Why Sex And The City Could Never Be A Fairy Tale

Sex and the City feminism sees living like a bad man as the key to empowering women to live the good life.

Sex and the City feminism sees living like a bad man as the key to empowering women to live the good life.A new DC Cinematic Universe has taken flight with James Gunn’s “Superman.”

While critics from both sides of the political aisle argue over whether the film is “woke” (it’s not), I want to highlight a more meaningful — and largely overlooked — message at the heart of the story: the power of kindness in a cynical, chronically online world. Based on the knee-jerk backlash the movie has inspired online, it’s a message we clearly need.

Some have called this version of Superman ‘weak,’ but I see something else — something that’s been missing from many past iterations: humanity.

While this “Superman” couldn’t be more timely — it explores themes of individuality, idealism in the face of public scrutiny, cancel culture, and life in a social media-saturated society — it ultimately uses these themes to emphasize the timeless traits that have allowed the character to endure for almost a century.

“Superman” centers on a younger Clark Kent (David Corenswet), who has been active as Superman for just three years. While beloved by many, others see him as a wild card and potential threat — especially after he intervenes in a war between two fictional nations, Boravia and Jarhanpur.

Superman protects the defenseless people of Jarhanpur from Boravian forces, but his actions anger the U.S. government, which fears conflict with Boravian allies. Lex Luthor (Nicholas Hoult) seizes the moment, convincing the military to back his surveillance program, “Planet Watch,” as a pretext to go after Superman. He even unleashes a swarm of mind-controlled monkeys to flood the internet with anti-Superman propaganda — #supers**t trending like wildfire.

Meanwhile, Clark’s girlfriend and Daily Planet reporter Lois Lane (Rachel Brosnahan), who knows his true identity, challenges him to explain his actions in a professional interview. It’s a complicated, very modern kind of pressure.

What makes this Superman compelling is that he’s not driven by politics or power — he just wants to help people. All people. He doesn’t weigh the geopolitical consequences; he sees someone in danger and acts. That impulse, that moral clarity, is what defines him. It’s also what gets him into trouble.

This instinct is rooted in a message from his Kryptonian parents — a message that, when finally decrypted by Luthor, reveals their true plan: They hoped their son would one day rule Earth and repopulate it with Kryptonians. Even Superman didn’t know this. Suddenly, even his most selfless actions come under suspicion.

RELATED: Superman's message to MAGA: ‘You’re not American’ if you don’t love immigrants

Some have called this version of Superman “weak,” but I see something else — something that’s been missing from many past iterations: humanity. He’s not a flawless, all-powerful icon. He’s relatable. Grounded. Fallible. And when the world turns on him, his powers offer no protection from the sting of media outrage or public mistrust. Stripped of certainty, he holds fast to one thing: hope. Hope for a kinder world.

That perseverance — trying to do good even when it’s hard or unpopular — feels deeply human. Isn’t that what we all wrestle with? We want to be seen, to be understood, to be forgiven when we mess up. Especially in the age of cancellation, when any misstep is dissected in real time by a million strangers. Superman, in that sense, becomes a stand-in for anyone who’s tried to do the right thing and gotten burned for it.

There’s even a quiet Christ-like quality to his vision of the world. In one of the film’s most touching scenes, Lois and Clark reflect on their “punk rock” upbringings:

Lois: “You think everything and everyone is beautiful.”

Superman: “Maybe that’s the real punk rock.”

It’s a simple exchange, but it captures everything about this Superman. Like Christ, he sees not the brokenness of humanity, but its beauty and potential. He chooses to love us anyway. He chooses kindness — an underrated value that could very well heal our culture, breaking through our biggest political divides to help us realize we are all human beings made in God’s image.

And that kindness changes people. Superman’s example inspires Metamorpho (Anthony Carrigan) and fellow Justice Gang members Guy Gardner (Nathan Fillion) and Hawkgirl (Isabela Merced) to stand up for the innocent people of Jarhanpur. Meanwhile, Mr. Terrific (Edi Gathegi) joins Superman in stopping Luthor’s plot to destroy Metropolis.

Despite everything — public outrage, alien expectations, media spin — Superman doesn’t abandon his ideals. He doesn’t lean into resentment or vengeance. He chooses instead the simple truths taught to him by his Earth parents, Jonathan and Martha Kent (Pruitt Taylor Vince and Neva Howell). In the words of the former: “Your choices. Your actions. That’s what makes you who you are.”

James Gunn’s “Superman” resonates because it dares to believe the best in people. No matter your politics, race, or religion, most of us are doing our best — even when we fall short. And if that’s considered “weak” or “woke,” we should ask what we’ve really come to expect from our heroes.

If kindness is the new punk rock, then maybe punk rock is what will save the world. And who better to lead that charge than Superman?

Did anyone want to revisit America circa May 2020? BLM. COVID-19. Mask mandates. Peak cancel culture. Social distancing.

No, thank you.

A throwaway scene finds a white teen describing his privilege to his gobsmacked parents. Their reaction is guaranteed to draw howls.

Somehow director Ari Aster makes it an invitation worth considering.

The director behind “Hereditary,” “Midsommar,” and “Beau Is Afraid” jumps into that awful, no-good chapter in U.S. history with “Eddington.” Those expecting another progressive screed from La La Land will be happily disappointed.

Nor is Aster gunning for a MAGA cocktail party invite. His tale pulls nary a punch, belittling both hard-right conspiracists and BLM types.

What’s maddening is the lack of discipline in the film’s third act. If you thought 2020’s Summer of Love protests proved chaotic, perhaps “Eddington’s” finale feels appropriate.

Otherwise, a potentially great film loses its way.

Joaquin Phoenix stars as Sheriff Joe Cross, an earnest lawman flustered by his state’s new mask mandates. It’s May 2020, and the country has already fallen for pandemic hysteria.

He tries to bring sanity to his New Mexico hamlet with few results. The locals have already adopted a mask-at-all-cost approach, including Eddington’s Mayor Ted Garcia (Pedro Pascal).

Mostly.

That drives Joe to impulsively declare his candidacy for mayor, much to the chagrin of his troubled wife, Louise (Emma Stone). She spends her days ducking his carnal advances and devouring conspiracy theories along with her hard-charging Ma (Deirdre O’Connell).

Meanwhile, the death of George Floyd sparks sympathetic protests across Eddington, straining the town’s wafer-thin resources. It’s neighbor against neighbor, and some of the young protesters barely know what they’re shouting about.

White privilege. Colonization. Racist cops. It’s a Mad Libs dash through progressive slogans, and it’s even sillier than what we remembered. The protests are a blindingly white affair, with BLM sympathizers torn between acknowledging their privilege and barking land acknowledgements.

One teen wants to get lucky, so he Googles “Angela Davis” just to break the ice with a pretty protester.

We can laugh about it now, but it wasn’t funny at the time. And sadly, remnants of that thinking refuse to slink away.

Aster isn’t sugarcoating far-left absurdism, although his hard-right conspiracies feel too cartoonish. The writer/director’s sense of editorial balance is shocking and smart. It’s a culture war movie that doesn’t look or sound like one.

The director leans into TikTok videos, YouTube confessionals, and cancel culture attacks — 2020 distractions that kept our attention during lockdowns.

The only thing missing? Netflix’s “Tiger King” series.

Sheriff Joe wants to have it both ways. He’s disgusted by residents trying to capture him in an unflattering light on their smartphones. He still turns to his phone to record campaign videos.

His political instincts, or lack thereof, are the film’s funniest running gags.

Aster’s setup is bracing and uncomfortable. Is it too soon to dissect this societal breakdown? The answer quickly becomes “no,” especially given how much we’ve learned about COVID-19, vaccines, and BLM-style activism since then.

“Eddington” isn’t a traditional comedy, but its satirical swipes leave a mark. A throwaway scene finds a white teen describing his privilege to his gobsmacked parents. Their reaction is guaranteed to draw howls.

Man, it feels good to laugh at that.

Eddington teens want to do something, anything, other than stay locked in their homes. So they join BLM and recite hackneyed slogans without actually understanding what they mean.

They look miserable.

The overstuffed story includes Austin Butler as an oily conspiracy theorist (is there any other kind?), a plot thread that adds a few chuckles to the story. Butler is a charismatic presence, but he’s not fully unleashed.

Aster never knows how to leave well enough alone — his 2019 misfire “Midsommar” felt longer than the Summer Olympics. That means “Eddington” overstays its welcome by at least 20 minutes (the film is just shy of two-and-a-half hours long).

The film takes a violent turn mid-movie but lacks the urgency of the best screen thrillers. Instead, we watch a key character scramble for his life while we wonder what, exactly, is happening on screen.

Little of it makes sense, and the film’s coal black humor takes a knee.

Phoenix gets the meatiest role as a troubled sheriff. Poor Joe is earnest but overwhelmed, trying to process our 24/7 digital age without much luck. Pascal’s mayor should have our sympathy, from his pro-masking stances to having “he/him” on his Zoom profile.

That’s how Hollywood movies work in 2025 ... right?

Instead, the actor makes sure to show his character’s smarmy side, and Aster refuses to deify a Hispanic leader.

“Eddington” is neither a lecture nor a cautionary tale. Aster serves up no solutions, only the potential for more misery. We already lived through the worst of what’s seen on screen, and laughing at it now offers a delicious, overdue sense of relief following those over-reactions.

We wouldn’t do that again. Would we?

It’s why the final, chaotic moments prove so dispiriting. “Eddington” eventually loses its way, and a bitter coda puts an exclamation point on that fact.

It’s high past time Hollywood grappled with the worst year in recent memory. Aster’s willingness to call out all sides makes "Eddington" a bracing, almost necessary watch.

The new “Karate Kid” movie has a surprising twist: older men teaching younger men to work hard, honor tradition, and develop a virtuous character. “Karate Kid: Legends” is exactly what you think it’s going to be — and thank God for that.

If, like me, you grew up trying to perfect the crane kick in the living room after watching the original “Karate Kid,” then this movie will hit all the right beats. It follows the classic formula: an underdog with raw talent, a wise mentor with quiet gravitas, a villain who cheats, and the enduring truth that virtue matters more than victory.

You might ask, “So ... it’s not a great movie?” No. It is just what you expect, and that’s what makes it great. It doesn’t pretend to be something else. It’s not trying to be edgy, subversive, or “reimagine the genre.” It isn’t the millionth movie in the “Sixth-Sense-twist-at-the-end” series of hackneyed films we’re all bored with. It’s just a good old-fashioned “Karate Kid” movie. And in an age when every studio seems bent on turning childhood memories into political lectures, this is a welcome roundhouse to the face.

The tradition here is simple and good: older men teaching younger men how to face suffering with courage and to live lives of virtue.

No woke sermon, no rainbow flag cameo character delivering predictable lines about systemic injustice, no Marxist backstory about how dojo hierarchies are tools of capitalist oppression — this isn’t a Disney film, and you can tell.

Instead, it asks a dangerous question, one so controversial it might get you fired from an English department faculty meeting: Do hard work, discipline, tradition, and honor still matter?

In the woke world, of course, the answer is no. Disney movies now teach that tradition is oppressive, virtue is repressive, and hard work is a tool of colonialist mind control. Your feelings are your truth — and your truth is sacred. If you feel like turning your back on your family to pursue LGBTQ+ sex, then you’re the greatest hero in human history. But “Karate Kid: Legends” doesn’t go there. It doesn’t need to.

It’s not a message movie. But it has a message. And it’s one even a child can understand: Be honorable. Do the right thing. Grievance and self-pity don’t lead to victory. And if they do, it’s a hollow one.

The film also manages to affirm tradition without being heavy-handed about mystical Eastern spiritualism or ancestral ghost sequences. Disney spews New Age spirituality in cartoons for kids at every opportunity.

The “tradition” here is simple and good: older men teaching younger men how to face suffering with courage and to live lives of virtue. That includes working through loss — deep loss, the kind that could break a person. But instead of turning to rage or self-indulgence, our young hero learns to endure, to persevere, to get back up — and maybe, just maybe, deliver that final clean kick.

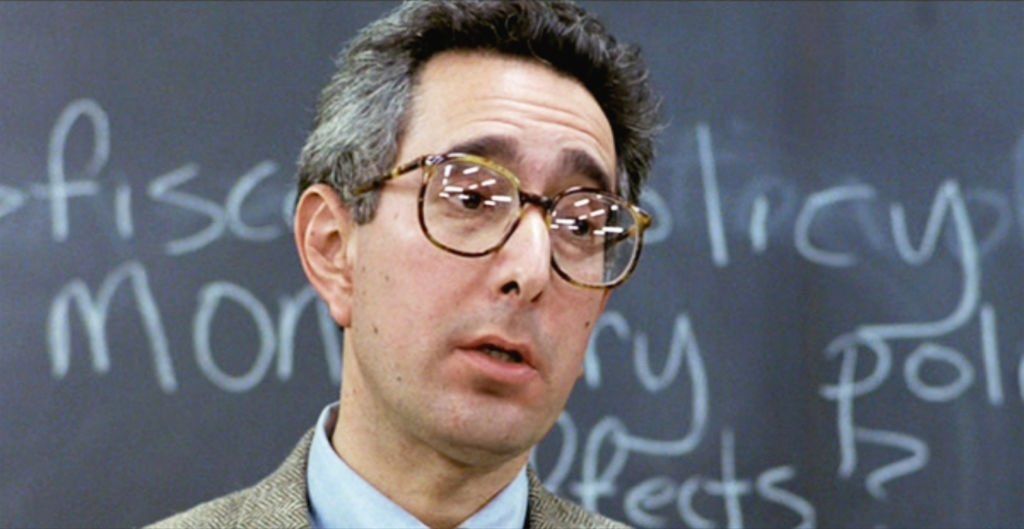

RELATED: Ferris Bueller's surprisingly traditional ‘Day Off’

Of course, there’s a villain who cheats. You’ve got to have that. And yes, he’s detestable. That’s kind of the point. As the smug leftist professor at your local state university might say, “So it’s about childish morality?” Yes, professor — it’s about what even a child can know: Doing the right thing and building character matters. Wallowing in the self-pity of grievance culture will never get you there.

Somehow, this simple truth has become controversial. In a world where adults cry on TikTok about microaggressions and activist professors turn every syllabus into a therapy session about their own victimhood, it’s refreshing to see a film that reminds us that life is hard. But that doesn’t mean we give up. It means we get better. Stronger. Kinder. More honorable.

And that’s what “Legends” delivers — without apology, without postmodern irony, and without the cultural sludge we’ve come to expect from Hollywood.

It’s clean. It’s earnest. It’s nostalgic without being desperate. And it shows us a vision of manhood and mentorship we desperately need: older men guiding the next generation, not with snark or shame, but with honor, wisdom, and love.

So if you want a movie that will entertain your kids without corrupting them — and hopefully inspire them to build a virtuous character — go see “Karate Kid: Legends.” It may not win an Oscar (which already tells you it’s good), but it might just help restore your faith in simple, straightforward storytelling. And that’s worth more than a golden statue.

Last spring's "Civil War" treated audiences to the spectacle of America finally quelling a MAGA-coded revolt that had split it in two.

The movie's Trump-like villain played on fears that the defeated president's comeback bid — at the time building momentum — might actually work. His cowardly, ignominious death at the end offered reassurance that we would soon witness Donald J. Trump's permanent exit from the political scene.

'She’s the Mamala of all Mamalas,' gushes Daily Beast film critic Nick Schager.

Who knew that a scant few months later, reality would hew so literally to fantasy? Unlike his fictional counterpart, of course, Trump survived — and he did so with a stirring display of courage that arguably clinched his victory that November.

By now, the country has more or less accepted Trump 2.0. Yes, there is still a "resistance," but it lacks energy and focus; all but the most recalcitrant Democrats have started to turn their gaze inward.

Under the circumstances, a movie featuring a Kamala Harris-like president kicking butt and saving the world might be considered in poor taste. In fact, Harris' campaign was such a disaster that one would expect Amazon Prime to shelve the movie entirely, just as any cinematic depictions of skyscrapers toppling were pulled following 9/11.

Nevertheless, "G20" persists in trying to entertain a weary nation.

"G20" began production in January 2024, six months before Harris became the official Democratic candidate. Still, one can't help but sense a certain confident political prognostication in the setup. If so, the filmmakers were widely off the mark, and now the film must be enjoyed as a bittersweet, Quentin Tarantino-esque exercise in alternate history: What if Orange Hitler had been taken out?

The critics seem to have taken the bait. “She’s the Mamala of all Mamalas,” gushes Daily Beast film critic Nick Schager.

“[Viola Davis is] Kamala Harris via John McClane, John Wick, Rambo, and Harrison Ford’s 'Air Force One' leader. … Part 'Die Hard,' part wish-fulfillment saga for a post-2024 present that didn’t come to pass, it’s a fantasy of feminist and U.S. might that’s chockablock with implausibilities.”

"G20" follows President Danielle Sutton attempting to solve world hunger in third-world countries through an ambitious digital currency project. Due to her perceived weakness in diplomatic skills and a rowdy partying daughter running around embarrassing her, Sutton is struggling to get her plans taken seriously.

Attempting to sell the plan at the annual G20 Summit, she finds the event attacked by terrorists looking to enrich themselves through a global cryptocurrency pump-and-dump scheme. Having escaped the attack, Sutton is now locked in the building as the last hope to save the global economy by using her latent skills as a former soldier to fight back and sneak through the massive compound.

In other words, what we have here is indeed another version of Bruce Willis' John McClane. Not a problem in itself; many perfectly decent movies have emerged from the basic premise: "Under Siege," "Speed," "The Rock," "Run Hide Fight," as well as the rah-rah pro-Obama actioner "White House Down" — to which this film feels eerily similar.

But like all movies in the genre, what it does with the setup is what sets "G20" apart, especially given that it wears its politics on its sleeve.

Star Viola Davis ("Woman King," "Suicide Squad") has downplayed any overt comparison to Harris in her interviews, stressing that we never find out which party her character belongs to. She's been content to note with some melancholy that, “I do not think it’s a suspension of disbelief to imagine someone who looks like me as the president,” while stating that she just wants the film “to reach people.”

And yet her president Sutton parallels Kamala Harris to such an extent — from her fashion and haircut to the criticisms she endures — that it's impossible not to make the comparison. And while it’s a modestly entertaining actioner, the end product feels distracting and flawed.

For an action flick, it spends too much of its precious screen time dialoguing about the global monetary system and the perceived weakness of the dollar. As RogerEbert.com's Daniel Roberts puts it, “the script is so issues-based that it strangles the film’s mood.”

Wonkiness aside, at its core "G20" is the story of a strong woman of color triumphing over misogyny and racism to earn her place as the most powerful leader in the world. She’s doubted by everybody from the U.K. prime minister to the press, but slowly earns their respect until even her rebellious daughter is calling her a “badass.”

By the end of the movie, President Sutton can do no wrong. While we're never told her approval rating, we can only imagine she's putting up first-term Obama numbers. And so "G20" offers an escapist fantasy for anyone traumatized by Trump's relentless efforts to make good on his promises.

Remember the old protest sign — "If Hillary won we'd be at brunch right now"? It still holds true. Imagine if the media-generated cult of Kamala had had actual popular support. Instead of immigration and tariffs, our table talk would mostly concern the failure of Republicans to take the first black woman president seriously.

Another round of mimosas! Come to think of it, "G20" may be the scariest horror movie you've seen in years.

I don’t throw around the word “masterpiece” lightly. In fact, I’ve developed something of a reputation for being hard to impress. I don’t think that’s unfair. My standards aren’t unusually high — contemporary standards are just too low.

So when I find something that deserves real praise, I won’t hold back. And the new animated film “The King of Kings” comes about as close to a masterpiece as anything I’ve seen in a long time.

Sola scriptura doesn’t mean solo scriptura. Artistic license is perfectly legitimate — so long as it serves, rather than subverts, the gospel message.

The latest release from Angel Studios is the most compelling telling of the gospel for children I’ve ever encountered — and I’ve seen plenty as a homeschool dad. Honestly, it’s one of the best animated films I’ve seen in years, period.

Framing the story with Charles Dickens as narrator was a brilliant decision. Dickens, arguably the greatest storyteller in the Western canon, guides the audience through the life of Christ by telling it to his young son for the first time. That structure — Dickens’ son imagining the gospel story and entering the narrative — creates a vivid, emotionally immersive experience.

It works. In fact, it’s what makes the whole film so powerful.

To witness the gospel again, this time through a child’s innocent eyes, restored my own “faith like a child.” I choked up more than once, as did my wife. The film’s depiction of the great exchange — Christ’s life for ours — comes through in a way that a child can grasp and can move adults to tears.

The animation is exceptional. Multiple visual styles blend seamlessly. The voice cast includes familiar names, many with more major awards than Ralphie’s old man. This isn’t just Christian entertainment — it’s top-tier craftsmanship. The filmmakers took excellence seriously. They treated the source material with the respect it deserves.

Audiences noticed. “The King of Kings” became the top new release in the country.

There’s a message here — one Hollywood and faith-based filmmakers alike would do well to hear.

To Hollywood: Enough with the agitprop. Stop desecrating beloved stories with political sermons. Honor the source material. The audience will show up.

To faith-based creators: Make something great first. Let its moral or religious value emerge from its quality — not the other way around.

A final word to my fellow believers: I know it’s easy to nitpick. I do it myself. But don’t become the kind of person who’d complain about being hanged with a new rope. The Gospel of John ends with this:

Now there are also many other things that Jesus did. Were every one of them to be written, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written.

The Bible never claims to include every word or deed of Christ. And telling a story for modern audiences sometimes requires creative choices. That’s not heresy. That’s storytelling. Sola scriptura doesn’t mean solo scriptura. Artistic license is perfectly legitimate — so long as it serves, rather than subverts, the gospel message. That goes for more than just “The King of Kings.”

Soapbox dismounted. Time for you to get off the couch and go see this movie.

Editor's note: "The King of Kings" and distributor Angel Studios are sponsors of BlazeTV. The independent views of the author do not necessarily represent the views of Blaze Media.

Mary the mother of Jesus was remarkable for one very important reason: God chose her (and Joseph) to raise the Son of God.

"Mary," the new Netflix movie, is not remarkable. For a (heavenly) host of reasons.

My hopes were dashed when Mary announces somewhat defiantly, looking straight into the camera: 'You may think you know my story. Trust me. You don’t.'

First, let’s get this straight. Mary was not born holier than anyone else. She was just a normal girl with a heart to please the Lord, as evidenced by her reaction to the angel Gabriel giving her the news that would change her life forever. From this reaction, we can deduce that her family was likely devout. They had arranged an engagement for her, as was culturally customary. And her fiancé, Joseph, proved himself worthy by his kind intentions toward her even when he thought she had betrayed him.

You can read this whole narrative in Luke 1:26-38 and Matthew 1:18-25. And I suggest you do, because that’s the real story. Netflix could have made a beautiful movie telling that story — it’s full of drama and mystery and fear and hurt and love — but director D.J. Caruso, along with executive producer (and televangelist) Joel Osteen, chose to tell an entirely different story. An unbiblical story.

And it’s not even a good unbiblical story.

Film scripts based on the Bible run the gamut from straight scripture (like 2003’s "The Gospel of John"), to fanciful depictions that spin off so wildly from the Bible that the message and meaning of the biblical text is completely twisted (looking at you, Darren Aronofsky, for messing with "Noah").

Somewhere in the middle there I’d put "The Chosen," Dallas Jenkins’ multiple-season series on the life of Jesus. It’s firmly rooted in scripture, but Jenkins attempts to flesh out the story (with often-but-not-always historical and cultural context) to help us imagine what it must have been like for regular people who encountered Jesus Christ. Much of the time these efforts are successful; sometimes not so much.

I was hoping that "Mary" would be like a good episode of "The Chosen," but alas my hopes were dashed almost from the film’s first moments, when Mary announces somewhat defiantly, looking straight into the camera: “You may think you know my story. Trust me. You don’t.”

If a film billing itself as an “epic biblical” tale tells us from square one that it’s going to tell us the “real” story, it is no longer biblical (and probably not epic either).

The entire premise of this film is the entirely imagined idea that Mary was no humble teenage girl but was special from before she was born.

This is evidenced by the angel Gabriel visiting both her parents to inform them that their childlessness was about to end with a special daughter who would belong to God.

As a child, flocks of butterflies follow her around, and people stare at her, sensing ... something. Her parents eventually fill her in on her status and tearfully deliver her to the temple to serve God as part of some weird underage girl temple helper group, which I am fairly certain was not a thing (there’s certainly no biblical mention of girls being dropped off to live in the temple, and it doesn’t seem like it would be culturally acceptable).

Plus, the outfits the girls wear look a bit like "The Handmaid’s Tale," so it’s a bit creepy.

Reality check: Mary did not know she was chosen until it was time for her to know. Her family didn’t know until she told them, and we can imagine that was a difficult situation.

Again, that might have made for some powerful film storytelling, if the filmmaker could have just stuck to the scripture instead of the script.

Speaking of the script, it’s packed with foreshadowing of elements from the life of Christ, including a disturbing scene where wicked King Herod presses a crown of thorns into the Jewish high priest’s head, blinding him (after which Herod stares at young Mary, also sensing ... something).

Eventually, they get around to the real story, when the angel Gabriel visits Mary, but they only stay with the Bible briefly before the film transitions to an action movie.

Crowds of Jews who hate the Romans are shown rioting and also trying to stone Mary for her out-of-wedlock pregnancy. Joseph is a full-on action hero who bravely fights his way out of this situation and a few others, eventually getting Mary to Bethlehem.

In the film, they went not to comply with the Roman census (the real reason they went there — see Luke 2:1-5) but because he “has family there.”

And this is where the movie’s plotline unravels completely. They make their way through the crowded streets of Bethlehem looking for a place to stay. Why? He just said he had family there. Mary then asks Joseph if all the people are there because of the census, but he tells her ominously, “No — this is something else.”

And then he finds out what that something else is, when a woman tells him: Everyone’s here because the Messiah is to be born here! And indeed later scenes after Jesus’ birth appear to show crowds of people coming to see Mary and the baby.

Mary was a devout “nobody” — exactly the kind of person God delights in using (and blessing). And almost nobody was reading the Old Testament scriptures looking for the Messiah.

Nobody was in Bethlehem expecting to be witness to the birth. Angels told a group of raggedy shepherds, and wise men (who did study the scriptures) followed the star.

There were no crowds. Most people, and certainly the religious authorities, were caught up in their conflict with the oppressive governing Romans, jockeying for position and obsessed with internal politics. Most were blind to the Messiah when he arrived on the scene 30 years later; they were certainly not interested in a humble teenage girl from Nazareth at this time.

"Mary" continues to spiral into nonsense.

Herod is enraged about a new king of the Jews being born and decrees all the baby boys in Bethlehem be killed (that really happened). He then asks them to bring back alive the one baby who is the actual problem baby (that didn’t happen, and why would it? In real life, he thought he was taking care of the problem by killing all the babies).

Also, please don’t fall into the giant plot pothole where huge crowds come to visit Mary and the baby but the murderous Roman soldiers could not find that same baby.

We haven’t even gotten to Joseph’s last action-hero scene where he fights off a platoon of fully armed Romans who are trying to set fire to them while Mary kicks out a window, action-hero style, and baby Jesus gets tossed down from a roof in a basket.

There's also some silly, self-empowerment dialogue, like when Elizabeth tells Mary to “trust the strength inside her,” which is simply not what a devout Jewish woman in first-century Israel would tell anyone to trust in. (It does sound suspiciously like the kind of thing televangelists like Osteen might say, though.)

But for all the foolishness of the action scenes, the real damage of this movie is perpetuating the myth that Mary was anything other than a normal human being.

She was chosen by God for a divinely appointed task, and he gifted her with everything she needed to fulfill that to his glory. But angels did not announce her coming, and butterflies didn’t follow her around. She was born in sin like every other human, and she was saved by his grace through her faith, like every other saint. Like all of us who call him Lord.