The Federalist’s Notable Books Of 2025

Seasons greetings! It's time for another exciting and sprawling books recommendation column.

Seasons greetings! It's time for another exciting and sprawling books recommendation column.For more than two centuries, the great American novel has tempted writers who dreamed of capturing the country’s soul between two covers.

From Melville’s "Moby-Dick" to Fitzgerald’s "The Great Gatsby," from Faulkner’s haunted South to Steinbeck’s dust-caked plains, these novels shaped the way Americans saw themselves. Even in decline, the form still attracted giants. Updike, Roth, Morrison — writers who made words shine and sentences sing. Each tried to show what it means to be American: to dream, to stumble, and to start again.

To compound matters, 'Ingram' isn’t just a story of exploration, but also one of self-exploration, in the most literal and least appealing sense.

Now comes comedian, filmmaker, and repentant sex pest Louis C.K. to try his hand at what turns out to be ... a not-great American novel. In truth, it’s awful.

"Ingram" reads like a road map to nowhere — meandering, bloated, and grammatically reckless. The prose wanders as if written under anesthesia. Sentences stretch, then sag. The paragraphs arrive in puddles, not lines. There’s an energy in C.K.’s comedy — a kind of desperate honesty — that, on stage, electrifies. But on the page, that same honesty slips into self-indulgence. The book is less "On the Road" and more off the rails.

To be clear, I love his comedy. I’ve seen him live and will see him again in the new year. He remains one of the most gifted observers of human absurdity alive — a man who can mine a half-eaten slice of pizza for existential truth. But this is not about comedy. This is about writing. And C.K. cannot write. The pacing, the architecture, the restraint — none of it is there.

The story unfolds in a version of rural Texas that seems to exist only in C.K.’s imagination, a land of dull prospects and even duller minds. At its center is Ingram, a poor, half-feral boy raised in poverty and pushed out into the world by a mother who tells him she has nothing left to offer. His education consists of hardship and hearsay. He treats running water like sorcery and basic plumbing like black magic. C.K. calls it “a young drifter’s coming of age in an indifferent world,” but it reads more like rough stand-up notes bound by mistake.

The writing is atrocious. Vast portions of the book read like this:

I couldn’t see my eyes, but I knew what was on my throat was a hand by the way it was warm and tightening and quivering like you could feel the thinking inside each finger, which were so long and thick that one of them pressed hard against the whole side of my face.

Or this:

I sat up, rubbing my aching neck til my breath came back regular, and I crawled out the tent flap myself, finding the world around me lit by the sun, which, just rising, was still low enough in the sky to throw its light down there under the great road, which was once again roaring and shaking above me.

Sentences stretch on like prison terms, suffocated by their own syntax, gasping for punctuation. The dialogue is somehow worse. Ingram’s conversations with the drifters and degenerates he meets on his journey stumble from cliché to confusion, the rhythm of speech giving way to nonsensical babble.

RELATED: Bill Maher and Bill Burr agree Louis CK should be welcomed back in Hollywood

To compound matters, "Ingram," isn’t just a story of exploration, but also one of self-exploration, in the most literal and least appealing sense. There’s a staggering amount of masturbation. C.K. doesn’t so much write about shame as relive it, page after sticky page. His public fall from grace plays out again and again, only now under the pretense of art. It’s less confession than repetition — self-absolution by way of self-abuse, and somehow still not funny.

Any comparisons to writers like Bukowski or Barry Hannah are little more than wishful thinking. Bukowski was grimy, but in a graceful way. He wrote filth with style, turning hangovers into hymns.

Hannah’s madness had a tune to it, strange but unmistakably his own. Even Hunter S. Thompson, at his most incoherent, had velocity. His sentences tore through the page, drug-fueled but deliberate.

C.K.’s writing has none of that. He tries to channel Americana — the heat, the highways, the hard men who dream of escape — but his clumsy prose ensures the only thing channeled is confusion. As C.K. recently told Bill Maher, he did no research for the book, and that much is evident from the first page. His characters talk like they were written by a man who’s only seen Texas through "No Country for Old Men."

In the history of American letters, many great writers have fallen. Hemingway drank himself into oblivion; Mailer stabbed his wife; Capote drowned in his own decadence. But their sentences still stood. Their craft was the redemption. With "Ingram," C.K. has no such refuge. The book exposes the limits of confession as art — that point where self-exposure turns into self-immolation. It could have been great; instead, it’s the very opposite. The only thing it proves is that writing and performing are different callings. Comedy forgives indiscipline. Literature doesn’t.

The great American novel has survived worse assaults — from bored professors, from self-serious minimalists, from MFA factories that mistake verbosity for vision. But rarely has it been dragged so low by someone so convinced of his brilliance. There’s perverse poetry in it, though. A man who was caught with his pants down now delivers a novel that never pulls them back up.

Stephen King got rich by tapping into something universal: the primal, human fears that haunt us all, regardless of race, class, or creed. Books like "The Shining" and "Salem's Lot" are effective whether you read them in Borneo or Bangor, in Czech or Chinese.

Never mind the master of modern horror's recent fixation on America's president — a figure who (at least for King's senescent Woodstock-generation cohort) represents an evil worse than Pennywise and Randall Flagg combined. The author's late-career Trump derangement syndrome can't undo the undeniable impact his more than 60 novels, countless short stories, and a flood of TV and movie adaptations continue to have on pop culture.

King once described organized religion as 'a dangerous tool.' His online tirades often single out Christians, casting them as theocrats, hypocrites, or villains.

That is an impact well-worth examining, especially for Christians. Beneath the lurid gore, King's books can seem oddly comforting and even wholesome. King has a knack for creating heroes out of "regular" Americans, flawed but well-meaning small-town folk who watch "The Price Is Right," drive Chryslers, and buy Cheerios at the supermarket.

What's more, these heroes do battle in a world where good and evil are clearly delimitated, with the former always triumphing over the latter. King seems to adhere to the sort of "culturally" Christian worldview that still held sway in the America of his youth (he was born in 1947).

But a closer look at King's more than 50-year career reveals a consistent tendency to subvert Christianity. Indeed, it seems that King has applied his considerable storytelling gifts to denigrating faith as much as inducing fear.

King doesn’t simply tell tales of terror. He builds worlds where Christianity is a sickness, believers are lunatics, and God is either cruel or indifferent to our suffering. His work isn’t just critical of religion, but a deliberate inversion of it. The sacred becomes sinister, and devotion becomes disease.

In "Carrie," King’s first novel, the villain is not the telekinetic girl but her mother — a wild-eyed Christian who punishes her daughter for being human. Blood becomes sin, the Bible becomes a weapon, and faith is presented as the root of madness. Millions of readers met Christianity through that book and learned to detest the believer more than the devil.

In his novella "The Mist," he repeats the theme. Trapped townsfolk turn to a hysterical woman who quotes scripture on her way to presiding over human sacrifices. She becomes a prophet of panic, a parody of piety. The monsters outside may be frightening, but the believer inside is worse. Once again, King’s message is clear: The sacred is the scariest thing of all.

Then comes 2014's "Revival," perhaps King’s clearest expression of his contempt for Christianity. It begins in a small New England town, where young Jamie Morton meets Reverend Charles Jacobs, a gifted preacher who wins hearts and fills pews. But when tragedy strikes his family, the reverend’s faith vanishes. From his own pulpit, he mocks belief, denounces God, and is driven out in shame.

Years later, Jamie — now a weary musician addicted and adrift — meets Jacobs again, no longer a man of God but a man of wires and obsession. The reverend has replaced prayer with experiments, chasing power instead of purpose. When he finally forces open the door between life and death, what he finds isn’t heaven or hell, but a monstrous parody of creation — an insect god ruling over the void. It’s less revelation than ridicule, King’s way of saying that only a fool would still look to God for guidance.

It’s worth noting what King never touches. He spares Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism the same disdain he reserves for Christianity. To mock those faiths would be called “punching down” by the cultural gatekeepers he aligns himself with.

But his compass is as broken as his conscience — spinning wildly, always pointing away from truth. He pretends he’s striking upward at power when, in truth, he’s sneering downward at the poor and ordinary believers who build churches, not empires. It’s all fair game in art, so long as the victims are mostly white and Christian. Mocking Islam would be “insensitive.” Ridiculing Hinduism would be “problematic.” But tearing into Christianity? That’s considered brave. In King’s moral universe, faith is fair game, as long as it’s practiced in small communities, not gated ones.

Another important point worth emphasizing is that King’s world isn’t godless. Quite the opposite, in fact. It’s god-haunted, but the divine is turned on its head. His priests prey instead of pray. His crosses offer no comfort, only despair.

This is not accidental. King once described organized religion as “a dangerous tool.” His online tirades often single out Christians, casting them as theocrats, hypocrites, or villains. He preaches clarity while painting conviction as madness. The man who once wrote about demons now sees them in ordinary Americans.

What King practices is a kind of spiritual vandalism. He keeps the architecture of Christianity — the rituals, the icons, the language — but fills it with sacrilege. The chalice still shines, but the wine is poison. Grace becomes guilt, creation becomes cruelty, and salvation becomes surrender. It is not atheism but corruption — the gospel rewritten in reverse.

Yet even in his rebellion, King can’t escape the faith he so clearly despises. His stories are soaked in scripture, each one haunted by the very God he denies. Every curse echoes a prayer. Every desecration betrays a longing for what was lost. Behind his hatred lies hunger. A need for meaning, even if that meaning must be mutilated to be felt.

The irony is almost biblical. King writes of hell because he still dreams of heaven. He rejects the transcendent but cannot stop reaching for it. That is why his work feels so spiritual even in its cynicism — because rebellion is, in its way, a strange kind of worship.

This Boomer icon may never kneel before Christ, but his stories do — in rage, not reverence. They curse the altar, yet can’t look away. Stephen King may write about death, but his real subject is the divine he can’t quite kill.

Pick up the "latest" kids’ book these days, and chances are you’ll be met with one or all of the following: a feeble storyline, flat illustrations, and little to no moral value.

Not so, however, when you choose a children’s book by Dr. Matthew Mehan.

'I want the American family to have something beautiful and lasting. I want their witty-wise love of God, country, and family to be helped along, so to speak, by this book.'

In addition to his career as associate dean and associate professor of government at Hillsdale in D.C., Dr. Mehan has built a remarkable reputation as a children’s author. Each of his books is years in the making, and it shows. The finished products are lasting works of art that resonate deeply with readers.

With this in mind, it came as no surprise when Dr. Mehan was awarded one of just five 2025 Innovation Prizes from the Heritage Foundation this summer. The awards are designed to support “innovative projects … that prepare the American public to celebrate our nation’s Semiquincentennial by elevating our founding principles, educating our citizens, and inspiring patriotism.”

Dr. Mehan is putting his prize — as well as a recently awarded NEH grant — toward a collection of fables, tentatively titled "The American Family’s Book of Fables." The book is for all ages, not just kids, and will work through the Declaration of Independence phrase by phrase, supporting and expounding the founding document with an assortment of fables, dialogues, and poems touching on American history, culture, and wildlife.

This week, Dr. Mehan was kind enough to sit down with me to discuss his forthcoming book as well as the history of children’s literature in America.

Faye Root: Could you start by telling me a bit about your background and what inspired you to write children's and family literature?

Matthew Mehan: I've always been interested in creative writing since I was a child. I wrote poetry and short stories, doodled and drew. After college, I published some poems and short stories in a few places.

But I also studied a lot of the great writers, and I noticed they were always practicing the rhetorical arts so that they could be good communicators — be of service. Guys like Cicero, Seneca, Thomas More, Chaucer, Madison, Adams. I started practicing different kinds of writing every night after work, and I started writing these poems about different sorts of imaginary beasts — fables in imitation of Socrates from Plato's "Phaedo." At the very end of his life, Socrates was turning Aesop's Fables into poetic verse.

And that became the seed of my first kids’ book, "Mr. Mehan’s Mildly Amusing Mythical Mammals." I went back for a master's in English and a Ph.D. in literature. I realized I probably needed to find a genre that doesn't expect this kind of literary public service. Children’s literature seemed like a really great place to do this. And then I started having kids as well, and I didn't like what we were doing in the kid lit space.

RELATED: In memory of Charlie Kirk

FR: Couldn’t agree more. My congratulations on your Heritage Foundation Innovation Prize. Your book will be a collection of fables — could you tell me about it?

MM: The book is a direct attempt to celebrate the Semiquincentennial and to teach and reteach the Western tradition and the American principles and people. It's folk stories and traditions: “Here's what it means to be an American. Here's what you should love about America. Here — get to know America.”

It’s divided into 13 parts and works sentence by sentence through the entire Declaration of Independence. Inside each of the 13 sections are three subsections: one for littles, one for middles, and one for bigs. Each of these are tied to an explanation of what that related portion of the Declaration means. The third engine of each of the 13 sections takes you to a different ecological region of the country.

So it's not just the principles of the Semiquincentennial and the Declaration. It's also the people and the stories and the wildlife, the beautiful countryside, and all the animals and creatures God gave us.

The whole book follows one particular funny fellow, Hugh Manatee, who starts in the Everglades, and he transports his heavy bulk by all various manners of technological, very American developments around the entire country.

I wanted a book that a family can engage with no matter their level. And it's designed to be a big heirloom book for the American family to last a long time — 250 years until the 500th anniversary.

FR: Could you talk a bit more about the importance of fables in American history and how the founding generation viewed and used them?

MM: The answer is, they used them just constantly. The fable tradition goes as far back as Solomon, who uses it in the Old Testament. It’s part of our Judeo-Christian, Greco-Roman Western tradition. In fact, kind of a theme of the book is bringing back Roman Republicanism. The beast-fable tradition is very much a part of that self-governing Republican spirit. The founders knew this.

And then you have the fables of the medieval Bestiary, the early moderns, and all the way up to the last major attempt: L'Estrange, whose works were in the library of all the founding fathers. A lot of them also had Caxton. We're talking 1490s and 1700s. So they’re definitely due for an American upgrade.

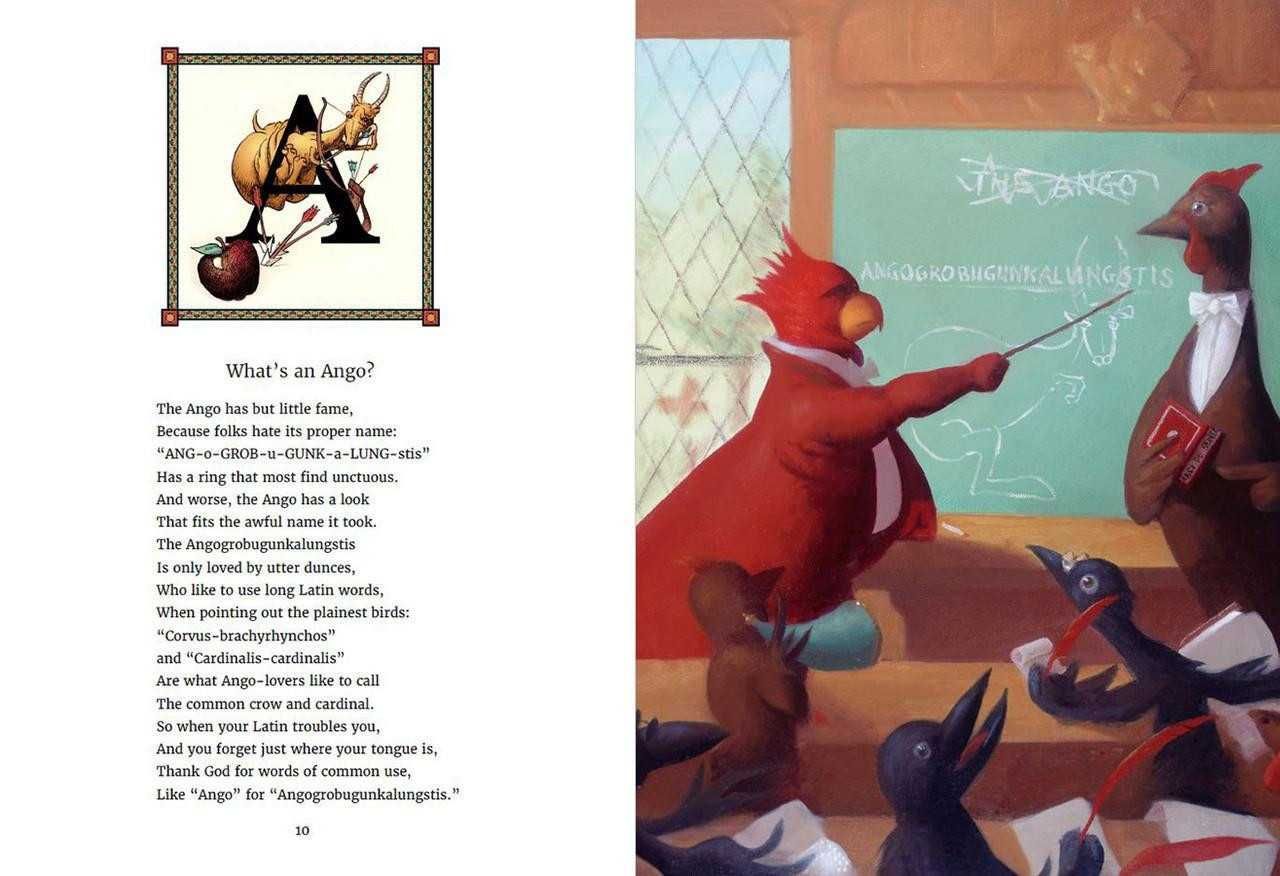

FR: Your book "Mr. Mehan’s Mildly Amusing Mythical Mammals" is an abecedarian. Could you explain what an abecedarian is?

MM: An abecedarian is basically just a fancy word for an ABC book where the structure is not complicated. There’s an A-word, and then some kind of poem or story, a B-word, and then a poem or story, etc.

I did it as a kind of nod to Chaucer, whose first published work of all time was an abecedarian. It was a good, simple structure. I could do the letter blocks for the little people, and each one of the letter blocks had funny alliterative tricks. These and the illustrations were very fun for littles. But then there was higher matter happening, both in some of the poems and the glossary for the adults. So there was sort of deeper matter for adults to seize on to.

For this new book, I've broken it out. I’m being more American, more candid, so it’s clear: This part’s for littles, that part’s for middles, that other part’s for bigs.

FR: In your article “Restoring America's Founding Imagination,” you mention that “children's imaginations were not coddled in our founders’ time.” Could you speak more about that?

MM: Think, for instance, of "Grimms’ Fairy Tales." In these fables, a stepmother might cut off the hands of a child and put stone hands in place, right? "Fancy Nancy" books can't handle that level of violence. But children had to deal with really rough things then. Rough times called them out of their doldrums to attention.

Now, I'm not going to go quite full Brothers Grimm-level gruesome with this book. But there are things, especially in the "Bigs” sections, that go wrong, that are serious. Explorers get burned at the stake. Someone takes an arrow in the sternum. People get shot and killed at Bunker Hill. If you read the school books of the founding period, they're just not messing around. People die because they're foolish, and yes, even kids can die.

You’ve got to be gentle, careful, thoughtful. I try to be measured. But there's got to be ways of introducing these themes to help children be adults. I think a lot of what happens in modern kid lit — why it's not deep, why it's not serious, or rich, or lasting — is because it's so saccharine. It’s not written to call children up to something more.

And you can do that in a very fun, wacky, hilarious, enjoyable way. I try to do that. But I'm trying to mix in that there’s a moral here. It's a different mentality than most of children's books today, but it's much more in keeping with our founding generation and the kind of moral seriousness combined with levity that sustains a witty-wise Republican citizenry. And I think the American audience is really starving for this kind of very moral, witty-wise book.

FR: You emphasize the importance of wit and wisdom in your work. Specifically, why does wit matter, and what role did it play in shaping America’s early identity?

MM: In a certain sense, wit is a virtue. To be witty is to have a certain kind of pleasant humor that can manipulate language, situations — turn them on their head, get people to see something different. And that makes people laugh because mental surprises are actually the source of laughter. Aristotle’s "Nicomachean Ethics" talks about wittiness this way — as playfulness.

Wit also means being "quick" in that sense of being adroit. Adroitness is actually a constituent part of the virtue of prudence — that sort of ability to take a problem and think about it in an adroit or adept way and quickly. That's actually required for prudence.

In fact, the word “wit” in Latin means genius — to grasp something and see: “That's what we should do.” It’s that sort of clever ability to take care of your business, to be able to say, “No, I can handle this. I can think this through. I can puzzle it out. I can come up with a solution. I can invent a new idea.” Think American invention, flight, jazz, computers.

Wit is a creative energy of the imagination and the mind that helps one to rise in this world. Obviously, that has to be wed to principle, to piety, and to the higher things that cannot be compromised, the unchanging things. That marriage of wit and wisdom was something that our founding fathers knew must be done and must be done in each of us.

FR: Finally, could you talk about the illustrations in your upcoming book?

MM: Yes, my dear friend John Folley is a realist impressionist — a classically trained artist. His work mirrors both the realist classical style with some new techniques in Impressionism — particularly playing with light and the heft and weight that light creates.

He makes beautiful oil paintings, which he did for "Mehan’s Mammals." But he also uses a lot of the same principles in watercolor.

For this book, he’s going to do a combination of all of the types of art we've done before. We’ll have 13 major oils that introduce the animals and themes and the ecological areas of the country for each of the 13 parts. And probably one other oil: an American image of wit and wisdom and how Americans ought to pursue it.

And then we’ll have all kinds of pen and ink, computer color, watercolor, a lot of different little images basically populating the rest of the book. It’s going to be a very beautiful, hardback heirloom book. I want the American family to have something beautiful and lasting. I want their witty-wise love of God, country, and family to be helped along, so to speak, by this book.

—

"The American Family’s Book of Fables" is planned for release in May 2026 and will be available everywhere books are sold. Dr. Mehan will follow publication with a national book tour, culminating with the July 4 Semiquincentennial celebrations. For more information, keep an eye on his website.

Also be sure to check out two of Dr. Mehan’s other beloved children’s books: "Mr. Mehan's Mildly Amusing Mythical Mammals" and "The Handsome Little Cygnet."

This interview has been edited for content and clarity.

Christopher Wolfe’s thoughtful essay at the American Mind on Booker T. Washington, leisure, and work stirred some fond memories from years ago of making a friend by reading a book.

He was an old black man, and I was an old white man. We were both native Angelenos and had been just about old enough to drive when the Watts riots broke out in 1965. But that was half a century and a lifetime ago, and we hadn’t known each another.

If you read ‘Up from Slavery,’ you will be reading an American classic and will be getting to know a man who ranks among the greatest Americans of all time.

Los Angeles is a big place, a home to many worlds. Now we were white-haired professors, reading a book together, and we became friends. His name was Kimasi, and he has since gone to a better world.

We were spending a week with a dozen other academics reading Booker T. Washington’s autobiography, “Up from Slavery.” Washington was born a slave in Franklin County, Virginia, just a few years before the Civil War began. He gained his freedom through Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and the Union victory in the war. With heroic determination, he got himself an education and went on to found the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Alabama, where he remained principal for the rest of his life.

After Frederick Douglass died in 1895, Washington became, without comparison, the most well-known and influential black American living. By the beginning of the 20th century, as John Hope Franklin would write, he was “one of the most powerful men in the United States.” “Up from Slavery,” published in 1901, sold 100,000 copies before Washington died in 1915.

It is a great American book. Modern Library ranks it third on its list of the best nonfiction books in the English language of the 20th century. But there was a reason why Kimasi and I were reading this great book when we were old men rather than when we were young men back in the riotous 1960s.

Even before Washington died, and while he was still the most famous and influential black man in America, other black leaders began to discredit him and question his way of dealing with the plight and aspirations of black Americans. These critics, whom Washington sometimes called “the intellectuals,” were led by W.E.B. Du Bois, the first black American to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard and one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

So successful was this criticism that by the time Kimasi and I were in high school or heading off to college, the most fashionable opinion among intellectuals — black or white — was that Booker T. Washington was the worst of things for a black man. He was an “Uncle Tom.” (How “Uncle Tom” became a term of derision rather than the name of a heroic character is a story for another time.) And so, if Washington’s great book was mentioned at all to young Kimasi or me, it was mentioned in this negative light.

But fashions change, and, as Washington himself taught, merit is hard to resist. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and his Second Inaugural Address were dismissed and scoffed at by some “intellectuals” in his day; they are now generally recognized by informed and intelligent people around the world as the great speeches they are.

“Huckleberry Finn” scandalized polite opinion when it came out, because it was about an illiterate vagrant and other lowlifes and contained a lot of ungrammatical talk and bad spelling. A couple of generations later, Ernest Hemingway himself declared that “all modern American literature comes from one book” — Huckleberry Finn.

A couple of generations later still, in our own times, skittish librarians started removing the book from their shelves because it used language too dangerous for children.

The study of the past should shed light on what deserves praise, what deserves blame, and the grounds on which such judgments should be made. Americans being as fallible as the rest of mankind, as long as we are free to air opinions, there will be different opinions among us. Some of them may actually be true. And they will change from time to time, sometimes for good reasons, sometimes for no reason at all.

RELATED: Why can't Americans talk honestly about race? Blame the 'Civil Rights Baby Boomers'

In recent years, several scholars have helped bring back to light the greatness and goodness of Booker T. Washington. Even fashionable opinion is capable of justice, and no one wants to be deceived about what is truly good and great, so I hazard to predict that it will sometime become fashionable again to recognize Booker T. Washington as one of the greatest Americans ever.

Washington never held political office. But his life and work demonstrated that you don’t have to hold political office to be a statesman and that the noblest work of the statesman is to teach. The soul of what Washington sought to teach was that we, too, can rise up from slavery. It is an eternal possibility.

This was the central purpose of Booker T. Washington’s life and work: to liberate souls from enslavement to ignorance, prejudice, and degrading passions, the kind of slavery that makes us tyrants to those around us in the world we live in.

Washington saw that this freedom of the soul cannot be given to us by others. Good teachers and good parents and friends, through precept and example, can help us see this freedom and understand it, but we have to achieve it for ourselves. When we do, our souls are liberated to rule themselves by reflection and choice, with malice toward none, with charity for all.

If you read “Up from Slavery,” you will be reading an American classic. You will be getting to know a man who, in the quality of his mind and character, and in the significance of what he did in and with his life, ranks among the greatest Americans of all time — even with the man whose name he chose for himself. When we read this great book together in the ripeness of our years, Kimasi, who always winningly wore his heart on his sleeve, wept frequently and repeated, shaking his head, “I lived a life not knowing this man.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published at the American Mind.