‘Ungrateful Piece Of Sh*t’: Kara Swisher Berates Californians Fleeing New Wealth Tax

'We deserve the taxes from you'

In a move championed by President Donald Trump, the Federal Reserve cut its key interest rate by 0.25% to a range of 3.5% to 3.75% on Wednesday, the third cut this year, lowering borrowing costs and giving some lift to a flagging job market.

Only three members of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors voted against the cut: Stephen Miran, who wanted to lower the target range for the federal funds rate by 0.5%, and Austan Goolsbee and Jeffrey Schmid, who both figured it was presently best not to have any cuts at all.

'Available indicators suggest that economic activity has been expanding at a moderate pace.'

Joseph Brusuelas, chief economist for the financial services firm RSM US, noted in a Tuesday analysis that the Fed was faced with the "difficult choice of either aggressively fighting inflation or hoping to revive a sluggish labor market and slowing economic activity when it meets on Tuesday and Wednesday."

Rate cuts can help boost the stock market — encouraging spending, investing, and business activity by lowering savings rate and borrowing costs. However, by increasing the supply of money, they can also exacerbate inflation.

The annual inflation rate was around 3% for the 12 months ending September, according to U.S. Labor Department data. The Fed's inflation target is 2% over the longer run — hence the resistance to another cut by some policymakers.

"The [Federal Open Market Committee] seeks to achieve maximum employment and inflation at the rate of 2 percent over the longer run. Uncertainty about the economic outlook remains elevated," the Fed said in a statement on Wednesday. "The Committee is attentive to the risks to both sides of its dual mandate and judges that downside risks to employment rose in recent months."

In light of its goals and "the shift in the balance of risks," the FOMC determined that a drop in the rate by 0.25% was worthwhile.

"Available indicators suggest that economic activity has been expanding at a moderate pace. Job gains have slowed this year, and the unemployment rate has edged up through September," the Fed noted further. "Inflation has moved up since earlier in the year and remains somewhat elevated."

The rate-cut decision on Wednesday comes months after the Fed similarly lowered its benchmark interest rate by 25 basis points in September to a range of 4% to 4.25%, and after weeks of disagreement on the central bank's 12-member policy committee regarding the prudent way forward.

Chris Brigati, chief investment officer at the financial services company SWBC, told the Financial Post ahead of the announcement that the Federal Reserve was divided on how to proceed with rate cuts in 2026 "given the delicate balance between job market weakness and still-elevated inflation."

"There is also uncertainty about the new Fed chair, and that may also add to the central bank's reluctance to make any major rate moves in the months leading up to Chair Powell's term ending," Brigati added.

In search of someone suitable to replace Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, whose term ends in May, the president has been interviewing various candidates, including Christopher Waller and Michelle Bowman, both members of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors; former Fed governor Kevin Warsh; and BlackRock fixed-income chief Rick Rieder. Top White House economic adviser Kevin Hassett is, however, reportedly regarded as the frontrunner.

The president told reporters on Air Force One on Tuesday, "We're going to be looking at a couple of different people, but I have a pretty good idea who I want."

When asked in his interview with Politico the previous day whether it is "a litmus test that the new chair lower interest rates immediately," Trump said yes and noted, "We're fighting through interest rates."

The Federal Reserve also released on Wednesday its regional bank presidents and governors' quarterly set of economic projections. They anticipate a rise in the unemployment rate from 4.4% in September to 4.5% by year's end; the GDP to grow by 2.3% in 2026; and inflation to sink, but nowhere below their 2% target.

Like Blaze News? Bypass the censors, sign up for our newsletters, and get stories like this direct to your inbox. Sign up here!

Chick-fil-A was once again ranked as the number-one fast-food restaurant in the American Customer Satisfaction Index. It’s the 11th consecutive year the chicken chain has held the top spot.

But it's not just CFA's food and service that have made it one of the most popular chains in America. It’s something much more nuanced.

Chick-fil-A didn’t set out with a customer-first strategy and later decide to care about people.

Unlike most other organizations in the industry, Chick-fil-A has discovered an authentic way to integrate business strategy and corporate culture. It’s often said that “culture eats strategy for breakfast.” I’ve found that this statement is only half true. Culture is undoubtedly powerful. It shapes mindsets, decisions, and environments. However, it doesn’t negate the need for strategy.

For true, lasting success, culture and strategy need to feed off each other. When they’re disconnected, the result is often imbalance, misalignment, and, ultimately, mission drift. A business can be healthy yet lack purpose, or have a clear purpose yet operate in an unhealthy way.

Thriving organizations — the ones that stand the test of time — are those that harmonize who they are (their culture) with what they do and how they do it (their strategy). This integration is essential for missionally driven leadership.

Let’s go back to Chick-fil-A.

The company is built on biblical values, honors the Sabbath, fosters servant-hearted leadership, and champions hospitality. These values are operational standards. They guide how team members respond to guests with “my pleasure,” how conflict is resolved, and even how franchise partners are selected.

Chick-fil-A didn’t set out with a customer-first strategy and later decide to care about people. It cared about people first, and from that foundation, the strategy naturally emerged. That distinction matters.

RELATED: Here are 5 Christian companies that join Chick-fil-A in publicly proclaiming their Bible-based views

When core values shape strategic direction, execution becomes more consistent and more resilient, especially in the face of disruption.

And yet culture alone is not enough. Without strategy, culture easily becomes sentimental, a fond memory of “how things used to be” without the structure needed to drive meaningful outcomes. Leaders must be vigilant in asking: Is our culture shaping what we pursue, how we define success, and how we evolve in the face of change?

The return-to-office debate provides a timely example of how strategy and culture must interact.

In June 2025, Ford Motor Company announced it would require white-collar employees to return to the office four days per week. CEO Jim Farley framed the decision as a step toward a “more dynamic company,” one that fosters in-person creativity and collaboration. That’s a strategic choice, but one rooted in a specific cultural aspiration.

Across industries, leaders are weighing similar decisions. Do we bring everyone back? Stay remote? Create a hybrid solution?

While there’s no one-size-fits-all answer, the wrong approach is to follow trends blindly or make decisions out of fear. The right starting point is culture. What kind of culture are we trying to build? What rhythms cultivate collaboration and mentorship? Do our physical and digital environments reinforce the values we profess or erode them?

For some organizations, RTO policies can rekindle a sense of belonging and a shared mission. For others, flexibility and trust are core values best expressed through remote autonomy. The key is less about whether employees sit at a shared desk and more about whether the strategy supports the cultivation of a shared identity.

In my work with CEOs and business owners, I’ve witnessed a key dynamic among healthy organizations: They let culture shape strategy, and they let strategy reinforce culture. It’s a two-way street.

Right now, culture matters more than ever in attracting and retaining talent, sparking innovation, and uniting multigenerational teams around a shared purpose. That’s why everything from hiring practices and customer service to key performance indicators and product development must reflect and reinforce the values a company holds dear.

It’s one thing to say we value integrity; it’s another to weave it into how we sell, serve, and lead.

So what does this look like in practice?

First, leaders must examine whether their strategic priorities truly align with the values they profess. If your organization touts that people matter most, does your strategy show it through investments in employee development, customer care, and sustainable work rhythms?

Next, consider what kind of culture your current strategy is creating, whether intentional or not. Every strategy has cultural side effects. Sometimes, a relentless drive for performance without margin produces a culture of fear and burnout.

Then, consider your internal language. Do your people have a shared understanding of what terms like “excellence,” “service,” or “innovation” mean within your unique context? Without clarity, even good intentions can lead to confusion or misalignment.

Finally, reflect on leadership behavior. Are you and your leaders embodying both the values and the strategic vision? Employees learn far more from what their leaders model than what they say. When leaders walk in alignment with both strategy and culture, they build trust, and trust builds momentum.

So yes, culture may eat strategy for breakfast, but only when the two sit at the same table, aligned, accountable, and advancing together.

The real secret behind Chick-fil-A's dominance? Culture and strategy are on the same menu.

One of the least understood but most consequential aspects of American government is the United States Federal Reserve System. Bankers, investors, and even the president sit with bated breath, waiting to see how the Fed will manage interest rates.

The Fed is so important to the world economy that the president sometimes may feel the need to voice his administration’s position and hope the chairman of the Federal Reserve will acquiesce to his wishes. Sometimes, however, he may point out issues with the chairman’s performance, puncturing the claim of central bank independence. President Donald Trump recently accused Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell of being too late with interest rate cuts “except when it came to the Election period when he lowered [interest rates] in order to help Sleepy Joe Biden, later Kamala, get elected.”

Powell was clearly willing to play political games that cost Americans their businesses and their ability to feed their children.

Americans had suffered through continued elevated inflation, in part, because Jerome Powell wanted to keep his job.

With the president’s attempted firing of Fed Governor Lisa Cook, Powell has jockeyed himself a position as the white knight of central bank independence. He alleges that tariffs, which have no connection with monetary policy on their own, are the cause of an increase in inflation. He seems intent on keeping interest rates high.

Whether that is a good decision is a different subject altogether (the Mises Institute’s Ryan McMaken takes on that idea). But what is clear is that Jerome Powell is not the principled opponent to Trump he claims to be; he is just as much a political actor as the president and Congress.

Powell’s politicization is clear in how the Fed functions today. Economists and political scientists stress the importance of central bank independence as a hedge against what is called “political business cycles.” These cycles occur when monetary authorities pump the economy full of easy money to suppress employment problems and create an illusion of prosperity. This eventually results in higher inflation. Politicians reap the benefits of this illusion and blame inflation on something else: energy shocks, supply shocks, disasters, tariffs, etc.

The root of the problem is when new money is created to push down interest rates. Politicians who have control over the monetary authorities are incentivized to push for easier monetary policy to relieve unemployment in the face of elections. If they lose, their opponents reap the consequences; if they win, rates might be allowed to rise to fight inflation, and the illusion is dispelled.

By insulating the central bank from political pressure, the Fed is supposed to be able to pursue its mandates such as low and stable inflation or low unemployment. While this appears sound at first glance, reality shows that the Federal Reserve has never truly been independent.

The crowning moment that defines U.S. central bank independence is the Treasury-Fed Accord of 1951, which severed the support the Fed had given the Treasury Department in financing World War II and the Marshall Plan. But as Jonathan Newman has uncovered, this accord was a declaration of independence in name only.

The chairman of the board of governors, Thomas McCabe, by all accounts did appear to favor the separation of the Federal Reserve’s functions from that of the Treasury’s. Yet McCabe was not present at the Accord meetings. Moreover, McCabe resigned in protest soon after they concluded.

Treasury stooge William McChesney Martin Jr. was then appointed Fed chairman. Martin paid lip service to the idea of an independent Fed but ultimately revealed his cooperation with the Treasury Department in a 1955 interview. President Kennedy even renominated him for having “cooperated effectively in the economic policies of [his] administration.”

The Treasury and the Fed have had a revolving door ever since. Martin had chaired the Export-Import Bank in addition to serving as assistant treasury secretary. G. William Miller left his role as Fed chairman to serve as the secretary of the treasury. Paul Volcker served in Nixon’s Treasury Department before joining the Fed.

Particularly egregious was Janet Yellen, who served on President Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers and then was appointed to the Federal Reserve by both Clinton and later President Barack Obama. She ultimately would become secretary of the treasury under President Joe Biden. Even Jerome Powell served in President George H.W. Bush’s Treasury Department before returning to the private sector. Barack Obama appointed Powell to the Federal Reserve Board, and President Trump later nominated him as Fed chairman.

The constant revolving door between the CEA, the Treasury Department, and the Federal Reserve is no different from agencies like the Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Disease Control, and Department of Energy. It reeks of corruption and political influence and certainly proves the Federal Reserve is not truly independent.

Examining Jerome Powell’s own actions when his job was on the line shatters the illusion of so-called central bank independence.

In 2021, as inflation began to climb, Powell dubbed the phenomenon “transitory.” The Biden administration had just taken office a few months prior, and rampant inflation was likely to stick around for the midterm elections. Thus, blame had to be cast elsewhere. It’s also noteworthy that Powell’s four-year term was set to expire in 2022. If you are up for a performance review, you might choose to kiss up to your boss so that you aren’t fired. Central bankers are no different.

Inflation continued to rise through November, climbing to 7% year over year. Americans demanding relief could not turn to Jerome Powell, who kept the Federal Funds Rate at 0%, attempting to hide the real state of the economy for Biden, who renominated him that same month. It was only then that Powell dropped the term “transitory” to describe inflation.

The first rate hike of 0.5% happened in May 2022, after the Senate Banking Committee had advanced Powell’s nomination. Soon after, with rates still low, Powell was confirmed by a Democrat-controlled Senate. Only two months after his confirmation, the Fed finally began to hike interest rates at historic speed. Inflation had peaked in June at 9% year over year. Americans had suffered through continued elevated inflation, in part, because Jerome Powell wanted to keep his job.

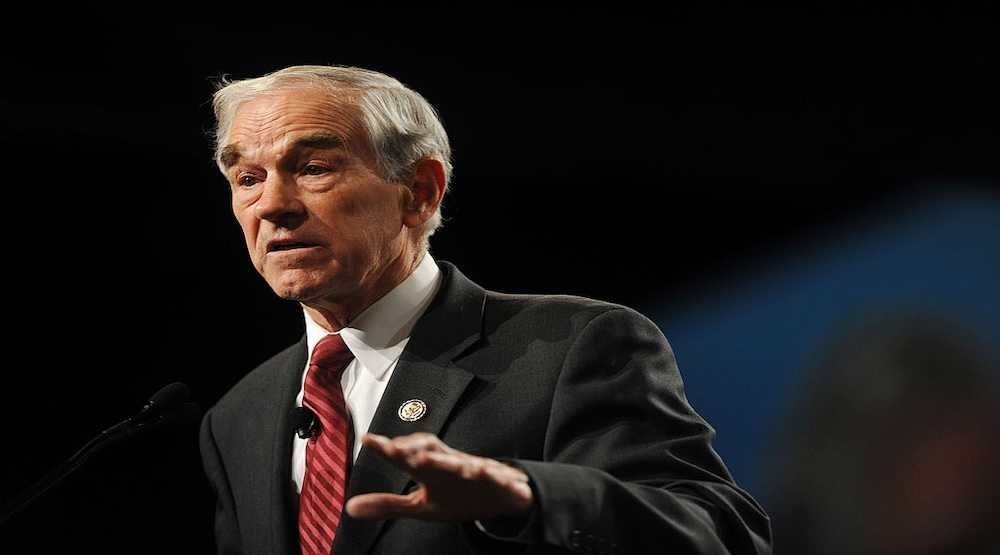

RELATED: Ron Paul exposes how the Federal Reserve keeps up its scam

A Fed that was hawkish on inflation would have raised interest rates higher and faster than Powell did, not allowing inflation to run rampant. Powell was clearly willing to play political games that cost Americans their businesses and their ability to feed their children.

The Fed has never been independent — it has always been political. Economists would do well to admit this and argue their case rather than pussyfoot around the question of what interest rates should be or if interest rates should be set at all.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published at the American Mind.