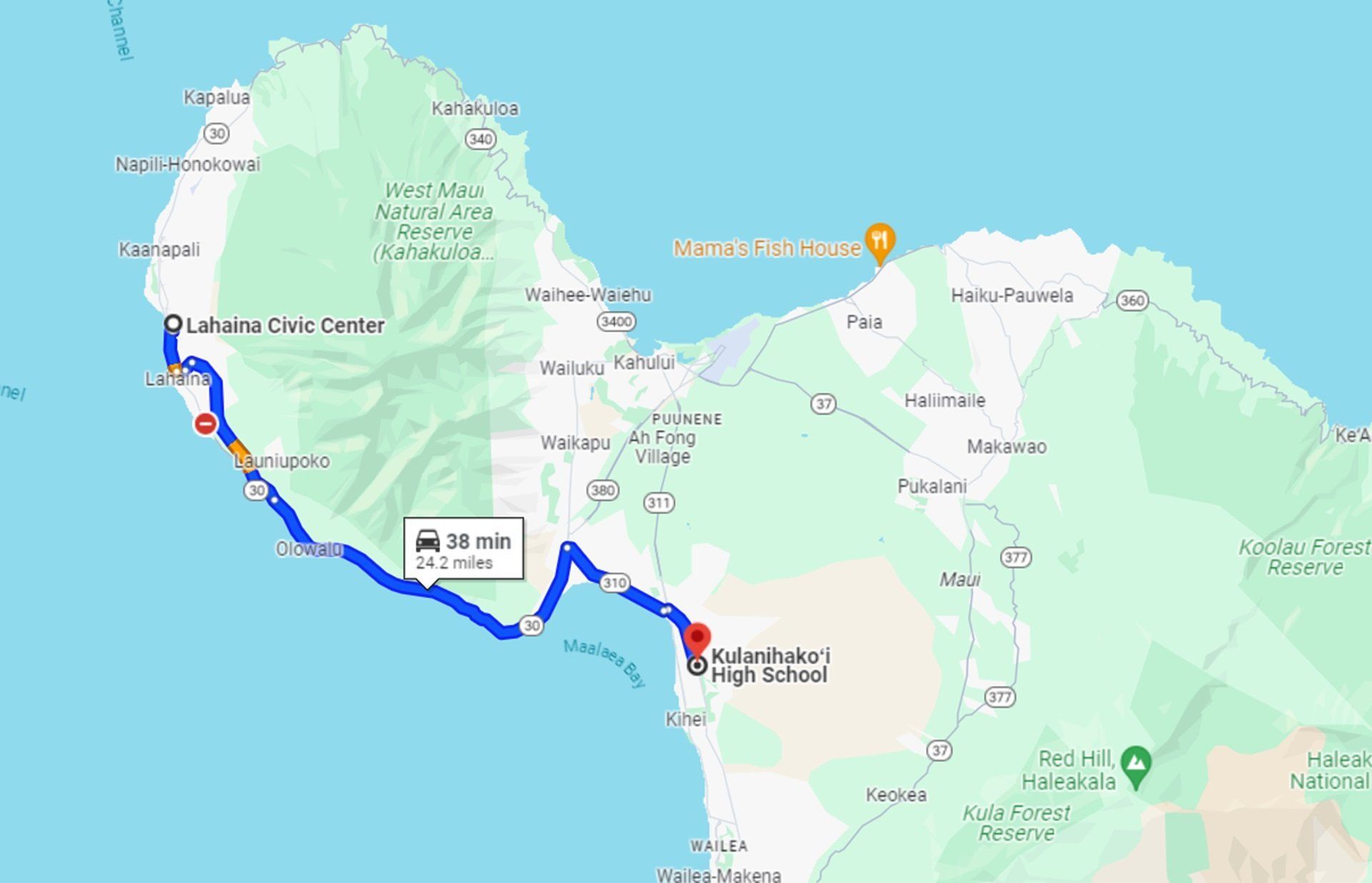

Perhaps most important is the fact that, in addition to the Upcountry fires and the fires in Lahaina, there was yet another fire on the island on August 8. At 6:10 a.m. that day, a fire was reported near a high school in Kihei, located more than 20 miles south of Lahaina.

This fire may have been easily managed, as all calls about it stopped within five minutes or so. However, another fire erupted elsewhere in Kihei on August 9, the day after catastrophe struck Lahaina. Thankfully, the fire in Kihei remained at least 100 yards away from all area residences, Maui Now reported. Still, drone footage captured by Hawaii News Now reveals an extensive burn:

On August 27, CBS News gave an update on all the Maui fires from earlier that month. By that time, Lahaina was 90% contained; Kula and Olinda in Upcountry were 90% and 85% contained, respectively; and Kihei was 100% contained, the outlet said. But the sheer force of these fires and their distance from one another exhausted resources and first responders alike, as water hydrants in Lahaina reportedly began to run dry and just 65 firefighters are typically on duty on the entire island on any given day, the Hawaii Fire Fighters Association estimated.

And, as critical as containing the fires was, not all first responders could give the fires their undivided attention. Police and medics were still needed to perform other vital services, and several 911 calls regarded emergencies that were unrelated to the fires.

"I need an ambulance," one man in Kihei reported at 5:02 p.m. on August 8. "My auntie ... just fell right now." The situation was quite serious, as the man called back 16 minutes later and indicated that his aunt was drifting in and out of consciousness. The dispatcher assured him at the end of that call that an ambulance was on its way.

Another worried father called twice about his son, who had gotten into a moped accident. The father managed to transport his son to a police station but could not find anyone to render the young man medical assistance. Like the woman in Kihei, the man's son seemed to lose consciousness. "Just hang tight, sir," the operator told the father. "... The ambulance is coming right now."

Other calls reported possible criminal behavior, including disorderly conduct and drunk driving. One woman even called to say that her father, who may have previously threatened to kill her family, had stopped by her house and refused to leave.

Finally, Blaze News noticed that later in the afternoon on August 8, beginning around 4:30 or 5 p.m., the 911 operating system no longer operated as smoothly as it had earlier in the day. On a significant number of recorded calls, no caller seemed to be on the line, leaving operators to repeat "hello?" into the void for about 30 precious seconds when time was of the essence.

A few other calls about the fires were somehow misdirected to 911 systems on other islands and had to be transferred to Maui. Maui County encompasses the islands of Lana'i, Moloka'i, Kaho'olawe, and Molokini as well as Maui, so perhaps calls directed from other islands are not unusual. Still, the frequency of such calls seemed to increase later in the afternoon on August 8.

A few 911 calls were also included in the 26-minute Blaze Originals documentary "What Really Happened in Maui?" which features BlazeTV host Lauren Chen and was produced by Charles Couger, the man who furnished Blaze News with the 911 calls. The documentary is available to all BlazeTV subscribers. To become a subscriber, click here. The official trailer for the documentary can be seen below:

What Really Happened in Maui? | Official Trailer

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!

Is Biden Bringing Back Prohibition? | 8/29/23