John J. Pinder Jr.: Baseball hero who chose greater sacrifice

By March 1944, Army Tech. 5th Grade John J. Pinder Jr. had seen over a year of combat. With the 16th Infantry, he'd participated in the Allied landings at Algeria and fought in in the mountains of Sicily. Now, he was in England, preparing for the planned invasion of Normandy.

And yet, it was his family's well-being, not his own, that concerned him. His younger brother Harold, a bomber pilot in the Army Air Corps, had been shot down over Europe that January. Having managed to the get the details of his brother's disappearance, as well as his probable whereabouts in a German POW camp, Pinder wrote his father a nine-page letter sharing everything he knew.

He concluded it by encouraging his father to hope for the best while implying that he would help him handle the worst:

"You and I must go on trusting that 'the kid' is okay. As soon as I hear anything whatsoever, I'll let you know at once. You do the same for me, Remember there has never been anything but complete truth between all three of us boys."

The boys (they also had a younger sister, Martha) grew up in McKee's Landing, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Pittsburgh. John played sandlot baseball and soon developed a fearsome reputation on the mound; his curve ball was especially deadly. He bounced around the minors for a few years, where he impressed fans and teammates with his determination, work ethic, and talent. They seemed to herald a great big-league career. These dreams were put on hold when Pinder entered the Army in January 1942.

On the morning of June 6, 1944, Pinder and the 16th Infantry were the first to storm Omaha beach. Shrapnel from an artillery shell ripped through their transport when it was still 100 yards off shore, killing some men instantly and leaving the rest to wade through waist-deep water while being strafed with machine gun fire.

For Pinder, the going was particularly tough. He carried the radio equipment necessary to establish communication between the Navy gunners and the men on the beach — bulky gear that weighed some 80 pounds. As Pinder made his way to shore, bullets ripped through the left side of his face; he held his cheek together and kept moving forward.

Twice he ran back into the surf to gather more crucial equipment; on the second trip, machine gun fire ripped through his side, but he somehow kept going. He was helping set up the equipment when he passed out from blood loss. He died hours later; it was his 32nd birthday.

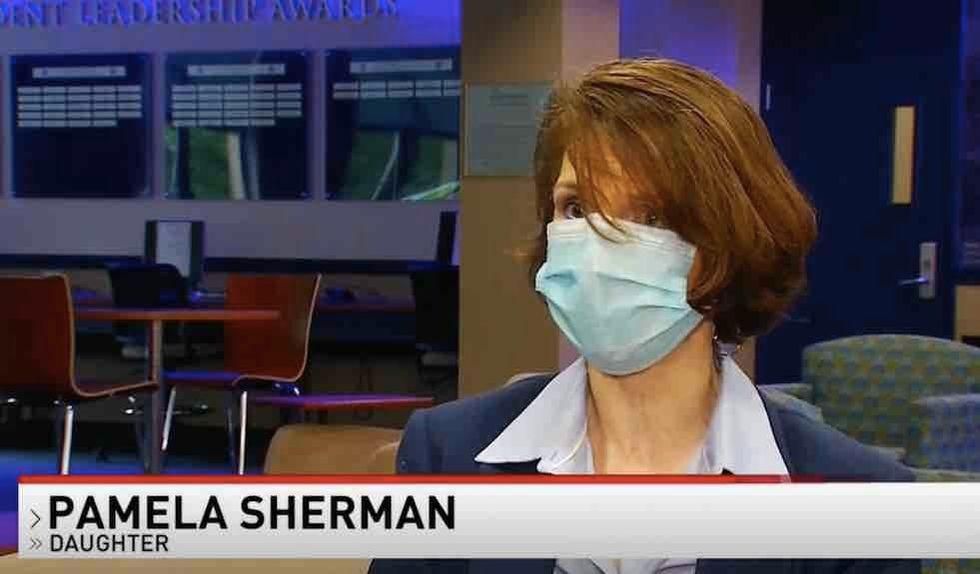

His brother Harold learned of the death while still in the German prison camp. When the war ended, he was released and went home, living until 2008.

Pinder was one of 12 soldiers to receive the Medal of Honor for valor on D-Day; all but four received the award posthumously. Pinder's father accepted the award on his son's behalf on January 26, 1945.

Image source: WJAR-TV video screenshot

Image source: WJAR-TV video screenshot Image source: WJAR-TV video screenshot

Image source: WJAR-TV video screenshot Image source: WJAR-TV video screenshot

Image source: WJAR-TV video screenshot Image source: WJAR-TV video screenshot

Image source: WJAR-TV video screenshot Image source: WJAR-TV video screenshot

Image source: WJAR-TV video screenshot Image source: WJAR-TV video screenshot

Image source: WJAR-TV video screenshot Image source: WJAR-TV video screenshot

Image source: WJAR-TV video screenshot

SHOCKING Hitler and FDR History Revealed | @studoesamerica