God Requires You To Agree With Democrats, Democrats Announce

People who live by the assumption that all faith is a meaningless and expedient surface posture can't speak to people who have actual faith.

People who live by the assumption that all faith is a meaningless and expedient surface posture can't speak to people who have actual faith.The mullahs of Iran have resumed the familiar work of slaughtering their own people. (Again!) The United States can respond without firing a shot — and without waiting months for a traditional embargo to bite.

It can impose an electronic embargo.

An electro-embargo could do something sanctions often cannot: break the regime’s control quickly enough to matter while the killing is still underway.

Washington could pursue this approach unilaterally, or it could press the United Nations to authorize it under Article 41 of the U.N. Charter, which empowers the Security Council to order measures “not involving the use of armed force,” including the partial or complete interruption of “postal, telegraphic, radio, and other means of communication.” The text already exists.

The question is whether anyone has the imagination — and the nerve — to use it.

In the context of Iran’s continuing humanitarian emergency, the United States, with a bit of diplomatic legerdemain from Ambassador to the U.N. Michael Waltz, could challenge the Security Council to act. China and Russia sit on the council. They will posture. They will threaten vetoes. But even a public debate would force them to explain why the world should tolerate a regime that murders civilian protesters in the streets.

If the Security Council approves an Article 41 action, the United States could then present its combatant commanders with something Iran has never faced at scale: an embargo not on goods but on electrons.

Physical embargoes remain a standard tool of statecraft. They also take time. Iran can evade, reroute, smuggle, barter, and stall. An electronic embargo moves at the speed of light.

Target Iran’s hardline regime — not the Iranian people — by degrading the communications infrastructure that allows the government to command and control its security forces and manage the extraction and export of oil, its primary source of hard currency.

Strike the regime’s hardened telephone and cellular systems, satellite communications, and broadcast television.

Cripple the internal nervous system that keeps the state coordinated, disciplined, and armed.

The effect would be immediate. A regime that cannot communicate cannot coordinate raids, deploy forces efficiently, jam dissident signals, or maintain operational tempo. It cannot manage a modern oil export apparatus without functioning networks. It cannot run a crackdown in real time if it loses the ability to issue orders and track compliance.

Just as important, an electronic embargo could reverse the regime’s favorite trick: cutting the Iranian people off from each other and from the outside world. Tehran has already tried to block the internet and throttle social media. A targeted electronic campaign could negate that control and unleash an information tsunami — one the mullahs cannot shape, censor, or contain.

That shift matters. When citizens can communicate, organize, document, and broadcast, repression becomes harder and riskier. The regime loses its monopoly on narrative. Fear starts to spread in the other direction.

RELATED: Memo to Hegseth: Our military’s problem isn’t only fitness. It’s bad education.

One can imagine a greatly expanded “Venezuelan formula”: degrade internal communications, then use broadcast means to confuse and complicate the regime’s grip on what is happening — while simultaneously encouraging the population to resist theocratic authority. The goal would not be spectacle. The goal would be collapse: the steady unraveling of the regime’s confidence, coherence, and control.

In this mode, a combatant commander could employ SOFTWAR principles to engage and degrade the mullahs through coordinated, non-kinetic lines of operation. Properly executed, such a campaign would affect nearly every aspect of Iranian society — and it would do so without turning Iranian cities into ruins.

The strategic payoff for the United States extends beyond moral clarity. It comes down to oil — and to China.

The recent decapitation of the Maduro junta in Venezuela proved a point many analysts ignore. The key factor is not the quantity of oil in a given country. It is control of the flow of oil. Energy states matter because they can fuel, fund, and sustain adversaries.

If the mullahs fall, China loses a major energy supplier at a moment when it can least afford disruption. Beijing’s ambitions depend on stable inputs. Xi Jinping’s dream of Chinese communist hegemony runs on energy. Remove an important provider, and you squeeze China’s strategic bandwidth — again.

That result alone justifies exploring an electronic embargo.

This is not a call for war. It is a call to use power creatively, within the bounds of international law when possible, and in defense of a population being beaten, shot, and silenced by its rulers.

The mullahs survive by controlling the physical streets and the electronic space above them. Take away the second, and the first becomes harder to hold.

An electro-embargo would not solve every problem. But it could do something sanctions often cannot: break the regime’s control quickly enough to matter while the killing is still underway.

Netflix just announced its next animated children’s film, “Steps,” a Cinderella inversion in which the evil stepsisters are the real heroes. Shocking, I know. The platform is also releasing “Queen of Coal,” a film about a “transgender woman” overcoming the patriarchy in his small Argentinian town.

Reports of the demise of wokeness were premature. Its adherents remain committed to pushing it across every domain of society. What’s notable is how boring it has all become. Deconstruction has been the default mode of modern culture, but it is running out of things to deconstruct. The transgression has lost its power as the taboo fades, and in that exhaustion, something new — perhaps something true — stirs.

The revolution brought destruction, but its exhaustion brings new possibilities.

Some call Friedrich Nietzsche the first postmodernist for announcing that “God is dead.” Whether he was a precursor or ground zero, the genealogy of the movement clearly flows from his work. You can argue about whether he unleashed several horrors into the world or merely acknowledged their arrival, but Nietzsche at least understood the seriousness of his claim. He understood that having the blood of God on your hands was not a clever academic parlor trick — it was monstrous.

With the creator of the universe declared dead, modern man felt free to dismantle the order that once bound him. The sacred bonds of hierarchy were shattered. Postmodernism launched its assault on the good, the beautiful, and the true. And breaking sacred bonds releases immense energy. The leftist revolution that consumed the West drank deeply from it.

The church, the community, the family, marriage, gender roles, gender itself — each time the left destroyed one of these natural structures, it seized the power trapped inside and wielded it against its enemies.

But deconstruction has a natural end point. Transgression requires something sacred to violate. As I have written before, you eventually reach the point where there is nothing left to transgress.

When every movie, show, novel, game, and song “subverts” the traditional Christian norm, the subversion becomes the norm. That’s why these Netflix offerings feel so lifeless: They all follow the same trajectory toward the same inversion.

Fifty years ago, critics complained that stories were predictable because the squeaky-clean hero always triumphed. Today they are predictable because the villain is always a misunderstood victim of bigotry who deserves to win. The inversion isn’t clever or subversive. It’s the boring status quo.

So what happens when postmodernism has inverted every hierarchy, mocked every sacred symbol, and squeezed the last drop of power out of attacking Christianity?

The philosopher Alexander Dugin offers a compelling answer. If modernity was the death of God, the end of postmodernism is the exhaustion of subversive secular culture. At that point, new possibilities appear. Instead of proclaiming that “God is dead,” people start asking, “The death of who?” The old order fades so completely that secular man forgets what he was rebelling against.

Meanwhile, the promise of becoming like gods and remaking the world in our own image begins to sour. We see the consequences of rejecting the good, the beautiful, and the true — and find them unbearable.

Postmodern man has lived his entire life in a world re-engineered from the top down by “experts.” When he cast God from His throne, man imagined he would shape the world through his own individual will. But the modern secular man discovers instead a moral wasteland. He finds that he is captive not to his own liberated self, but to darker forces once held at bay by the divine order he dismantled.

He no longer remembers what that order looked like — or why he rebelled against it. And in that moment, the opportunity to rediscover the spiritual returns.

RELATED: We’re not a republic in crisis. We’re an empire in denial.

The revolution brought destruction, but its exhaustion brings new possibilities. People have forgotten the object of their rebellion, and now they look at the miserable world secular man has made. They crave something more.

Order, duty, faith, meaning. These begin to look far more promising than the ugly, pointless chaos modern man created for himself. People once again thirst for a world where the good guy wins and God reigns.

The truth is that God never died. Christ died and rose again. Modern man tried to replace the divine with science and reason, but the Lord is the source of reason itself. He cannot be dethroned by His own creations.

As deconstruction loses its revolutionary energy and becomes stale, the desire to re-embrace sacred order returns. J.R.R. Tolkien captured this when he wrote: “Evil cannot create anything new. It can only spoil and destroy what good forces invented or created.” Eventually evil runs out of things to spoil. A barren, thirsty culture begins searching for the living water only divine truth can provide.

Modern culture is bankrupt, and everyone feels it. The attempts at transgression now read as hollow conformity to a corrupted system. We are not the masters of our own world or our own truth — and thank God for that.

We do not have to live in the nihilistic abyss we created. The natural order waits just beneath the surface, ready to re-emerge in a cultural revival.

The creative future will not come from a relativistic Hollywood clinging to the corpse of deconstruction. It will come from those willing to embrace the transcendent — from those who understand that the world is held together not by our will to power, but by the truth and beauty of our Creator.

Director David L. Cunningham brought some old-school Disney magic to his latest project.

The Hollywood veteran recalled how Walt Disney often appeared on camera to personally introduce the projects closest to his heart, putting his unmistakable stamp on them.

'By taking out the hardship and the risk, you diminish the courage that Mary and Joseph had, their faith, and so much of the sacrifice.'

So when Cunningham envisioned a fresh, authentic take on the Christmas story, he wondered if another icon could do the honors. And, as fate would have it, his producing partner knew Kevin Costner personally.

The busy film legend agreed to join the project, with one caveat.

“He insisted on bringing his story into it … and the pieces fell together,” Cunningham tells Align.

“Kevin Costner Presents: The First Christmas,” debuting Dec. 9 at 8 p.m. ET on ABC before hitting Hulu the following day, does more than put the Christ back in Christmas.

The special lets Costner share some personal anecdotes regarding the earliest days of his acting career, including how he participated in a Christmas story production with less than Hollywood-style results.

He improved over time, of course.

“The First Christmas” introduces us to Mary and Joseph, a young couple facing incredible hardships along with the most important pregnancy … ever.

“The intent was to try and find a unifying celebration of the story,” Cunningham says. “Let’s all get behind what matters the most. Jesus was brought into this world in this amazing way. … The goal wasn’t to put a spin on something but to revisit the ancient texts and try to honor it as much as possible.”

“The First Christmas” pushes past misconceptions about the holiday, blending polished dramatic beats with commentary bringing critical context each step of the way. That approach worked well with the material, the director says, comparing the expert commentary to “miniature podcasts” that pop in between dramatic elements.

“We didn’t want a theological, wag-your-finger thing,” he notes, but he also wanted to remove the “cozy interpretations” many have of the Nativity.

“By taking out the hardship and the risk, you diminish the courage that Mary and Joseph had, their faith, and so much of the sacrifice,” he says.

“There’s nothing wrong with having the cozy little Nativity, with the angels looking on, but let’s go back and revisit this and say, ‘Hey, what does the Scripture say and why?’”

The special features “talking head” interstitials from voices stateside and beyond, echoing Christianity’s global reach and impact.

“The West doesn’t have the corner on the [Christian] market,” Cunningham says, noting a spiritual rise in Brazil and other nations in recent years.

Cunningham is no stranger to faith-based productions, starting with one of his earliest projects: 2001’s “To End All Wars.” The film recalled the fact-based story of Japanese POW camp captives who embraced God to both endure and forgive their captors.

Those experiences have given him insight into Christian projects that connect with the masses and, more importantly, ring true.

“When a biblical movie works, it sticks to the text,” he says with a chuckle. “It also helps to have people who are leading the charge who believe in it.”

Cunningham studied faith-based films in film school, noting how the industry “lost the plot” over the years regarding Christian projects.

“We felt as Christians that somehow entertainment and Hollywood was of the devil. We didn’t want anything to do with it,” he says. “We just walked away from one of the most influential platforms there is.”

RELATED: 12 American-made Christmas gift ideas

That, of course, has changed dramatically over the past 20-odd years, from “The Passion of the Christ” to 2023’s “Sound of Freedom.” The clunky, low-budget stories of the recent past have been replaced by slick, soulful projects that reflect both faith and a dramatic upgrade in craftsmanship.

He name-checks “The Chosen” creator Dallas Jenkins and Jon and Andrew Erwin for being part of this cinematic revolution.

Cunningham also used his personal experiences to help inspire and shape “The First Christmas,” echoing what Costner brought to the project. He recalls his own days as a young father, with all the fear and uncertainty that came along with it.

“I’m walking out the door with this child. ... We had a car seat ready to go,” he says of his earliest hours as a parent. “Can you imagine a young couple in a cave when infant mortality was through the roof? Now you’re being born into this world that’s incredibly brutal and cruel. You’re a young couple, and by the way, that’s the Son of God.

“No pressure,” he says.

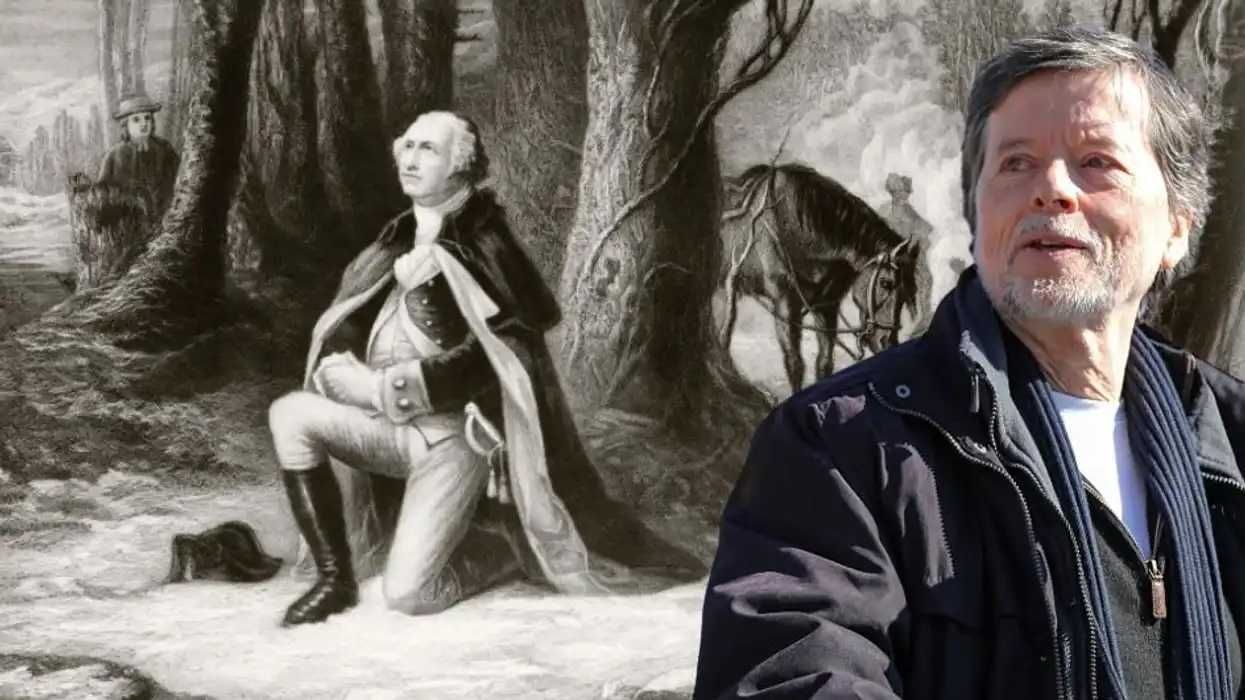

If America had an official "documentarian laureate," Ken Burns would be a shoo-in for the job.

Over the last four decades, the filmmaker has devoted his career to capturing the country's history and culture, in works ranging from "Baseball," "Jazz," and "The National Parks: America's Best Idea" to his groundbreaking 1990 masterpiece "The Civil War." And despite his avowed "yellow-dog Democrat" tendencies, he has done so with remarkable nuance.

Those rallying around the American cause are portrayed as a loose collection of criminals, anarchists, slavers, and exiled aristocrats united by high Enlightenment ideals.

Now, just in time for America’s 250th anniversary, Burns has returned with a new six-part PBS series exploring how it all got started.

"The American Revolution" arrives with suitable fanfare — and an almost absurdly star-studded cast of voice-over artists. Tom Hanks, Morgan Freeman, Samuel L. Jackson, Paul Giamatti, Josh Brolin, Meryl Streep, Ethan Hawke, Edward Norton, and Michael Keaton are among the luminaries who provide narration.

Even so, there has been a level of apprehension surrounding the show, particularly among conservatives. Could a commemoration of America's founding even work in our current moment — when even mild appeals to patriotism and national unity seem to stir up bitter partisan disputes?

Burns seems to have a found a way around this by making his retelling as clinical and unromantic as possible. He is clearly passionate about the American project, but he is unwilling to embrace the mythological or nationalistic sides of that passion.

“It’s our creation story,” historian Rick Atkinson says as he discusses the importance of the Revolution. But most of the experts Burns showcases prefer to focus on the negative, puncturing what one calls the “unreal and detached" romanticization of the founders.

Instead, we're invited to ponder the role that slavery and the theft of Native American land played in the fight for independence — not to mention a fair amount of unsavory violence perpetrated by the revolutionaries.

While the series does a good job of covering the conflicts between 1774 and 1783, it takes frequent detours to discuss the issues surrounding the revolution: the role of women contributing to the war, the perspectives of English Loyalists as they became refugees fleeing the conflict, the madness of the Sons of Liberty’s antics, and the perspectives of slaves trying to survive and find liberty too.

RELATED: Yes, Ken Burns, the founding fathers believed in God — and His 'divine Providence'

A pronounced classical liberalism pervades the storytelling, one reflecting the secular Enlightenment idealism that a “new and radical” vision for mankind could be found through self-determination and freedom, apart from the aristocratic and theocratic haze of Europe.

This vision acknowledges progressive criticism of the era’s slavery and classism, but tries to integrate those faults rather than use them as grounds to discard the entire experiment. It attempts to live within the tension of history and sift out what is still valuable, rather than abandon the project altogether.

Indeed, Burns is generally good about avoiding any sort of score-settling or modern politicking, shy of a few buzzwords. He constantly uses the word “resistance” and ends with a reflection on the potential ruination of the republic by “unprincipled demagogues,” proudly quoting Alexander Hamilton that “nobody is above the law.”

The show’s consensus is overwhelmingly that the values of the Revolution were greater than the severely flawed men who fought it. To Burns, it was not merely a war, but a radical ongoing experiment in human liberty that escaped the colonies like a virus and changed the world forever. He certainly doesn’t want to throw out the liberal project, and so he constantly circles back on defending the war’s idealism.

This accounts for the show’s title, focusing on its revolutionary implications. It wasn’t just a war, but a change in the way people thought. The show argues that “to believe in America … is to believe in possibility,” and that studying the Revolution is important to understanding “why we are where we are now.”

Unfortunately, the intervening 12 hours require the viewer to swallow a fair share of dubious and rather inflammatory claims, including that George Washington was primarily driven by his class interests as a landowner, that popular retellings often “paper over” the violent actions of the revolutionaries, and that the founders were, on balance, hypocrites.

Its overall perspective is that it is impossible to tell the nation’s origin story in a way that is “clean” and “neat,” with clear heroes and villains. Those rallying around the American cause are portrayed as a loose collection of criminals, anarchists, slavers, and exiled aristocrats united by high Enlightenment ideals.

"The Revolution" wants both this idealism and discomfort to sit equally in your mind, as you ponder how morally compromised men could change the world. As one of the historians asks, “How can you know something is wrong and still do it? That is the human question for all of us.”

Overall, Ken Burns’ latest proves a very bittersweet watch, hardly the sentimental reflection on Americanism that the country’s approaching 250th anniversary demands, but also too idealistic and classically liberal to comfortably fit anyone’s agenda. It wants to lionize the founding’s aspirational values of democracy, equality, and revolution, while assiduously avoiding praising the people involved.

It's a remarkably watchable and entertaining work of sober disillusionment.

The days of "The Wire," "The Sopranos," "Boardwalk Empire," "Breaking Bad," and "Better Call Saul" are gone. And they're never coming back.

Instead of quality TV, we get a stream of shallow muck that insults our intelligence and wastes our time. Seth Rogen peddling the same stale stoner humor for the thousandth time. Pedro Pascal starring in a dystopian video-game adaptation so obsessed with gay "representation" that it might as well list Grindr as a co-producer.

Sheridan shows a country held together by early mornings, long shifts, and people who take pride in work most citizens rarely notice.

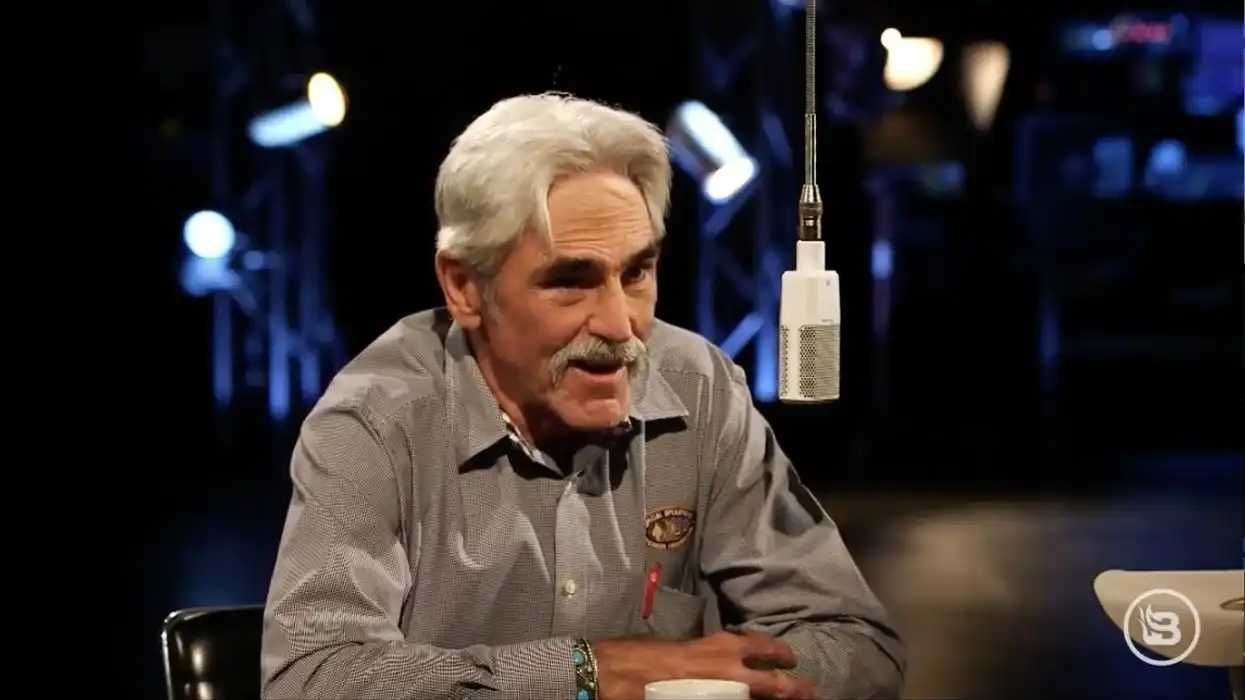

Then, just as you’re about to suffocate in the hothouse atmosphere of algorithm-driven fake-prestige TV, one show comes stomping in with a pair of steel-toed boots and kicks the door off its hinges. Fresh air floods the place — enough that something real might actually grow again. That show is "Landman."

Forget "shame"; it's time to drill, baby, drill. Taylor Sheridan's hit is back for season 2, with the TV auteur once again proving that he is one of the few people in Hollywood who actually understands the America he is depicting. Many viewers know him from "Yellowstone," the rare modern hit that refused to treat ranchers the way Hollywood treats anyone who still works with their hands. Where executive elites see deplorables, he sees Americans with stories worth telling.

Sheridan brings that same respect to "Landman." He writes ordinary Americans with dignity rather than derision. He shows them as they are: hardworking, flawed, loyal, funny, and strong enough to carry a story on their backs. "Landman" is no cheap cousin of "Yellowstone." It stands tall: lean, mean, focused, and built with the same skill that made Sheridan’s early work impossible to ignore.

The show moves effortlessly between blue-collar reality and white-collar brutality, revealing the canyon between those who pull the oil from the ground and those who profit from it. There’s a real honesty to that contrast. Sheridan knows this world, and it shows. You feel it in every shot of the Permian Basin. You hear it in the blunt, believable way his characters speak.

And then there’s Billy Bob Thornton. One of America’s finest actors, doing his best work since he stole "Fargo" as a soft-spoken psychopath who could change the temperature of a room with a single line. As Tommy Norris, a ruthless oilman, he brings back that same menace, just a little more restrained. He’s the perfect Sheridan creation: bruised, stubborn, quick to size people up, and capable of cruelty when pushed.

Season 1 worked best when it put Norris at the center and let everything else orbit around him. The very first scene of the very first episode sets the tone. Norris, blindfolded in a room with a cartel heavy, cracks a dry line about how they both traffic in addictive products. His just happens to make more money. It’s a joke with teeth. Sheridan doesn’t shy away from the darker corners of the oil world, the places where danger, deceit, and obscene wealth share the same bed.

Norris once ran his own outfit. Now he’s a fixer for M-Tex Oil, answering to Monty Miller, a billionaire played by Jon Hamm of "Mad Men" fame. Hamm leans into one of the last great “man’s man” roles on TV. He moves through marble corridors and executive suites with the relaxed confidence of a man who has never had to fight for a parking space or a paycheck.

Norris gets the other Texas. The asylum-adjacent McMansion he shares with co-workers. The long, unforgiving drives that eat up whole days. And the late-night waffle joints where truckers, rig hands, and the down-and-outs swallow bad coffee and brood over worse decisions.

Sheridan shows a country held together by early mornings, long shifts, and people who take pride in work most citizens rarely notice. He zooms in on communities where faith still shapes daily life, where people curse when they have to, where men bow their heads before a meal and chew tobacco like there’s no tomorrow.

For conservatives, and especially for Christians who are tired of being reduced to stereotypes, "Landman" feels recognizably real. Season 1 had its flaws, including a few moments that leaned too hard into climate panic, but it never lost sight of what matters: good storytelling built on real characters and real consequences.

RELATED: 'Yellowstone' actor Forrie J. Smith on why America needs to rediscover its cowboy culture

And yes, the progressive pearl-clutchers will claim "Landman" has a “woman problem,” the same complaint they threw at "Yellowstone." They insist that Sheridan sidelines women or turns them into cardboard cutouts.

The truth is far less dramatic. Both ranching and the oil fields are worlds dominated by men, and Sheridan writes them as they actually are, not as activists wish them to be. That’s not misogyny, but an accurate reflection of the reality millions of Americans live every day. Sure, some female characters could use more lines, but that hardly damages the show. It simply acknowledges that in these worlds, the danger, the decisions, and the dirty work fall mostly on men.

"Landman" also has something most modern shows forget: a genuine sense of place. Not the packaged Americana you see on postcards, but the West Texas that actually exists, where the heat melts your mind and vacation time is something you hear about, not something you get.

Season 2 promises to go deeper — underground for the oil and under the skin of the people who pull it out. More tension between the barons and the boys in the mud. More of Thornton’s world-weary wit. And more of what Sheridan does better than anyone around: crafting TV that wouldn’t look out of place beside the giants of the late 1990s and early 2000s.

If "Yellowstone" was Sheridan’s hymn to the American ranch, "Landman" is his sermon on the American worker. In an age of narrative nothingness, something on TV finally feels worth watching.