![]()

On April 2, President Trump announced a sweeping policy of reciprocal tariffs aimed at severing America’s economic dependence on China. His goal: to reshore American industry and restore national self-sufficiency.

How can the United States defend its independence while relying on Chinese ships, machinery, and computers? It can’t.

Tariffs aren’t just about economics. They are a matter of national survival.

But time is short. Trump has just four years to prove that tariffs can bring back American manufacturing. The challenge is steep — but not unprecedented. Nations like South Korea and Japan have done it. So has the United States in earlier eras.

We can do it again. Here’s how.

Escaping the altar of globalism

Tariffs were never just about economics. They’re about self-suffiency.

A self-sufficient America doesn’t depend on foreign powers for its prosperity — or its defense. Political independence means nothing without economic independence. America’s founders learned that lesson the hard way: No industry, no nation.

The entire supply chain lives offshore. America doesn’t just import chips — it imports the ability to make them. That’s a massive strategic vulnerability.

During the Revolutionary War, British soldiers weren’t the only threat. British factories were just as dangerous. The colonies relied on British imports for everything from textiles to muskets. Without manufacturing, they had no means to wage war.

Victory only became possible when France began supplying the revolution, sending over 80,000 firearms. That lifeline turned the tide.

After the Revolution, George Washington wrote:

A free people ought not only to be armed, but ... their safety and interest require that they should promote such manufactories as tend to render them independent of others for essential, particularly military, supplies.

Washington’s first major legislative achievement was the Tariff Act of 1789. Two years later, Alexander Hamilton released his “Report on Manufactures,” a foundational blueprint for American industrial strategy. Hamilton didn’t view tariffs as mere taxes — he saw them as the engine for national development.

For nearly two centuries, America followed Hamilton’s lead. Under high tariffs, the nation prospered and industrialized. In fact, the U.S. maintained the highest average tariff rates in the 19th century. By 1870, America produced one-quarter of the world’s manufactured goods. By 1945, it produced half. The United States wasn’t just an economic powerhouse — it was the world’s factory.

That changed in the 1970s. Washington elites embraced globalism. The result?

![]()

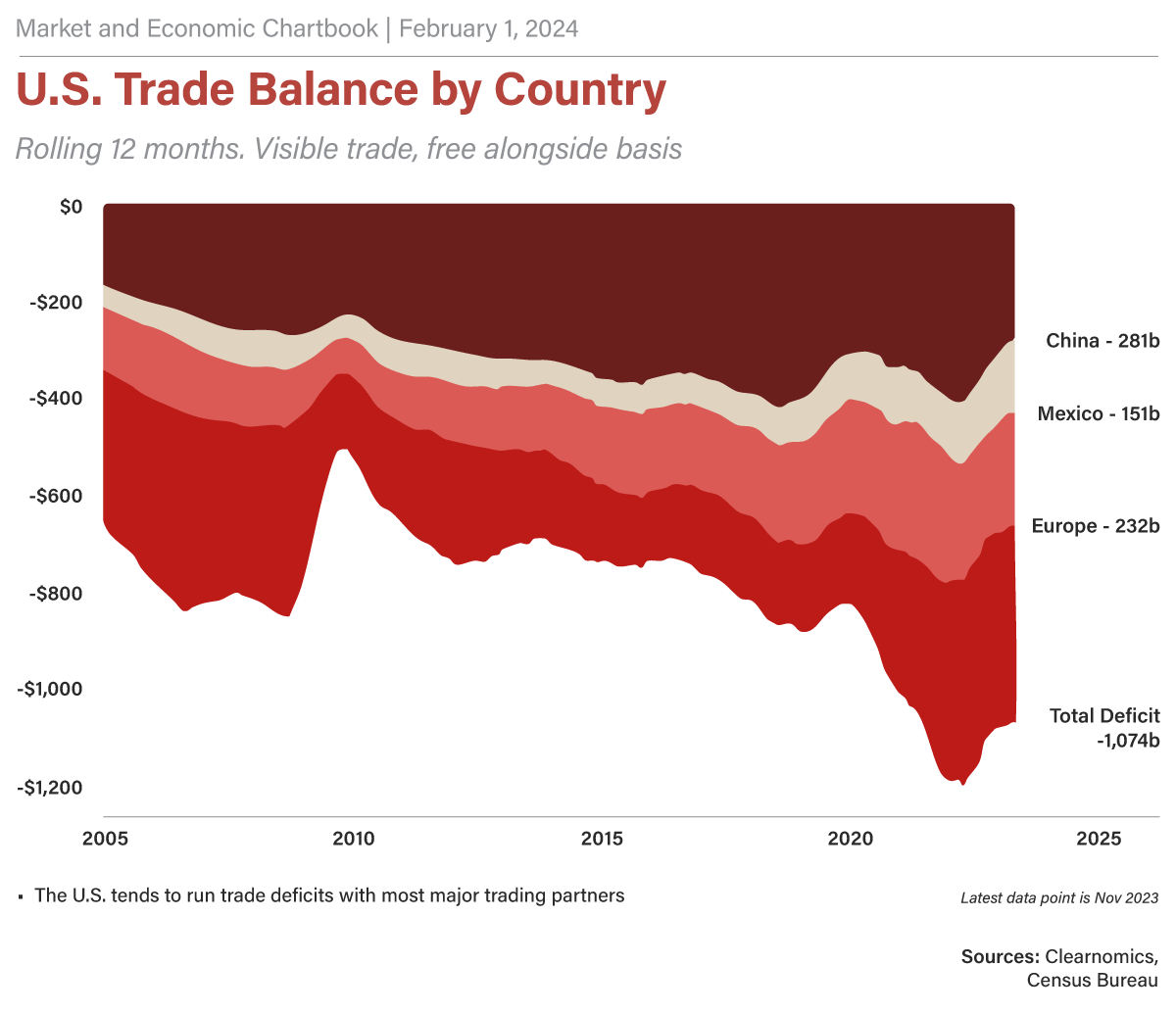

America has run trade deficits every year since 1974. The cumulative total now exceeds $25 trillion in today’s dollars.

Meanwhile, American companies have poured $6.7 trillion into building factories, labs, and infrastructure overseas. And as if outsourcing weren’t bad enough, foreign governments and corporations have stolen nearly $10 trillion worth of American intellectual property and technology.

The consequences have been devastating.

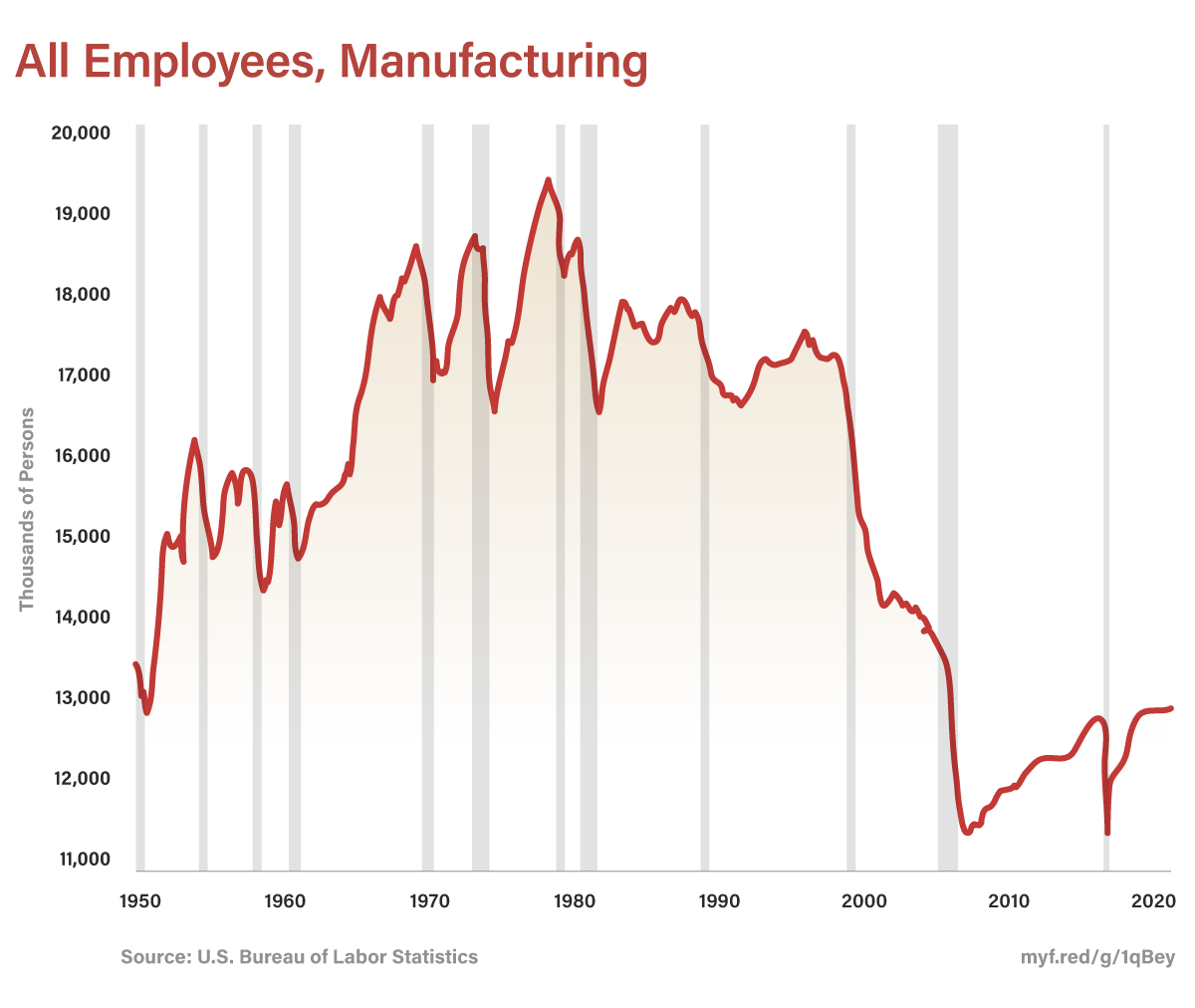

Since the 1980s, more than 60,000 factories have moved overseas — to China, Mexico, and Europe. The result? The United States has lost over 5 million well-paying manufacturing jobs.

![]()

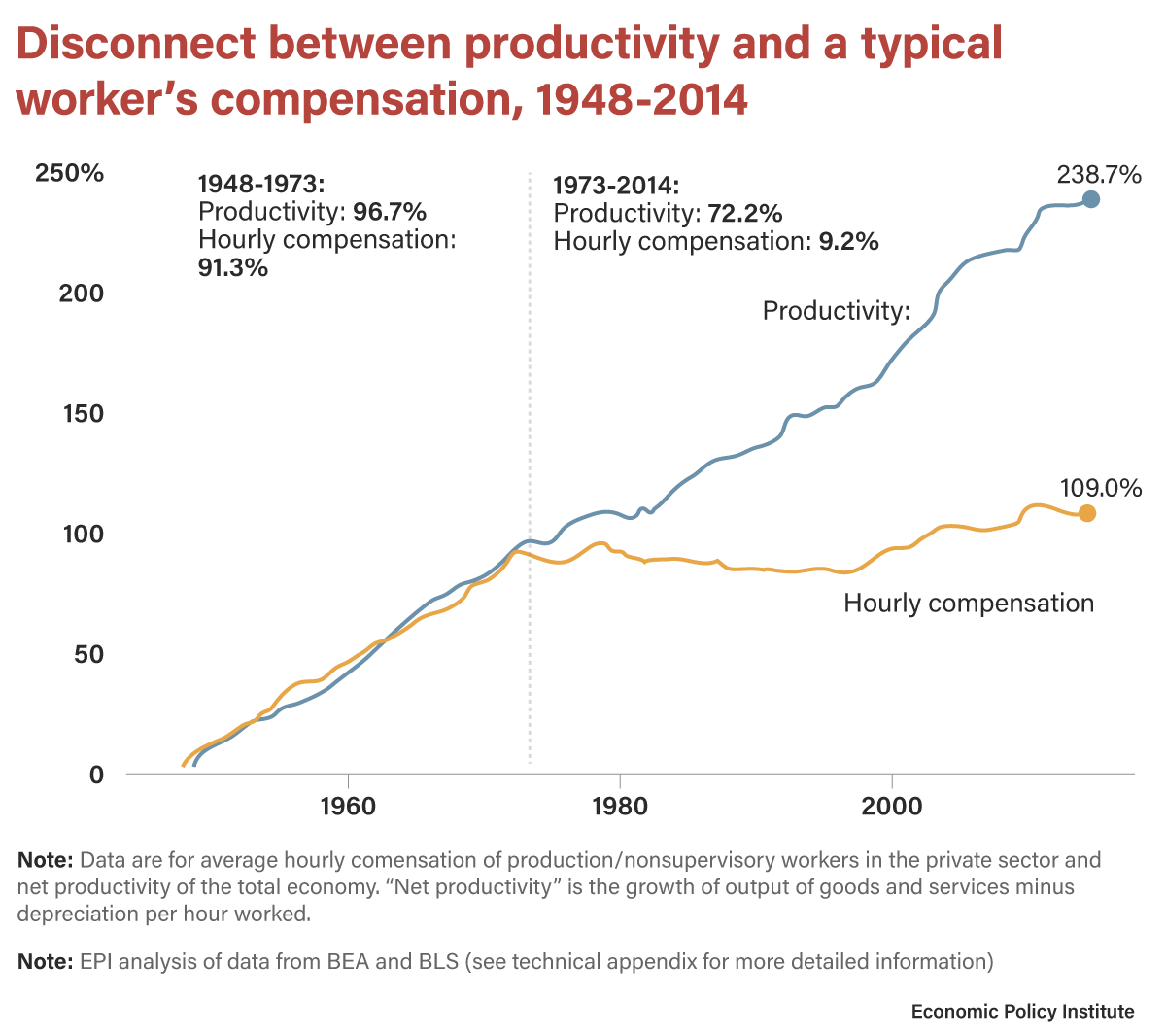

This industrial exodus didn’t just hollow out factories — it gutted middle-class bargaining power. Once employers gained the ability to offshore production, they no longer had to reward rising productivity with higher wages. That historic link — more output, more pay — was severed.

Today, American workers face a brutal equation: Take the deal on the table, or the job goes to China. The “race to the bottom” isn’t a slogan. It’s an economic policy — and it’s killing the American middle class.

![]()

Offshoring has crippled American industry, turning the United States into a nation dependent on foreign suppliers.

Technology offers the clearest example. In 2024, the U.S. imported $763 billion in advanced technology products. That includes a massive trade deficit in semiconductors, which power the brains of everything from fighter jets to toasters. If imports stopped, America would grind to a halt.

Worse, America doesn’t even make the machines needed to produce chips. Photolithography systems — critical to chip fabrication — come from the Netherlands. They’re shipped to Taiwan, where the chips are made and then sold back to the U.S.

The entire supply chain lives offshore. America doesn’t just import chips — it imports the ability to make them. That’s not just dependency. That’s a massive strategic vulnerability.

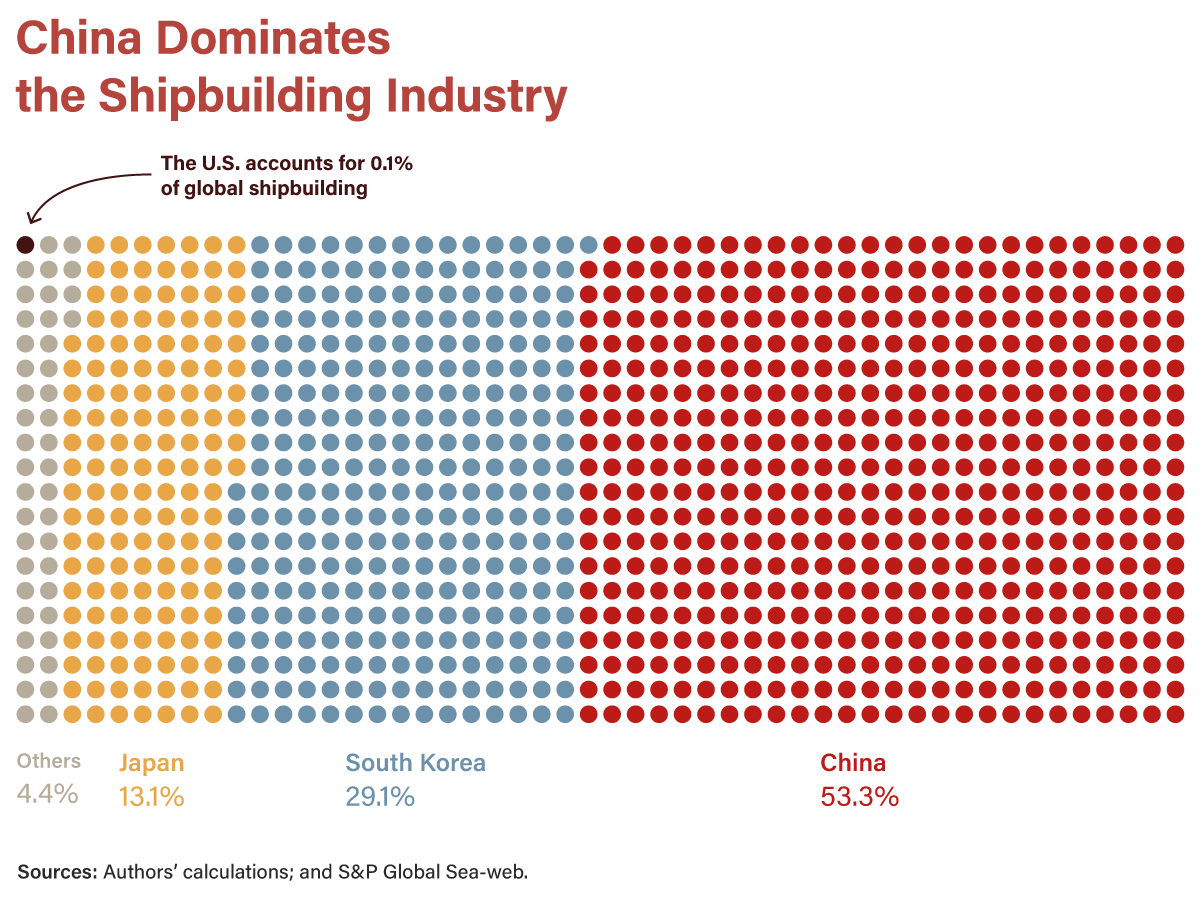

And the problem extends far beyond tech. The U.S. imports its steel, ball bearings, cars, and oceangoing ships. China now builds far more commercial vessels than the United States — by orders of magnitude.

How can America call itself a global power when it can no longer command the seas?

![]()

What happens if China stops shipping silicon chips to the U.S.? Or if it cuts off something as basic as shoes or light bulbs? No foreign power should hold that kind of leverage over the American people. And while China does, America isn’t truly free. No freer than a newborn clinging to a bottle. Dependence breeds servitude.

Make America self-sufficient again

Trump has precious little time to prove that reindustrializing America isn’t just a slogan — it’s possible. But he won’t get there with half-measures. “Reciprocal” tariffs? That’s a distraction. Pausing tariffs for 90 days to sweet-talk foreign leaders? That delays progress. Spooking the stock market with mixed signals? That sabotages momentum.

To succeed, Trump must start with one urgent move: establish high, stable tariffs — now, not later.

Tariffs must be high enough to make reshoring profitable. If it’s still cheaper to build factories in China or Vietnam and just pay a tariff, then the tariff becomes little more than a tax — raising revenue but doing nothing to bring industry home.

What’s the right rate? Time will tell, but Trump doesn’t have time. He should impose immediate overkill tariffs of 100% on day one to force the issue. Better to overshoot than fall short.

That figure may sound extreme, but consider this: Under the American System, the U.S. maintained average tariffs above 30% — without forklifts, without container ships, and without globalized supply chains. In modern terms, we’d need to go higher just to match that level of protection.

South Korea industrialized with average tariffs near 40%. And the Koreans had key advantages — cheap labor and a weak currency. America has neither. Tariffs must bridge the gap.

Just as important: Tariffs must remain stable. No company will invest trillions to reindustrialize the U.S. if rates shift every two weeks. They’ll ride out the storm, often with help from foreign governments eager to keep their access to American consumers.

President Trump must pick a strong, flat tariff — and stick to it.

This is our last chance

Tariffs must also serve their purpose: reindustrialization. If they don’t advance that goal, they’re useless.

Start with raw materials. Industry needs them cheap. That means zero tariffs on inputs like rare earth minerals, iron, and oil. Energy independence doesn’t come from taxing fuel — it comes from unleashing it.

Next, skip tariffs on goods America can’t produce. We don’t grow coffee or bananas. So taxing them does nothing for American workers or factories. It’s a scam — a cash grab disguised as policy.

Tariff revenue should fund America’s comeback. Imports won’t vanish overnight, which means revenue will flow. Use it wisely.

Cut taxes for domestic manufacturers. Offer low-interest loans for large-scale industrial projects. American industry runs on capital — Washington should help supply it.

A more innovative use of tariff revenue? Help cover the down payments for large-scale industrial projects. American businesses often struggle to raise capital for major builds. This plan fixes that.

Secure the loans against the land, then recoup them with interest when the land sells. It’s a smart way to jump-start American reindustrialization and build capital fast.

But let’s be clear: Tariffs alone won’t save us.

Trump must work with Congress to slash taxes and regulations. America needs a business environment that rewards risk and investment, not one that punishes it.

That means rebuilding crumbling infrastructure — railways, ports, power grids, and fiber networks. It means unlocking cheap energy from coal, hydro, and next-gen nuclear.

This is the final chance to reindustrialize. Another decade of globalism will leave American industry too hollowed out to recover. Great Britain was once the workshop of the world. Now it’s a cautionary tale.

Trump must hold the line. Impose high, stable tariffs. Reshore the factories. And bring the American dream roaring back to life.

Biden's tariffs play on the good intentions of voters, but all they do is raise costs for consumers and businesses and undermine innovation.

Biden's tariffs play on the good intentions of voters, but all they do is raise costs for consumers and businesses and undermine innovation. It’s time U.S. lawmakers force venture capital firms to stop fueling the growth of China's authoritarianism and military abilities.

It’s time U.S. lawmakers force venture capital firms to stop fueling the growth of China's authoritarianism and military abilities.