Carjacker abandons infant on sidewalk — but Good Samaritan having a frustrating day ends up in the perfect spot to help

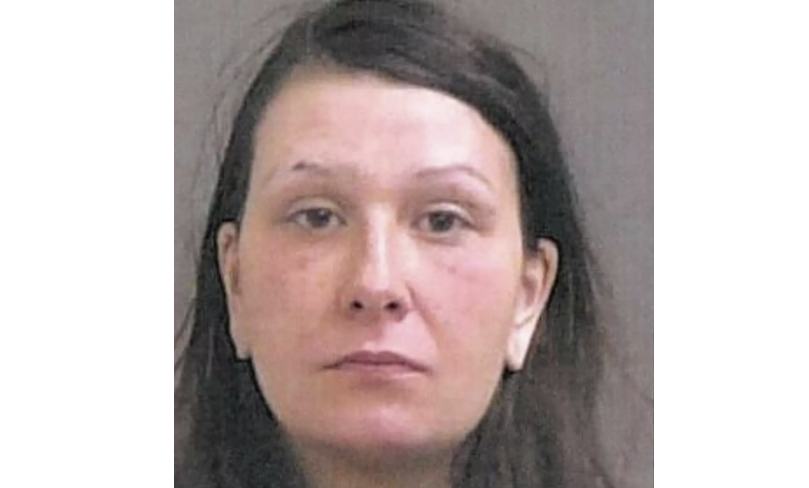

A real-life nightmare took place July 3 in Chicago when authorities said a 15-time convicted felon named Jeremy Ochoa carjacked an SUV, allegedly dragged the female motorist, and drove off with the victim's 7-month-old daughter still strapped inside the vehicle, CWB Chicago reported.

Police tracked the stolen 2011 GMC Acadia using license plate reader alerts and pings from a cell phone that had been left inside the vehicle, the outlet said, adding that cops eventually found the SUV several miles southeast of the scene of the carjacking. But the vehicle was unoccupied.

'I just kept praying.'

So where was the baby?

That same day, Earl Abernathy was sitting in traffic on his way to work, WBBM-TV said. Plus, he was dealing with non-operational air conditioning in his car as temperatures hit the 90s — so he was forced to keep his windows down, WBBM said.

Amid those frustrations, along with getting an earful of all the street noise amid Chicago's unforgiving summer heat, an unnerving sound caught Abernathy's ear.

It was a baby crying.

Abernathy told WBBM he put his hazard lights on, got out of his vehicle, and ran over to the infant, who was all alone in a car seat.

Prosecutors told CWB Chicago that the baby was found "abandoned on the sidewalk."

Police said Ochoa — the accused carjacker — had gotten rid of the baby who had been strapped in the stolen SUV and left her in front of St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church in the 800 block of West Roosevelt Road, which is about four miles from the BP gas station where the carjacking went down, WBBM noted.

After coming to the infant's rescue, Abernathy called 911 and even went on Facebook Live to see if anyone could identify her, WBBM said.

"I just feel like that's what a normal person would do," Abernathy added to WBBM. "I just felt like it was just a bogus situation. Everybody I saw was riding past."

As you might expect, the little girl's family was heavy on the hunt for her.

"We were panicking. We panicked," the baby's grandmother, Karen Fuller, later told WBBM. "We didn't know, and I just kept praying."

Fuller added to WBBM that she's grateful that Abernathy got out of his car to help her 7-month-old granddaughter, who was soon reunited with family, was unharmed, and has been doing well.

"I was so happy," Fuller noted to WBBM. "I went to his page, and I thanked him so many times."

Abernathy told WBBM he wouldn't hesitate to do it all over again: "Of course, any time. It could have ended differently. I'm just glad it ended the way it ended."

As for Ochoa, CWB Chicago said he was arrested just before noon — less than two hours after the carjacking — and was charged with aggravated vehicular hijacking of a vehicle with a passenger under 16 and aggravated kidnapping of a child. Cook County Jail information accessed Friday morning indicates the 39-year-old's next court date is July 29.

Observers very well may say Abernathy — the Good Samaritan in this otherwise nightmarish situation — may not have been able to help in the place and time he did had he not been stuck in traffic and forced to endure blistering heat with his windows down, given his lack of A/C. Indeed, it might be said that his frustrating circumstances seem to have come together to allow a heroic outcome — in front of a church, no less.

Steve Deace — BlazeTV host of the “Steve Deace Show” and a columnist for Blaze News — had the following to say about the turn of events.

"This heroic story is like a metaphor for the era — and what it is lacking," Deace told Blaze News. "An actual man took action that saved innocent life, and he was compelled to by inconvenience. We have too few men, too many conveniences."

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!