![]()

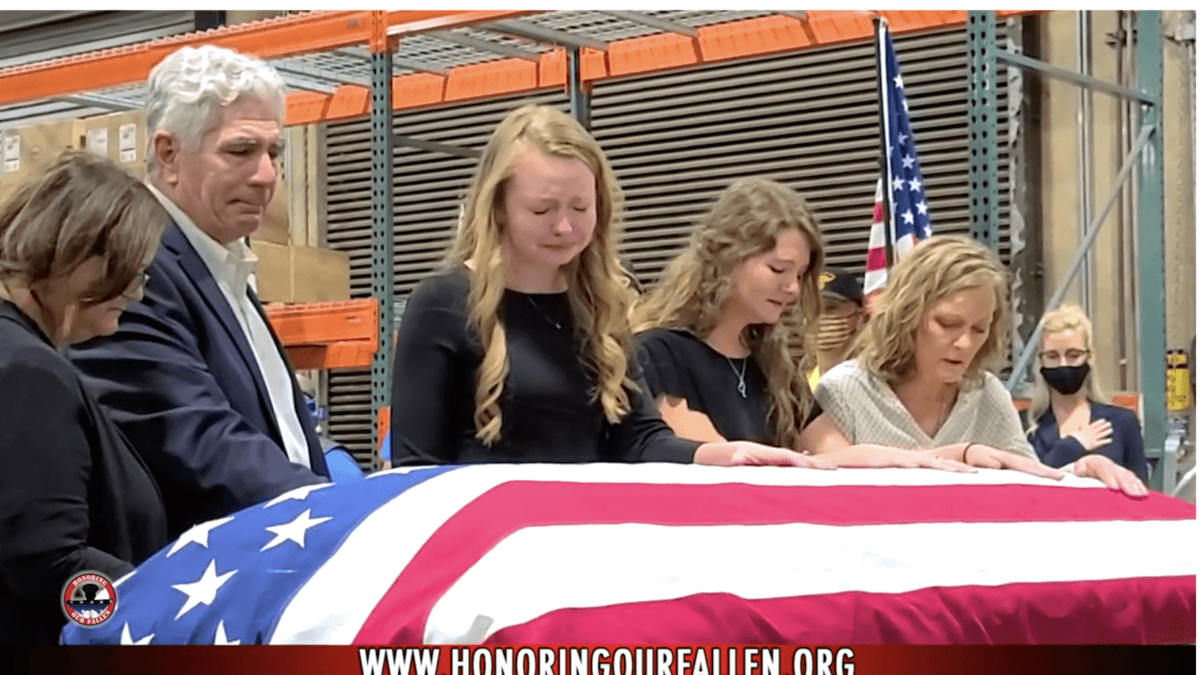

Since the commencement of Operation Epic Fury, six United States service members have been killed in the Middle East. Four of the six have now been identified.

On Tuesday, the Department of War released the identities of four Army Reserve soldiers who died on Sunday in support of the operation against Iran.

'We will remember their names, their service, and their sacrifice.'

The soldiers died in Kuwait at the Port of Shuaiba during an unmanned aircraft system attack, according to the U.S. Army's press release. All four were assigned to the 103rd Sustainment Command, Des Moines, Iowa.

RELATED: US service member death toll continues to rise amid Operation Epic Fury

The deceased were identified as: Capt. Cody Khork, 35, of Lakeland, Florida; Sgt. 1st Class Nicole Amor, 39, of White Bear Lake, Minnesota; Sgt. 1st Class Noah Tietjens, 42, of Bellevue, Nebraska; and Sgt. Declan Coady, 20, of Des Moines, Iowa.

“We honor our fallen Heroes, who served fearlessly and selflessly in defense of our nation. Their sacrifice, and the sacrifices of their families, will never be forgotten,” said Lt. Gen. Robert Harter, chief of Army Reserve and commanding general U.S. Army Reserve Command.

“On behalf of the Army Reserve, we express our heartfelt condolences to their families and loved ones. We remain steadfast in our commitment to honoring the legacy of our fallen and supporting their teammates and families during this difficult time,” said Harter.

“Our nation is kept safe by folks like these — brave men and women who put it all on the line every single day. They represent the heart of America. We will remember their names, their service, and their sacrifice," said Maj. Gen. Todd Erskine, commanding general, 79th Theater Sustainment Command.

ABC News reported that the other two service members' identities are being withheld until after next of kin have been notified. They were reportedly killed in the same strike. Eighteen others were reportedly injured in the strike as well.

The incident is currently under investigation.

![]() Capt. Cody Khork, a resident of Lakeland, Fla., enlisted as a 13P, Multiple Launch Rocket System/fire direction specialist in the National Guard in 2009. He commissioned as a military police officer in the Army Reserve in 2014. He deployed to Saudi Arabia in 2018; Guantanamo Bay, Cuba in 2021; and Poland in 2024. U.S. Army

Capt. Cody Khork, a resident of Lakeland, Fla., enlisted as a 13P, Multiple Launch Rocket System/fire direction specialist in the National Guard in 2009. He commissioned as a military police officer in the Army Reserve in 2014. He deployed to Saudi Arabia in 2018; Guantanamo Bay, Cuba in 2021; and Poland in 2024. U.S. Army

![]() Sgt. 1st Class Nicole Amor, a resident of White Bear Lake, Minnesota, enlisted in the National Guard as a 92A, automated logistics specialist in 2005. She transferred to the Army Reserve in 2006 and deployed to Kuwait and Iraq in 2019. U.S. Army

Sgt. 1st Class Nicole Amor, a resident of White Bear Lake, Minnesota, enlisted in the National Guard as a 92A, automated logistics specialist in 2005. She transferred to the Army Reserve in 2006 and deployed to Kuwait and Iraq in 2019. U.S. Army

![]() Sgt. 1st Class Noah Tietjens, a resident of Bellevue, Nebraska, enlisted in the Army Reserve in 2006 as a 91B, wheeled vehicle mechanic. He had two deployments to Kuwait in 2009 and 2019. U.S. Army

Sgt. 1st Class Noah Tietjens, a resident of Bellevue, Nebraska, enlisted in the Army Reserve in 2006 as a 91B, wheeled vehicle mechanic. He had two deployments to Kuwait in 2009 and 2019. U.S. Army

![]() Sgt. Declan Coady, posthumously promoted from specialist, a resident of Des Moines, Iowa, enlisted in the Army Reserve in 2023 as a 25B, Army information technology specialist. U.S. Army

Sgt. Declan Coady, posthumously promoted from specialist, a resident of Des Moines, Iowa, enlisted in the Army Reserve in 2023 as a 25B, Army information technology specialist. U.S. Army

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!

How many more families will have to hear the death knell of the doorbell? At the very least, they should know what it is we’re fighting for.

How many more families will have to hear the death knell of the doorbell? At the very least, they should know what it is we’re fighting for.

Capt. Cody Khork, a resident of Lakeland, Fla., enlisted as a 13P, Multiple Launch Rocket System/fire direction specialist in the National Guard in 2009. He commissioned as a military police officer in the Army Reserve in 2014. He deployed to Saudi Arabia in 2018; Guantanamo Bay, Cuba in 2021; and Poland in 2024. U.S. Army

Capt. Cody Khork, a resident of Lakeland, Fla., enlisted as a 13P, Multiple Launch Rocket System/fire direction specialist in the National Guard in 2009. He commissioned as a military police officer in the Army Reserve in 2014. He deployed to Saudi Arabia in 2018; Guantanamo Bay, Cuba in 2021; and Poland in 2024. U.S. Army Sgt. 1st Class Nicole Amor, a resident of White Bear Lake, Minnesota, enlisted in the National Guard as a 92A, automated logistics specialist in 2005. She transferred to the Army Reserve in 2006 and deployed to Kuwait and Iraq in 2019. U.S. Army

Sgt. 1st Class Nicole Amor, a resident of White Bear Lake, Minnesota, enlisted in the National Guard as a 92A, automated logistics specialist in 2005. She transferred to the Army Reserve in 2006 and deployed to Kuwait and Iraq in 2019. U.S. Army Sgt. 1st Class Noah Tietjens, a resident of Bellevue, Nebraska, enlisted in the Army Reserve in 2006 as a 91B, wheeled vehicle mechanic. He had two deployments to Kuwait in 2009 and 2019. U.S. Army

Sgt. 1st Class Noah Tietjens, a resident of Bellevue, Nebraska, enlisted in the Army Reserve in 2006 as a 91B, wheeled vehicle mechanic. He had two deployments to Kuwait in 2009 and 2019. U.S. Army Sgt. Declan Coady, posthumously promoted from specialist, a resident of Des Moines, Iowa, enlisted in the Army Reserve in 2023 as a 25B, Army information technology specialist. U.S. Army

Sgt. Declan Coady, posthumously promoted from specialist, a resident of Des Moines, Iowa, enlisted in the Army Reserve in 2023 as a 25B, Army information technology specialist. U.S. Army

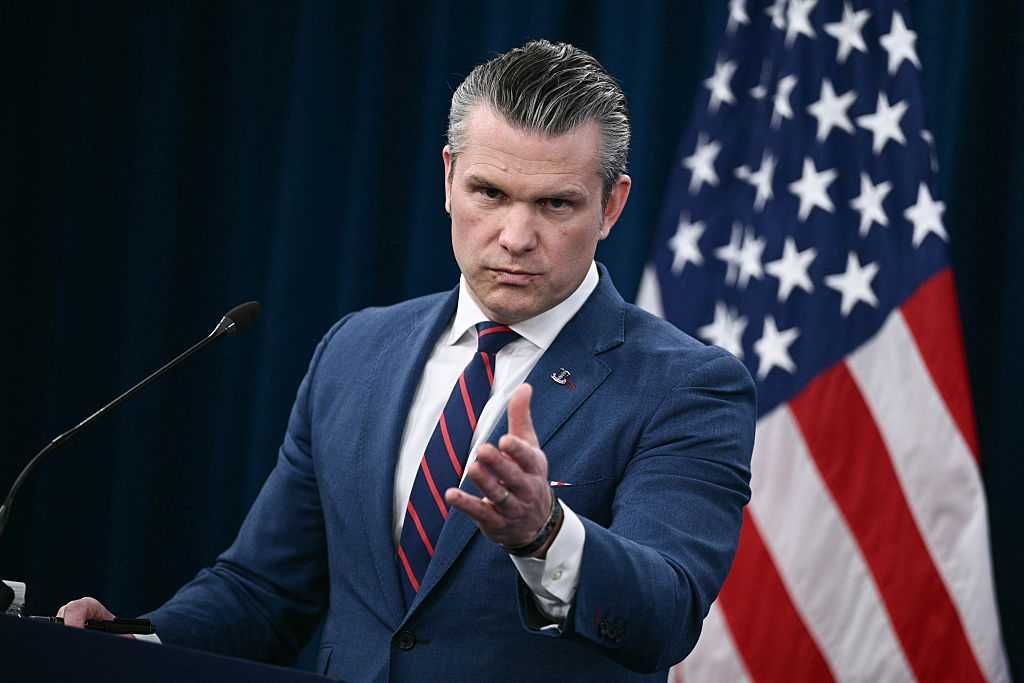

Photo by Brendan SMIALOWSKI / AFP via Getty Images

Photo by Brendan SMIALOWSKI / AFP via Getty Images Photo by Brendan SMIALOWSKI / AFP via Getty Images

Photo by Brendan SMIALOWSKI / AFP via Getty Images

Drugs seized in the joint operation carried out since January of last year. U.S. Embassy of Ecuador

Drugs seized in the joint operation carried out since January of last year. U.S. Embassy of Ecuador