![]()

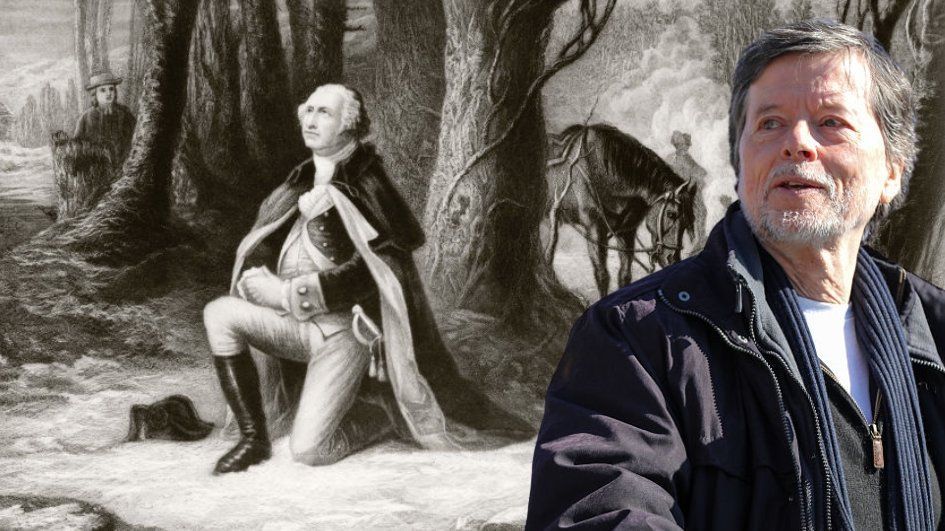

Ken Burns has built his career as America's memory keeper. For decades, he's positioned himself as the guardian against historical revisionism, the man who rescues truth from the dustbin of academic fashion. His camera doesn't just record past events — it sanctifies them.

For nearly five decades, Burns has reminded Americans that memory matters and that history shapes how a nation sees itself.

Jefferson's 'Nature’s God' wasn’t a placeholder. It was a real presence. He sliced up the Gospels but still bowed to the idea of eternal moral law.

Which makes his recent performance on Joe Rogan's podcast all the more stunning in its brazen historical malpractice.

At the 1-hour, 17-minute mark, Burns delivered his verdict on the Founding Fathers with the confidence of a man who's never been wrong about anything.

They were deists, he declared. Believers in a distant, disinterested God, a cosmic clockmaker who wound up the universe and wandered off to tend other galaxies. Cold, clinical, and entirely absent from human affairs.

It's a tidy narrative. One small problem: It's so very wrong.

The irony cuts so deep it draws blood. The man who made his reputation fighting historical revisionism has become its most prominent practitioner. Burns, the supposed guardian of American memory, has developed a curious case of selective amnesia, and Americans are supposed to pretend not to notice.

The deist delusion

Now, some might ask: Who cares? What difference does it make whether Washington believed in an active God or a divine absentee landlord? The answer is everything, and the fact that it's Burns making this claim makes it infinitely worse.

This isn't some graduate student getting his dissertation wrong. This is America's most trusted historical documentarian, the man whose work shapes how millions understand their past. When Burns speaks, the nation listens.

When he gets it wrong, the mistake seeps like an oil spill across the national story, quietly coating textbooks, classrooms, and documentaries for decades.

Burns is often treated as an apolitical narrator of history, but there’s a soft ideological current running through much of his work: reverence for progressive causes, selective moral framing, and a tendency to recast American complexity through a modern liberal lens.

Burns isn't stupid. One assumes he knows exactly what he's saying. If he doesn't — if his remarks on Rogan's podcast represent genuine ignorance rather than deliberate distortion — then we have serious questions about the depth of his actual knowledge. How does someone spend decades documenting American history while missing something this fundamental?

The truth is that Americans have been lied to about the Founders' faith for so long that Burns' deist mythology sounds plausible. The secular academy has been rewriting these men for decades, stripping away their religious convictions, sanding down their theological edges, making them safe for modern consumption. Burns isn't breaking new ground. He's perpetuating a familiar falsehood.

Taking a knee

Let's start with George Washington, the supposed deist in chief. Burns would have us believe the general bowed not to God, but to a kind of cosmic CEO who delegated all earthly duties to middle management. But at least one contemporary account attests that Washington knelt in the snow at Valley Forge — not once, but repeatedly.

He called for the national day of "prayer and thanksgiving" that eventually became the November federal holiday we know today. He invoked divine Providence so frequently you’d think he was writing sermons, not military orders.

His Farewell Address reads more like a theological tract than a retirement speech, warning that “religion and morality are indispensable supports” of political prosperity. Does that sound like a man who thought God had checked out?

John Adams, another Founder often branded a deist, wrote bluntly that “our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people.”

Adams saw the American Revolution as the outgrowth of divine intervention. As he wrote to Thomas Jefferson in 1813, “The general principles on which the fathers achieved independence were ... the general principles of Christianity.”

And what of Jefferson? By far the most heterodox, even he never denied divine order. His “Nature’s God” wasn’t a placeholder. It was a real presence. He sliced up the Gospels but still bowed to the idea of eternal moral law. Whatever his quarrels with organized religion, he did not believe in a silent universe.

Some of these men were, philosophically at least, frustrated Catholics. They couldn’t fully accept Protestantism, but they had no access to the Church’s intellectual infrastructure. The natural law reasoning that permeates their political thought — Jefferson’s “self-evident truths,” Madison’s checks and balances born of man’s fallen nature — comes straight from Aquinas, filtered through Locke, Montesquieu, and centuries of Christian jurisprudence.

The Founders weren’t Enlightenment nihilists. They weren’t secular technocrats. And they certainly weren’t deists. They were men steeped in a moral framework older than the American experiment itself.

Burns, for all his sepia-toned genius, has a blind spot you could drive a colonial wagon through. His documentaries glow with progressive reverence — plenty of civil rights and moral reckoning, but the Almighty gets the silent treatment. God may have guided the Founders, but in Ken’s cut, he barely makes the final edit.

The sacred and the sanitized

I mentioned irony at the start, but it deserves more than a passing nod. That's because the septuagenarian's own cinematic legacy contradicts the very theology he now peddles on podcasts.

His brilliant nine-part series "The Civil War" captured the moral agony of a nation tearing itself apart, and it did so in unmistakably religious terms. Here Burns treats Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address — haunted, prophetic, bathed in biblical cadence — with reverence, not revisionism.

The series understood something essential: Americans have always been a biblical people. They see their history not just in terms of dates and treaties, but in terms of sin, sacrifice, and redemption. Sacred story, divine purpose — this was the language of American reckoning.

The Founders weren’t saints, and they weren’t simple. They read Greek, spoke Latin, studied Scripture, and debated philosophy with a seriousness that puts modern politicians to shame. But they weren’t spiritual agnostics, either.

They were men of imperfect but active faith, shaped by the Bible, steeped in Christian moral tradition, and convinced that human rights came not from government but from God.

They didn’t build a republic of personal preference. They built one grounded in enduring truths that predated the Constitution, anchored to the idea that law and liberty meant nothing without a higher law above them.

Burns may deal in memory, but his treatment of religion reveals something else entirely. He doesn’t misremember. He reorders. He filters faith through a modern lens until it becomes unrecognizable.

Memory isn’t just about what’s preserved — it’s about what’s permitted. And when the sacred gets cast aside, what’s left isn’t history. It’s propaganda with better lighting.

If Americans are taught by foreigners (and their children) to hate the men and ideals that birthed liberty, they will never fight to protect it when the next settler immigrant tries to take it away.

If Americans are taught by foreigners (and their children) to hate the men and ideals that birthed liberty, they will never fight to protect it when the next settler immigrant tries to take it away. Whether through Supreme Court precedent, statutes, or even constitutional amendments, ours is a parental rights moment that demands action to allow parents the right to do their duty and raise their children.

Whether through Supreme Court precedent, statutes, or even constitutional amendments, ours is a parental rights moment that demands action to allow parents the right to do their duty and raise their children.

Wynnter via iStock/Getty Images

Wynnter via iStock/Getty Images

Ryan brought DEI to the university in ways never seen before, capitulating to Black Lives Matter dishonesty and bending the knee to race-baiting social justice combatants.

Ryan brought DEI to the university in ways never seen before, capitulating to Black Lives Matter dishonesty and bending the knee to race-baiting social justice combatants.

Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images Last week, unelected District Court Judge Brian Murphy told the Trump administration that it must bring back an illegal alien who was deported because, according to Murphy, the alien needs due process — and the Trump administration buckled. In court filings on Wednesday, the Department of Justice (DOJ) said it would bring back the illegal […]

Last week, unelected District Court Judge Brian Murphy told the Trump administration that it must bring back an illegal alien who was deported because, according to Murphy, the alien needs due process — and the Trump administration buckled. In court filings on Wednesday, the Department of Justice (DOJ) said it would bring back the illegal […]

sesame via iStock/Getty Images

sesame via iStock/Getty Images