![]()

The most striking images from the recent anti-Immigration and Customs Enforcement riots in Los Angeles depicted protesters defiantly waving the Mexican flag. Some commentators noted the irony: Why carry the flag of the very country you don’t want to be deported to? Others offered a darker interpretation — the flag wasn’t just a symbol of heritage but a claim. The message: California rightfully belongs to Mexico.

That sentiment echoes the increasingly common ritual of “land acknowledgements” on college campuses. Event organizers now routinely recite statements recognizing that a school sits on land once claimed by this or that Indian tribe. But such cheap virtue signaling skips over a key point: Tribes seized land from each other long before Europeans arrived.

The United States had offered to purchase the disputed territories. Mexico treated the offer as an insult and indignantly refused. And the war came.

Do the descendants of the Aztecs have a claim to California and the rest of the American Southwest? The answer is a simple and emphatic no. The United States holds that territory by treaty, by financial compensation, and, yes, by conquest. But the full story is worth examining — because it explains why Spain and later Mexico failed to hold what the United States would eventually claim.

The rise and fall of the Spanish empire

Spain launched its exploration and conquest of the Americas in the 15th century and eventually defeated the Aztec empire in Mexico. But by the 18th century, Spanish control began to wane. The empire’s model of rule — exploitative, inefficient, and layered with class resentment — proved unsustainable.

At the top were the peninsulares, Spaniards born in Europe who ran colonial affairs from Havana and Mexico City. They had little connection to the land or the people they governed — and often returned to Spain when their service ended.

Below them stood the creoles, locally born Spaniards who could rise in power but never fully displace the peninsulares.

Then came the mestizos — mixed-race descendants of Spaniards and natives — and, finally, the native peoples themselves, descendants of the once-dominant Aztecs, who lived in state of peonage.

Inspired by the American Revolution, Mexico declared itself a republic in 1824. But it lacked the civic traditions and institutional structure to sustain self-government. Political chaos followed. Factionalism gave way to the dictatorship of Antonio López de Santa Anna, who brutally suppressed a rebellion in Coahuila y Tejas.

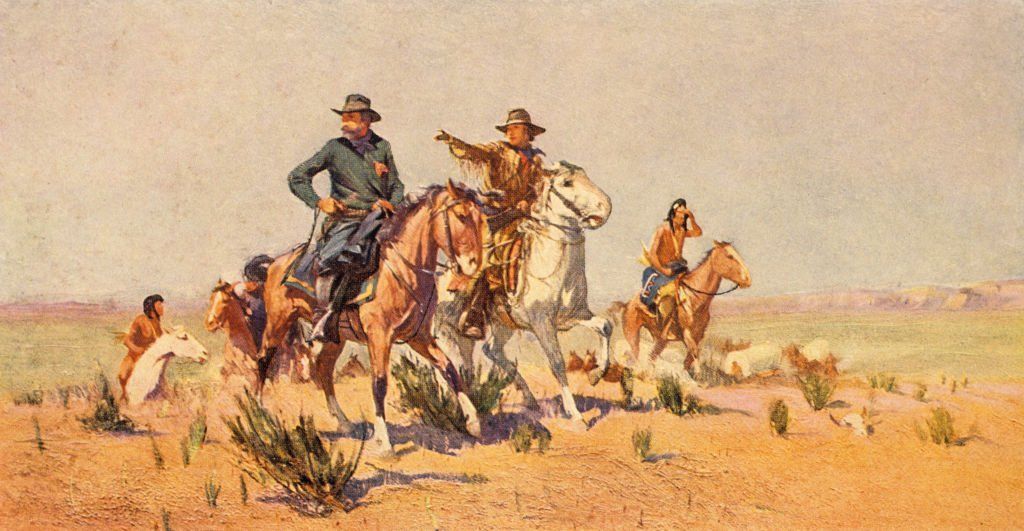

Texas had long been a trouble spot. Even before independence from Spain, Mexican officials encouraged American settlement to create a buffer against Comanche raids. The Comanche — superb horsemen — dominated the Southern Plains, displacing rival tribes and launching deep raids into Mexican territory. During the “Comanche moon,” their war parties could cover 70 miles in a day. They were a geopolitical power unto themselves.

RELATED: Flipping cars for ‘justice’ — then back to poli-sci class

![]() Photo by: Prisma/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Photo by: Prisma/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

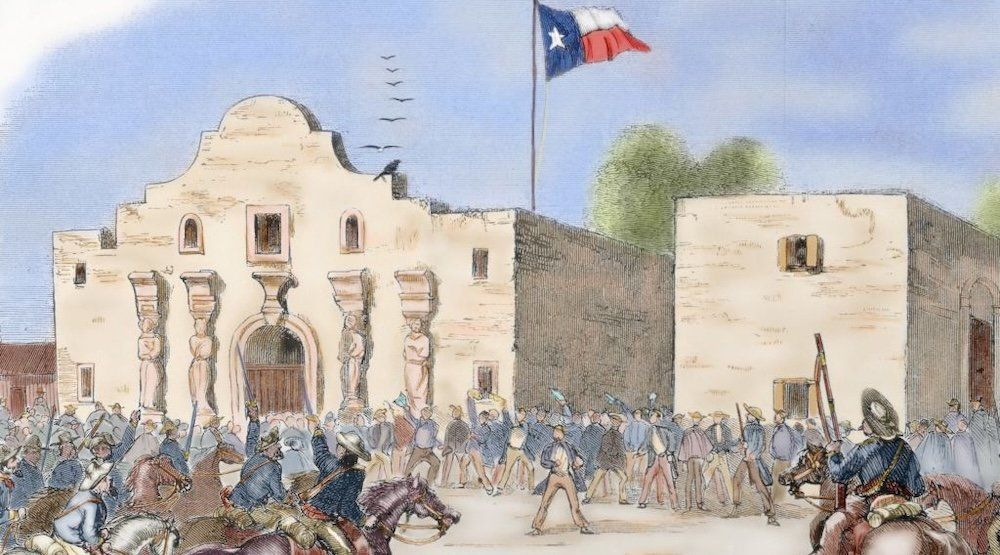

Anglo settlers in Texas brought their own ideas of decentralized government. When tensions escalated, they declared independence. Santa Anna responded with massacres at Goliad and the Alamo. But after his defeat and capture at San Jacinto, he granted Texas independence in exchange for his life. Mexico’s government refused to honor the deal — and continued to claim Texas, insisting that the border lay at the Nueces River, not the Rio Grande.

How the Southwest was won

After the United States annexed Texas in 1845, conflict became inevitable. Mexican forces crossed the Rio Grande and clashed with U.S. troops. President James Polk requested a declaration of war in 1846.

The Mexican-American War remains one of the most decisive — and underappreciated — conflicts in U.S. history. The small but capable U.S. Army, bolstered by state volunteers, outclassed Mexican forces at every turn. American troops seized Santa Fe and Los Angeles.

General Zachary Taylor pushed south, winning battles at Resaca de la Palma and Monterrey. General Winfield Scott launched a bold amphibious assault at Veracruz, then cut inland — without supply lines — to capture Mexico City. The Duke of Wellington called the campaign “unsurpassed in military annals.”

The war served as a proving ground for a generation of officers who would later lead armies in the Civil War.

Diplomatically, the war might have been avoided. The United States had offered to purchase the disputed territories. Mexico treated the offer as an insult and indignantly refused. And the war came.

Territory bought and paid for

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, ended the conflict. Mexico ceded California and a vast swath of land that now includes Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Wyoming. Mexico also gave up its claim to Texas and accepted the Rio Grande as the southern border.

In return, the United States paid Mexico $15 million “in consideration of the extension acquired by the boundaries of the United States” and assumed certain debts owed to American citizens. Mexicans living in the newly acquired territory could either relocate within Mexico’s new borders or become U.S. citizens with full civil rights. The Gadsden Purchase added even more land.

The United States gained enormously from the war at the expense of Mexico. Critics of the expansionist policy known as “manifest destiny,” including the Whigs and Ulysses S. Grant, called the result unjust. Some Southerners wanted to annex all of Mexico to expand slavery. That plan was wisely rejected, though the “law of conquest” made it a possibility.

Still, the U.S. paid for the land, offered citizenship to the inhabitants, and declined to claim more than necessary. In the rough world of 19th-century geopolitics, that counted as a just outcome.

Photo by: Prisma/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Photo by: Prisma/Universal Images Group via Getty Images With a pro-family agenda that benefits not only black Americans but all Americans, Trump can usher in a historic shift that is long overdue.

With a pro-family agenda that benefits not only black Americans but all Americans, Trump can usher in a historic shift that is long overdue. The story of the Comanches and the Red River War, whose 150th anniversary we mark this year, shows the absurdity of the 'noble savage' narrative.

The story of the Comanches and the Red River War, whose 150th anniversary we mark this year, shows the absurdity of the 'noble savage' narrative. The Ukraine war is dragging on with no strategy to end it in sight — it's exactly the kind of conflict American leaders who have fought and won wars would disapprove of.

The Ukraine war is dragging on with no strategy to end it in sight — it's exactly the kind of conflict American leaders who have fought and won wars would disapprove of. Liz Cheney and Colin Kaepernick lost their jobs for the same reason: They were incapable of doing what they were hired to do.

Liz Cheney and Colin Kaepernick lost their jobs for the same reason: They were incapable of doing what they were hired to do.