Forget streaming — I just want my Blockbuster Video back

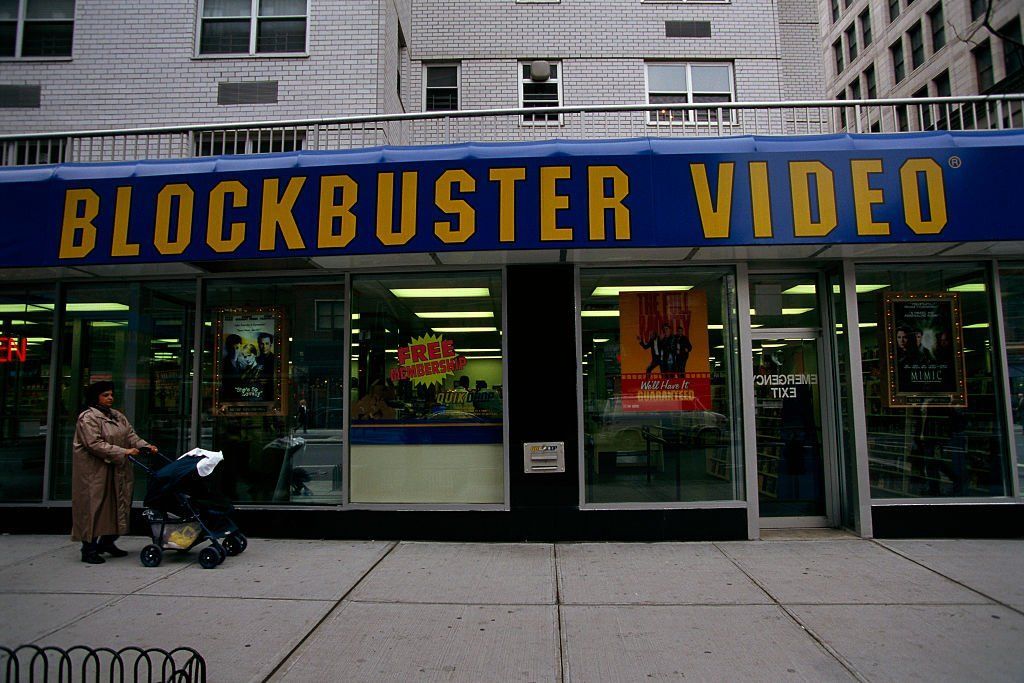

I remember going to Blockbuster with my mom and dad. It was down the street in a strip mall that was shaped like a capital L. It was on the very end and the corner.

It felt far away from our house, though I’m sure it wasn’t. Everything feels far away when you’re a kid. I had no idea how we got there either — which streets we took, how many turns were made, how many miles away it was, or even how long it took us to get there. Ten minutes? An hour? They kind of blend together when you’re a kid, and I had no real idea about any of it.

Blockbuster nostalgia isn’t really about the VHS or the strip mall, the warm smell of the tape or the quiet in the room. It’s about a longing for limitation, our secret wish for less.

But I remember riding in the back seat, looking out the window as my parents weaved the car through what seemed like a dizzying labyrinth of concrete, ranch houses, and tall trees on the way to Blockbuster.

Strip mall arcadia

Blockbuster had a distinct smell. Soft, warm, plasticky. The Louisville sun beat down through the big, long windows, coming in over the black parking lot and then falling down onto the rows of VHS tapes and low-pile carpeting.

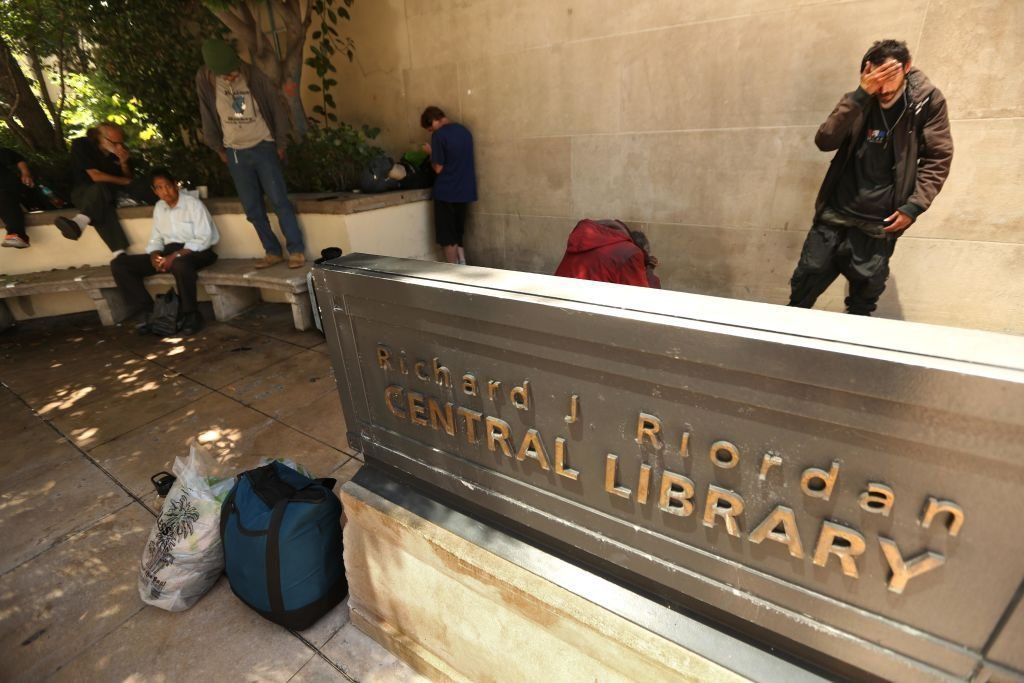

It’s funny to think, but the chain video store almost had the same feeling as the library. Rows of neat shelves adorned with a variety of titles. A hushed hum over the large carpeted room. Late afternoon in a sun-dappled Blockbuster, searching for the evening’s entertainment.

Now we don’t go to Blockbuster. They’ve been shut down a long time, and that flimsy blue and yellow Blockbuster card was thrown in the trash years ago. Now we don’t go anywhere.

We sit at home, fumbling around with the remote, clicking through seemingly endless options on Netflix. Everything “looks good” and is packaged up real tight, and there is more of it to watch than we have time. But nothing really is that good, or nothing really seems very good. Life’s not like it was at Blockbuster in 1998.

RELATED: 'All about the experience': Former Blockbuster and 7-Eleven CEO explains why we can't let go of the '90s'

Please rewind

What is my nostalgia — no, our nostalgia! — for Blockbuster? Why go back to the clunky, “be kind, rewind” technology of VHS? Why would it be nicer to be forced to drive down the road and find something to watch rather than streaming whatever we want whenever we want from the comfort of our beds? Why do we want fewer options?

That last one. That’s it. That’s what the itch is. Blockbuster nostalgia isn’t really about the VHS or the strip mall, the warm smell of the tape or the quiet in the room. It’s about a longing for limitation, our secret wish for less.

We have so many choices today, we don’t know what to pick. Decision paralysis. Some of us suffer from it terribly, some of us less so. But we’re all aware of the problem. We understand the term. We all know that it’s easier to pick from three than it is from three hundred.

The problem of decision paralysis isn’t limited to what we are going to watch some Thursday evening. We see the problem with young people and dating apps. There is a sense there is always another one waiting. There are infinite partners out there. Don’t settle down; there might be a better match. Always another match. No one can make the decision to just be happy and just get married.

I’ve seen it when someone has a bunch of money saved. Too much time and nothing to do. They talk about going here or there, doing this or trying that. They hem and haw about it for months, and then years. I ask them, “What are you waiting for?” They tell me, “I’m not sure it’s what I want to do.”

Aisle be seeing you

The world is our oyster. We can do anything we want, we are spoiled rotten, and we can’t make a choice. We should be happier than ever, but we aren’t. Not really. We secretly, deep down, wish something would just take away our choices and make it all simpler for us. We would complain about it, but we would secretly be thankful for it. We can’t really do it on our own. Limiting ourselves voluntarily never feels the same as having reality do it for us.

Our problems today are, in a way, pitiful. I know our ancestors would probably mock us for our so-called decision paralysis. But they didn’t know this world. They only know the limited world. Their struggles were often physical. Ours are psychological.

That’s why we miss Blockbuster, or at least what Blockbuster represents or reminds us of. Less. Limitation. The life where we can only do so much, or see so much, where our world is a little smaller and we, in turn, feel a little greater.

Back at Blockbuster we would meander through the aisles, looking at cover after cover, occasionally flipping one over to see what else the back might reveal. After a while, we would make our choice, pay the $1.99 at the glossy counter, take the movie home, make some popcorn on the stove, turn on the TV, pop in the tape, press play, and see if what we chose was any good.

We had fewer choices, and it was fine. Actually it was more than fine, it’s really what we want deep down, even if we don’t want to admit it. That’s why we kind of miss Blockbuster in a strange little way.

Athanasios Gioumpasis/Getty Images

Athanasios Gioumpasis/Getty Images

Bettman/Getty Images

Bettman/Getty Images

Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Universal History Archive/Getty Images Horst P. Horst/Condé Nast | Getty Images

Horst P. Horst/Condé Nast | Getty Images

Photo by Xavier ROSSI/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Photo by Xavier ROSSI/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images Image source: Pueblo County (Colorado) Sheriff's Office

Image source: Pueblo County (Colorado) Sheriff's Office