![]()

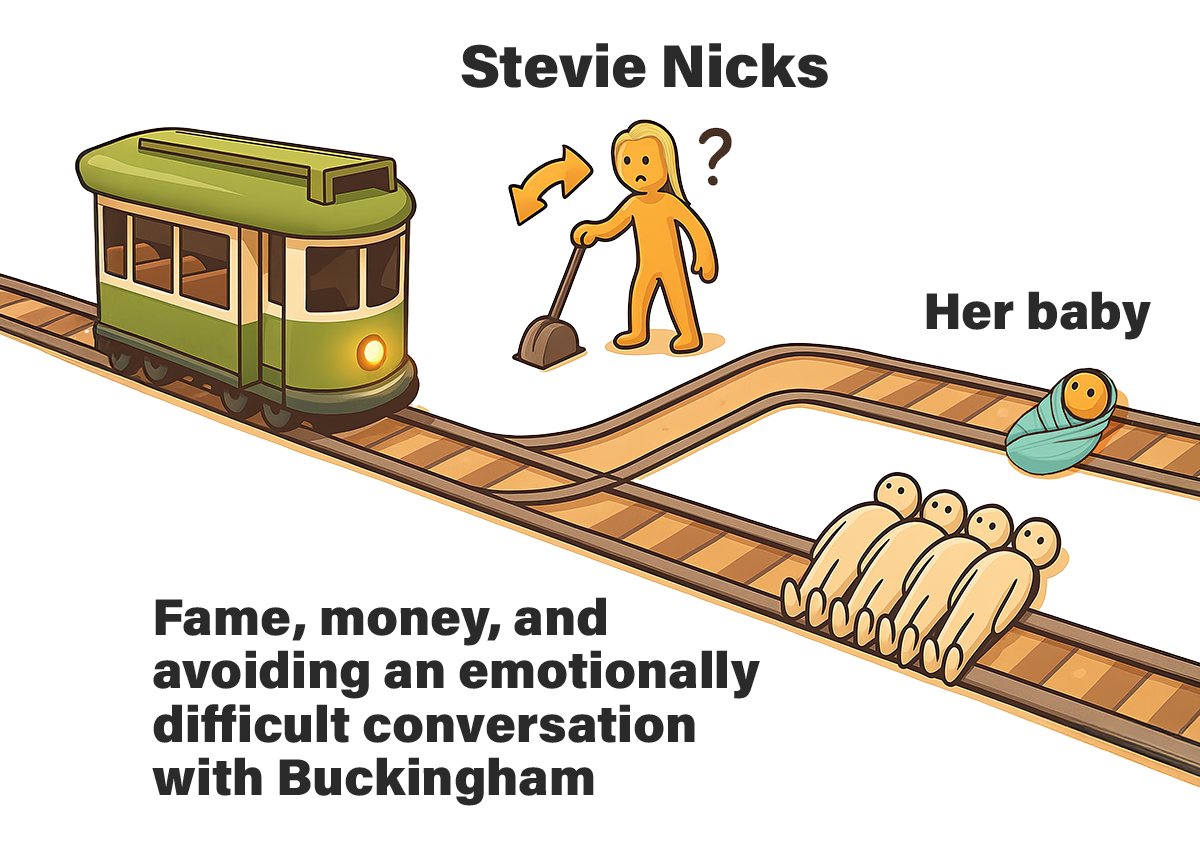

My daughter is 7 years old. She is adorable, kindhearted, and full of life. I would do anything to protect her.

Now think about all the 7-year-olds in your life — children, nephews, nieces, neighbor kids. Statistically speaking, 50% of them will be exposed to pornography in the next five years. Read this paragraph repeatedly until the gravity of it hits you.

Family is the building block of society, and pornography is the corrosive acid that is eating away at its foundation.

As bad as a Playboy would be, I am not talking about a magazine. I am talking about the most depraved, hard-core, and often violent sexual intercourse footage ever conceived in the human mind that is available with a few clicks to anyone with access to a smartphone or computer. The median age of first exposure to this content is 12 years old; 15% will view hard-core pornography before they graduate elementary school.

As Florida Attorney General James Uthmeier is finding out, age verification checks are doing little to deter any of this and are as easy to pass through as our border during the Biden administration.

What kind of sick society allows this?

Pornography's effects

Pornography is a corrosive acid that rots the soul; steals innocence; destroys marriages; fuels objectification, exploitation, and sex trafficking of women and children; increases rape and abuse rates; and unravels the moral fabric of society, causing great public harm. It increases anxiety, shame, sexual dysfunction, and relationship unhappiness among those who use it.

As J.C. Ryle said well, “Nothing darkens the mind so much as sin; it is the cloud which hides the face of God from us.”

Porn use affects every part of our mind, body, and soul. It inflicts immense external harms on individuals and society.

Not only does it directly warp the minds of America’s children, it affects them in indirect ways. Recent data indicates that marriages in which at least one spouse views pornography are nearly twice as likely to result in divorce, and the effects of divorce on children are staggering. Children of divorced parents often experience heightened levels of anxiety, depression, and behavioral issues.

A study by the University of Illinois Chicago indicates that divorce may lead to social withdrawal, attachment difficulties, and increased behavioral problems in children.

RELATED: Pornography is a threat to families — and to civilization

![]() Valentina Shilkina/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Valentina Shilkina/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Research published in the Journal of Divorce & Remarriage found that children from divorced families are more likely to exhibit lower academic performance compared to their peers from intact families. Data from PLOS One indicates that individuals who experienced parental divorce before the age of 18 have a 61% higher risk of experiencing a stroke in adulthood. Research from Baylor University indicates that adults who experienced parental divorce during childhood have lower levels of oxytocin, a hormone associated with relationship bonding and emotional regulation.

Family is the building block of society, and pornography is the corrosive acid that is eating away at its foundation. Without any redeeming element whatsoever, pornography destroys marriages, destroys lives, and steals the innocence and protection of the young.

All of these outcomes are the result of a choice made by public officials who refuse to stand in the way of this obscene content being published.

What kind of sick society allows this?

What about the First Amendment?

Pornography is not “speech” in any meaningful, constitutionally protected sense. We rightly prohibit prostitution. Yet somehow, when the same act is filmed and distributed to millions of people over the internet, prostitution becomes exalted as “protected speech.”

This is legal nonsense of the highest order. It insults the intelligence of the American people and is a crime against children and the moral fabric of any society. To claim that the founding fathers fought and bled to secure a right to broadcast prostitution is as absurd as it is evil.

No serious person believes this legal framework is the result of honest lawmaking or faithful judicial interpretation. Rather, this perverse outcome is a product of cultural rot and late 20th-century judicial activism. Our courts were captured by ideologues more committed to preserving the sexual revolution at any cost than upholding constitutional fidelity.

But common-law tradition and Supreme Court precedent provide a clear path to prohibition.

Justice William Rehnquist, writing for the Supreme Court in Barnes v. Glen Theatre (1991), rightly noted that public nudity was a criminal offense at common law. The founders did not interpret the First Amendment as a shield for public obscenity, indecency, or exhibitionism. In fact, Miller v. California (1973) gives us the legal test we need: If material appeals to the prurient interest, depicts sexual conduct in a patently offensive way as defined by contemporary standards, and lacks serious political, educational, or artistic value, it is not protected by the First Amendment.

Modern pornography clearly meets all three criteria — except where legislatures have failed to define and prohibit it accordingly.

RELATED: Porn has transformed into horror

![]() DNY59/iStock/Getty Images Plus

DNY59/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Pornography’s advocates point to Reno v. ACLU (1997), but the ruling was based on the failure of the bill in question to distinguish “obscene” from “indecent.” Moreover, the court justified its decision by claiming the internet was less invasive than radio or television.

How well does that assertion hold up 28 years later?

The internet is now the primary battleground for the soul of this generation. Because of its incorrect factual findings and clear disregard for the power clearly reserved to the states, any element of Reno and other opinions that would prohibit states and municipalities from banning public obscenity should be overturned. There are upcoming opportunities to do so. State legislatures need to provide more.

It is past time for us to recognize that publishing prostitution footage is not speech — it is an attack on human decency and the moral fabric necessary to hold families and the republic together. We must deal with it as such.

That is why I filed SB593 to abolish pornography in Oklahoma.

What SB593 does

SB593 would define “obscenity” according to the Miller test and outlaw the production, distribution, sale, and possession of obscene pornography in Oklahoma. It would re-establish the state’s authority to prosecute those who profit from the destruction of marriage, innocence, and society. It would empower law enforcement to shut down pornography rings that exploit women and children. It also increases penalties for child pornography.

The American people — many suffering the effects of a culture drowning in pornographic material — are increasingly supportive of bills like this one.

A society without pornography is better than one with it.

A 2024 YouGov poll found that support for and opposition to the total pornography ban suggested by Project 2025 were split evenly at 42-42. Among Republican voters, 60% were in support, with only 27% opposed. Republican officials can ban pornography, knowing their voters have their back by a greater than two-to-one margin.

Many object that the bill, or others like it, will be challenged in court, but that is no reason to shrink back. The goal is to pass the bill, but not merely that — it is also to force a reckoning. The Miller test provides a well-established framework to ban obscene pornography. The factual findings from Reno have been proven disastrously wrong.

Public opposition to pornography is rising. There is no better time to put this discussion before the American people and the Supreme Court.

Time to act

The left possesses no limiting principle to forcing its twisted, Marxist vision of the good on society. Leftists weaponize agencies to perform raids on political opponents, meme-makers, and pro-life protesters. They collude with social media companies to censor right-leaning opinions. They shut down businesses and churches.

Yet too many on the right still flinch at any minor deviation from utter libertinism.

A society without pornography is better than one with it. Everyone knows this, yet too many cling to unlimited, laissez-faire state approval of public prostitution footage. People have been conditioned to believe that the highest conservative principle is inaction and “neutrality.”

It is children who pay the biggest price for this folly.

Pornography exemplifies this crisis: It objectifies people made as God’s image-bearers, reducing them to commodities for gratification, thus defacing the imago Dei and alienating us from our creator. Neurologically and spiritually, it rewires the brain's reward pathways, creating addictive filters that pervert sexual perception and fracture body-soul unity, as Jesus warns in Matthew 5:28.

This echoes broader anthropological harms, fueling exploitation, addiction, and societal division that undermine human flourishing and the common good.

In legislating against it, we affirm God's design for humanity. This is not about criminalizing private lustful thoughts (a sin for the church) but addressing external actions that exploit, addict, and divide (a crime for the state). By enacting such a law, we honor God, protect the vulnerable, and fulfill our duty to promote the common good.

What kind of sick society allows pornography?

For the sake of children and the survival of the republic, pornography must be abolished.

Photo by Bildagentur-online/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Photo by Bildagentur-online/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Lisa Haney via iStock/Getty Images

Lisa Haney via iStock/Getty Images There’s room between ceding ground to the left that need not be ceded and pretending like the decades-long campaign to alienate and ostracize conservatives is not pushing some people into dark corners.

There’s room between ceding ground to the left that need not be ceded and pretending like the decades-long campaign to alienate and ostracize conservatives is not pushing some people into dark corners.

Photo by Tommaso Boddi/Getty Images for UCLA Jonsson Cancer Center Foundation

Photo by Tommaso Boddi/Getty Images for UCLA Jonsson Cancer Center Foundation

Honor Charlie's legacy by asking yourself each day, 'How can I demonstrate the type of moral courage that he displayed to the very end?'

Honor Charlie's legacy by asking yourself each day, 'How can I demonstrate the type of moral courage that he displayed to the very end?' Demanding, as Douglas Wilson seems to do, that public officials proclaim their personal faith in Christ is neither wise, nor moral, nor American, nor Christian.

Demanding, as Douglas Wilson seems to do, that public officials proclaim their personal faith in Christ is neither wise, nor moral, nor American, nor Christian.

Valentina Shilkina/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Valentina Shilkina/iStock/Getty Images Plus DNY59/iStock/Getty Images Plus

DNY59/iStock/Getty Images Plus