Not without my fur baby! Our bizarre new dog-worshipping religion

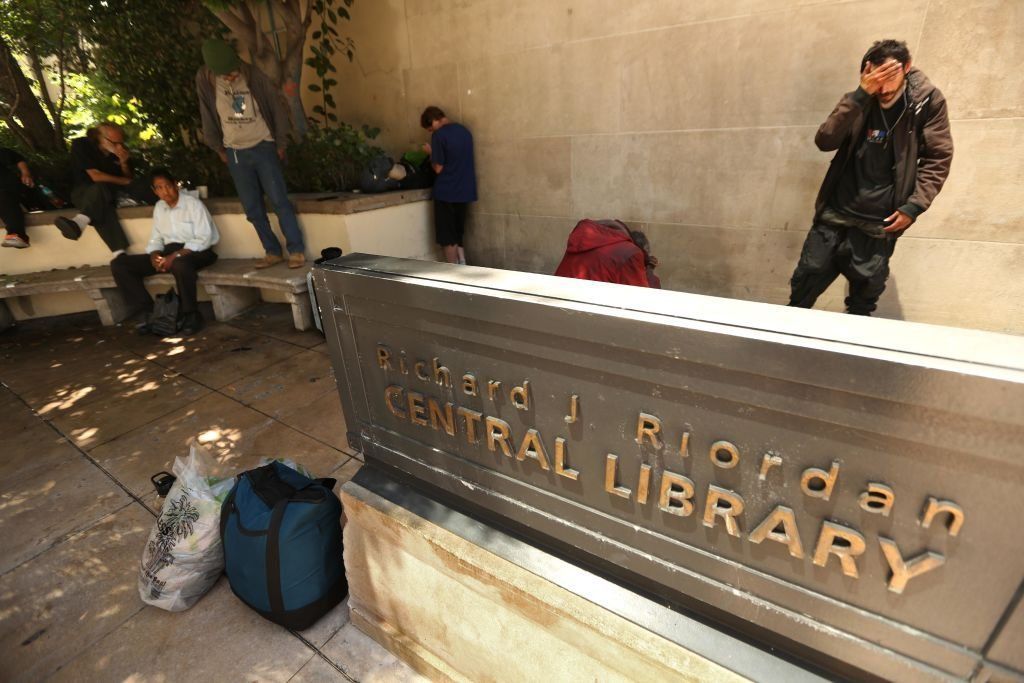

Dogs. They're everywhere.

Stores, cars, restaurants, coffee shops, bakeries, airports, and airplanes. Our world has been taken over by the K9s.

Banning dogs from certain places is now seen as 'exclusionary.' According pets human status — behavior once limited to the eccentric rich — is now everybody's prerogative.

Places previously reserved only for those who walk on two feet and upright are now open to all species. No beast is barred from the dairy aisle, no hound is left out in the cold.

I know it’s hard to believe, but it wasn’t like this until very recently.

Planet of the fur babies

Dog culture as we know it today was virtually unheard of when I was a kid. Traditionally, the only people who exemplified any kind of behavior resembling the “fur baby parent” of today were old, frail ladies who developed inordinately strong attachments to those little rat dogs with curly hair and an annoying yapping bark.

That archetype was goofy. That’s the other thing to remember. The old dog lady archetype was viewed as kind of silly. She wasn’t valorized, she was kind of made fun of, she was seen as odd.

Up until just a few years ago, dogs were never in stores. You didn’t see them inside the market, gas station, department store, or Home Depot. It simply didn’t exist.

RELATED: It’s way past time to ban pit bulls

Blind item

The only exception was a seeing eye dog accompanying a blind person, but even that was so rare that when it did happen, it was kind of cool.

I remember sort of standing back and watching, stupefied, feeling like I shouldn’t make any noises so as not to distract the dog. It was serious business. The dog was there for a purpose, and its purpose was to serve its master. That was, of course, the traditional purpose of dogs.

Dogs in restaurants were also, obviously, not a thing. Go back to the year 2000 and tell someone that in 25 years they will be sitting down to lunch in a cafe, eating a Caesar salad with a labradoodle to their left and a golden retriever to their right. Tell them that people will increasingly bring their dogs on airplanes, claiming they “need” them for “emotional support.”

This sweet, naive soul from Y2K might develop serious questions about the future and what went wrong.

Dog years

It’s important to remember what things were like. If we can’t remember what things were like, we are unable to accurately understand what it is that we are living in now. If we retcon the past, wiping our memories so we can live in a state or pure present where nothing ever gets better or worse, we are unable to grasp any broader trajectories of life, society, or culture.

But people don't like to be reminded of the fact that things were not always this way. They will resist admitting it. They will lash out if you remind them of it. They will find absurd edge-case exceptions to the truth in an attempt to convince themselves that things have always been this way.

It’s a fascinating phenomenon and a root cause of the inability to understand our culture and society. If you are convinced everything has always been this way, then any critique of the current reality feels like a critique of all reality, and instead of being anything insightful worthy of consideration, any critique can simply be dismissed as being overly negative.

Survival of the dimmest

Part of the reason people don’t want to be reminded of the fact that things were not always this way is because if they do realize things have changed, and are able to accurately judge the development of culture, they are more likely to correctly assess the negative developments and more likely to end up depressed about the current situation.

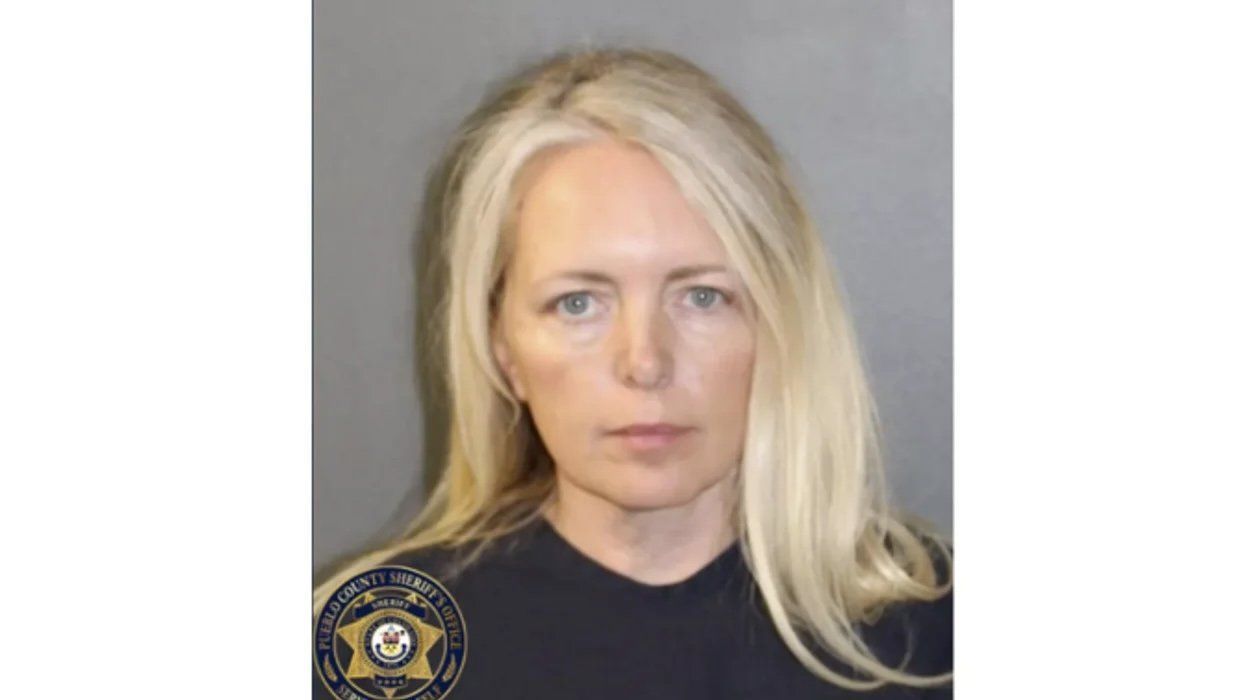

RELATED: Female arrested after her dementia-stricken mother, 76, was mauled to death in home with 54 dogs

Are they somehow anticipating this without realizing they are doing it? Is there some kind of purpose to not being able to remember the past? Is there some preternatural in-born resistance? Maybe most can’t handle the possibility that things are getting worse so there is something in us that basically tells us not to think about it too much. Maybe it is some strange ignorance, a bliss survival instinct.

In dog we trust?

Perhaps, it’s because dog culture is part of the new religion of our time, and the thing about religions is they are supposed to be eternally true, so if we can remember a time when none of this dog stuff was a thing, it casts some kind of doubt on the validity of this new secular religion.

Or even worse, if people can remember a time when they specifically weren’t into the dog stuff, or maybe even made fun of the dog stuff, they will do everything in their power to forget all about it and pretend they and everyone else were always the way they are right now.

People may also just be ashamed of the fact that our society has morphed into a society of frail, old, kooky dog ladies. If they have any sense of shame, they might just be embarrassed about this fact, and they might just try to forget how bad it is. Deflect, ignore, deny.

Whatever the reason may be, many people do not like to be reminded of the fact that things were not always this way.

An unhealthy trajectory

Is dog culture the worst thing in the world? No. But it isn’t a sign of a healthy trajectory. It’s a sign that something is off.

Banning dogs from certain places is now seen as “exclusionary." According pets human status — behavior once limited to the eccentric rich — is now everybody's prerogative.

That’s the new religion.

Our society no longer believes in the old hierarchy of man and animals. The beasts are now elevated to the place of man. That’s actually what’s happening beneath the surface, and it’s disordered. Somewhere, deep inside, people feel that, and they don’t want to be reminded of it because they know it’s wrong. At the very bottom, that’s why people don’t like to remember it wasn't always like this.